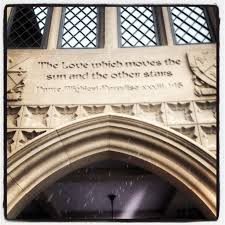

On the west side of the stone entryway to the beautiful humanities center on my campus, in only its fourth year of operation, is carved a memorable saying from the Gospel of John: You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free. On the top of the opposite east side of the entryway is the equally memorable closing line from Paridiso, the final book of Dante’s The Divine Comedy:

On the west side of the stone entryway to the beautiful humanities center on my campus, in only its fourth year of operation, is carved a memorable saying from the Gospel of John: You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free. On the top of the opposite east side of the entryway is the equally memorable closing line from Paridiso, the final book of Dante’s The Divine Comedy:  The Love which moves the sun and the other stars. In my estimation the choice of this passage for such an exalted position on the building is controversial; when the building was still in the planning stage, I made the tongue-in-cheek argument that nothing more appropriate could be inscribed on the front of a classroom building than what is written over the gates of Hell in Canto III of Inferno, the first book in Dante’s masterwork: Abandon hope, all ye who enter here. But I lost the argument and had to settle for printing that line off and taping it on my office door. It must have worked, because very few students come to visit me in my office.

The Love which moves the sun and the other stars. In my estimation the choice of this passage for such an exalted position on the building is controversial; when the building was still in the planning stage, I made the tongue-in-cheek argument that nothing more appropriate could be inscribed on the front of a classroom building than what is written over the gates of Hell in Canto III of Inferno, the first book in Dante’s masterwork: Abandon hope, all ye who enter here. But I lost the argument and had to settle for printing that line off and taping it on my office door. It must have worked, because very few students come to visit me in my office.

Dante’s vision at the end of Paridiso is the climax of an agonizing journey through Hell, then Purgatory, and finally Heaven. This capstone experience, strangely enough for a guy who is never at a loss for words, is one that he struggles mightily to convey.  One gets the impression that words fail him and his linear thought process is dissolved as he is subsumed into his long-awaited encounter with the Divine. But I’ve never found Dante’s vision compelling, simply because it’s just that. A vision. And it’s so Catholic, with multitudes of saints, angels, and Mary swirling around in a choreographed dance. I actually resonate more fully with Dante and his guide Virgil as they pick their way through the horrors of Hell and the trials of Purgatory—these portions of the journey I can resonate with because they remind me of the world I actually live in with all of its contradictory beauty and ugliness. That’s the world in which I will be embedded this coming semester that begins in two weeks with a bunch of sophomore students as we explore grace, truth and freedom in the Nazi era, finding glimmers of hope and nuggets of wisdom in the middle of the worst that humanity can devise.

One gets the impression that words fail him and his linear thought process is dissolved as he is subsumed into his long-awaited encounter with the Divine. But I’ve never found Dante’s vision compelling, simply because it’s just that. A vision. And it’s so Catholic, with multitudes of saints, angels, and Mary swirling around in a choreographed dance. I actually resonate more fully with Dante and his guide Virgil as they pick their way through the horrors of Hell and the trials of Purgatory—these portions of the journey I can resonate with because they remind me of the world I actually live in with all of its contradictory beauty and ugliness. That’s the world in which I will be embedded this coming semester that begins in two weeks with a bunch of sophomore students as we explore grace, truth and freedom in the Nazi era, finding glimmers of hope and nuggets of wisdom in the middle of the worst that humanity can devise.

We will spend some of the semester with Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German Protestant pastor and theologian who, imprisoned in Berlin’s Tegel Prison for more than a year because of his involvement in a failed attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler, found himself in his isolation fending off despair and realizing that whatever God is, God is none of the things he had always thought and taught. In letters to his best friend Eberhard Bethge, Bonhoeffer put his fears, his concerns, his hopes, and his life itself on display in language that is shocking and disturbing in its directness. We will consider two passage in a letter from Bonhoeffer to Bethge both in class and in on-line discussion forums  .

.

What is bothering me incessantly is the question of what Christianity really is, or indeed who Christ really is, for us today. The time when people could be told everything by means of words, whether theological or pious, is over, and so is the time of inwardness and conscience—and that means the time of religion in general.

Later in the letter, he repeats that “the time of Christianity is over.” Students in past versions of this course have been shocked that a Protestant pastor could write such a thing. But Bonhoeffer’s point is that none of the old formulas or descriptions work anymore, not in a world in which millions of human beings are disappearing as smoke and ashes from death camp chimneys. In a second letter a few weeks later to Bethge, Bonhoeffer continues the theme.

So our coming of age leads us to a true recognition of our situation before God. God would have us know that we must live as people who manage our lives without God. The God who is with us is the God who forsakes us. The God who lets us live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually.

God wants us to live in the world as if God does not exist, Bonhoeffer writes. What can this possibly mean? Once a student commented in our discussion forum how sad it was that Bonhoeffer had lost his faith. To which I replied, “This is not a man who has lost his faith.  This is a man for whom faith has come to mean something entirely different from what you are accustomed to.”

This is a man for whom faith has come to mean something entirely different from what you are accustomed to.”

A few short months after he wrote this letter, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed in Flossenburg Prison, just a handful of weeks before Germany surrendered to the Allies. Far from losing his faith, Bonhoeffer exemplifies a willingness to let faith evolve rather than crumble in the face of the greatest and most intense challenges. Shortly before his death he wrote a poem entitled “Who Am I?” in his notebook which ends in a place that provides hope for all persons of faith.

Weary and empty at praying, at thinking, at making,

Faint, and ready to say farewell to it all. . . .

Who am I? They mock me, these lonely questions of mine.

Whoever I am, you know, O God, I am yours!

Not long ago as I was driving to the 8:00 early show at church I caught a few minutes of Krista Tippett’s show “On Being” on NPR. Her guest was Margaret Wertheim, a physicist described in the promo as “a passionate translator of the beauty and relevance of scientific questions.”

http://onbeing.org/program/margaretwertheim-the-grandeur-and-limits-of-science/7472

Toward the end of the conversation Tippett notes that Wertheim, who was raised Catholic, has been described in the media as an atheist. “Are you an atheist?” Tippett asked.  Wertheim’s response brings us full circle back to Dante.

Wertheim’s response brings us full circle back to Dante.

I’d like to put it this way: I don’t know that I believe in the existence of God in the Catholic sense. But my favorite book is the Divine Comedy. And at the end of the Divine Comedy, Dante pierces the skin of the universe and comes face to face with the love that moves the sun and the other stars. I believe that there is a love that moves the sun and the other stars. I believe in Dante’s vision. And so, in some sense, perhaps I could be said to believe in God. And I think part of the problem with the concept of, “Are you an atheist or not?” is that our conception of what divinity means has become so trivialized and banal that I think it’s almost impossible to answer the question without dogma.

I love Wertheim’s answer because it is infused with Bonhoeffer’s energy. Dogmas and religious formulas will always fail because God is bigger than that. Seeking the love that moves the sun and the other stars will always take us to places we do not expect, places of beauty and darkness, a search energized by a faith that cannot be lost.