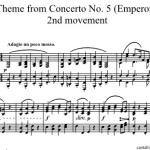

Midterm grades are due on my campus by midnight Wednesday; last Wednesday was the official midpoint of the semester. In my “Faith and Doubt” colloquium, we are starting two weeks on the work of Simone Weil after spending the first half of the semester, in order of appearance, with Anne Lamott, Job, Michel de Montaigne, Soren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, with Ludwig van Beethoven thrown in for musical relief four weeks or so ago.

Although they have been game and have (usually) met the high bar set by their professors, it is clear that the journey so far has been a challenging and heavy slog for the students. But what did they expect at 8:30 in the morning from a colloquium called “Faith and Doubt” co-taught by a philosopher and a political scientist who is also a Dominican Catholic priest? It’s one of the most intense courses I’ve ever been involved with, even though the authors I am responsible for working into the syllabus are ones whom I have taught many times over the years.

But I’ve never taught them together in one course with this unifying thread. It is turning out to be a Master Class in how to subject one’s faith to the acid test of reality—for me. And that makes sense. One of my mentors in my early years of teaching often said, only half-joking, that what we do in the classroom is for the professors more than the students—we just need the students there to pay for what we are doing.

Last week’s work on Dietrich Bonhoeffer brought the text of the previous authors considered into vivid focus. There is nothing more likely to put all of a person’s assumptions and expectations at risk than seeing them all fall apart and become irrelevant in the face of pressing current events. Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran pastor and theologian from a conservative, stable, and privileged family background, concluded that the rising totalitarian power of Hitler and Nazi party could not be addressed within the theological and academic framework with which he had been raised in in which he was trained. The majority of theologians and pastors in Germany led millions of professing Christians into either actively supporting the Nazis’ nationalist and racist ideology or at least turning a blind eye to policies and actions that violated any recognizable definition of Christian faith.

Bonhoeffer soon concluded that words were insufficient; action was necessary. Although his Protestant tradition and the influence of the great theologian Karl Barth taught him to respect the Bible as the authoritative Word of God, Bonhoeffer came to believe that determining what God wanted him to do was not a matter of principles, rules, or texts. He wrote that

The will of God is not a system of rules established from the outset. It is something new and different in each situation in life. And for this reason, a man must forever reexamine what the will of God may be. The will of God may lie deeply concealed beneath a great number of possibilities.

How does a person of faith determine the will of God? Bonhoeffer concluded that ethical behavior is rooted not in a set of principles, but in the willingness to open oneself to the will of God and do God’s command.

But how is the will of God to be discovered? I reminded my students in seminar of a text we studied a few weeks ago, Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. The centerpiece of this work is Abraham, whom Kierkegaard uses as an illustration of both the uncertainty and danger of committing oneself wholly to faith. “How did Abraham know with certainty that God had commanded him to sacrifice his son Isaac?” “He didn’t know,” several responded, remembering our conversation. Neither can Bonhoeffer be sure of what the will of God is. As recently departed Archbishop Desmond Tutu comments at a relevant point in a documentary about Bonhoeffer’s life concerning the will of God:

There is no shaft of light that comes from heaven that says “Okay, my son or my daughter, you are right.” You have to hold on to it by the skin of your teeth, and hope that there is going to be vindication on the other side.

Commit, act, then hold on by the skin of your teeth. Hardly the traditional description of following the will of God.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer evolved over the course of a couple of years from a dedicated pacifist and respected academic to the leader of an underground (and illegal) seminary and a member of the resistance movement against Hitler and the Nazis, a movement that in time fashioned several unsuccessful attempts to assassinate the Fuhrer. The vast majority of the conspirators, including Bonhoeffer, were found out and arrested. Bonhoeffer spent the last two-plus years of his life in prison. In one of his letters to his friend Eberhard Bethge, letters that have become classics in twentieth-century Christian theology and thought, Bonhoeffer wrote that

Later on, I discovered, and am still discovering to this day, that one only learns to have faith by living in the full this-worldliness of life . . .One throws oneself completely into the arms of God, and this is what I call this-worldliness: living fully in the midst of life’s tasks, questions, successes and failures, experiences, and perplexities.

Bonhoeffer’s letters from prison sketched a “religionless Christianity,” a commitment to faith that is uncertain, provisional, and dangerous. Bonhoeffer was executed, as were virtually all of his co-conspirators, just weeks before the end of World War II.

Simone Weil, whose dates are virtually the same as Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s, has the following to say about determining the will of God.

The will of God. How to know it? If we make a quietness within ourselves, if we silence all desires and opinions and if with love, without formulating any words, we bind our whole soul to think “Thy will be done,” the thing which after that we feel sure we should do (even though in certain respects we may be mistaken) is the will of God. For if we ask him for bread, he will not give us a stone.

Depending on one’s assumptions, this statement from Weil is either radically provisional or distinctly empowering. There is nothing of the certainty and confidence that persons of faith would appreciate and often seek when determining the divine will. But there is a confidence expressed that, to me at least, is entirely in keeping with the Incarnation, the central truth of Christianity that God gets into the world through human beings. As the Jewish scriptures say, “the word is very near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart, that you may obey it” (Deut. 30:14).