I, as well as the rest of the world, was saddened to hear of the death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu on the day after Christmas. Tutu, who won the Nobel Prize in 1984, was a powerful voice for change in South Africas anti-apartheid movement; he used his pulpit and spirited oratory to help bring down apartheid in South Africa and then became the leading advocate of peaceful reconciliation under Black majority rule.

I particularly appreciated Tutu’s theology, which was both hopeful and practical. My favorite quote from the Archbishop, which I have used several times over the years on this blog, is one that has often been meaningful to me when seeking guidance from a divine being who often seems silent and distant. When asked for his own insights concerning the will of God and how to know one is doing the right thing, Tutu replied that

There is no shaft of light that comes from heaven and says to you “Okay, my son or my daughter, you are right.” You have to hold on to it by the skin of your teeth and hope that there’s going to be vindication on the other side.

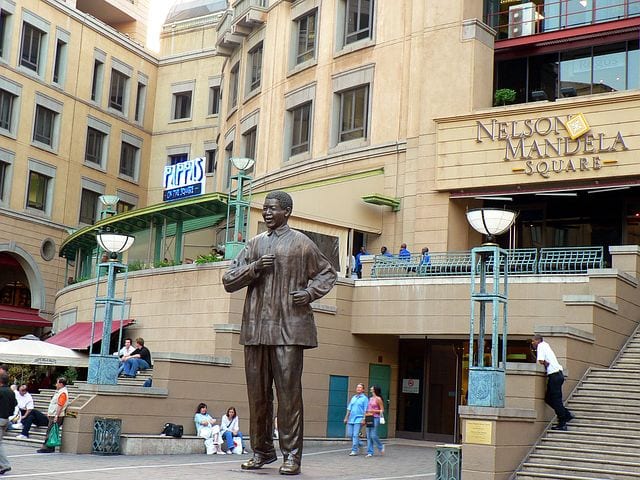

Desmond Tutu’s passing reminded me of another great South African leader, as well as of the Truth and Reconciliation commission that was established in South Africa as they sought to grapple with their fraught past and move forward after the fall of apartheid.

As we drove home from a lovely two-day celebration of our twenty-fifth anniversary several years ago, Jeanne and I were listening to NPR, as is our frequent custom when in the car. It was Nelson Mandela’s ninety-fifth birthday, and we listened to young children singing “Happy Birthday To You” outside the hospital where Mandela had been in serious condition for the past several weeks. “This guy is like George Washington,” I said to Jeanne as various people talked about Mandela’s heroic role in the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa. George Washington and Dr. King rolled into one person, perhaps. I hope he could hear the singing. Hearing about Mandela got me to thinking once again about the months I spent on sabbatical in Minnesota a decade ago, a book I read about South Africa while there, and forgiveness.

One of the many joys of morning and evening prayer at St. John’s Abbey while on sabbatical was listening to the monks read. In addition to four psalms and a canticle, the gathering reads through books of Scripture, a different book in the morning and evening. The morning non-Psalm reading after Easter was the book of Revelation—that’s so weird that I’m not even going to go there. In the evening, we read the Acts of the Apostles, full of great stories with lots of action and fascinating characters.

The Acts-reading monk one week was the same monk who read Genesis 1 at Easter Vigil a few weeks earlier. There’s a reason he was chosen to be the voice of God. He had one of those great voices, the sort of voice that could hold you spellbound reading the phone book. James Earl Jones. Morgan Freeman. The guy who narrates National Football League highlight films. This monk had a better God voice than Cecil B. DeMille’s God voice in The Ten Commandments. So it was a treat listening him to read the stories of Peter and Cornelius, the activities and antics of the early Christians in Antioch and, one memorable evening, the breakup of the original missionary duo, Paul and Barnabas.

After spending some days at Antioch recuperating from his first missionary journey, Paul decides that it’s time to take a return tour to all the various cities he and Barnabas visited, in order to see how the new converts and fledgling Christian communities are doing. Barnabas is on board with the idea, and would like to bring a new guy along, by the name of John Mark. John Mark, however, has some serious baggage. He was an unnamed companion with Paul and Barnabas on their first journey, but when things got tough in Pamphylia, John Mark packed his toga and ran back to Jerusalem. Barnabas apparently sees something promising in this timid fellow, and wants to give him a second chance.

Paul, however, is having none of it. As George W. Bush tried to say once while President, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.” And Paul isn’t going to be fooled twice—“I’ve got churches to establish, half of the New Testament to write, a religion to get off the ground, and I don’t want any quitters or losers in my entourage.” The argument becomes heated; eventually, Paul and Barnabas decide to go their separate ways. Paul takes Silas on the road as his new sidekick, while Barnabas takes John Mark with him to Cyprus, perhaps to form a new and competing missionary team. Nothing more is mentioned of Barnabas and John Mark in the book of Acts, while Team Paul and Silas go on to missionary glory and Paul invents Christianity. The winners get to write the history,

There are many differences between the God of the Hebrew scriptures and God in the New Testament—the nature of forgiveness is one of them. In the Psalms, the psalmist is forever asking God to forgive wayward and sinful Israel, or the wayward and sinful writer; God’s response is usually along the lines of “I will, if . . .” or “I will, but . . .” The God of the Jewish scriptures is occasionally a God of forgiveness and mercy, but more often is a God of justice, justice which often is indistinguishable from flat-out vengeance. Justice and forgiveness frequently seem opposed, incompatible. In the New Testament, the message of God-in-the-flesh Jesus is always about mercy and forgiveness—items which, when you think about it, are a lot more difficult to pull off than justice. Contemporary examples of Jesus-style forgiveness in action are both jarring and uncommon.

While on sabbatical in Minnesota, I read Antjie Krog’s Country of My Skull. Krog is a poet who was a reporter for South African Broadcasting Corporation radio from 1996 to 1998 during the Truth and Reconciliation hearings that took place after the fall of apartheid in South Africa. The hearings served as a forum for those accused of murder and torture to be confronted by their victims, and, by admitting their guilt, to be considered for amnesty under Ubuntu, the African custom of forgiveness. It’s a harrowing book; I was sometimes only able to read four or five pages at a time.

In a scene from the 2004 film In My Country, based on Krog’s book, a young African boy, perhaps eight years old, is sitting in the victim’s chair; a white police sergeant, who killed the boy’s parents a year earlier as the boy watched, is sitting ten feet away behind a desk. The boy has not spoken since the murders. The sergeant, who was only “obeying orders,” is now wracked with remorse and guilt. Coming from behind the desk, he says to the amnesty panel “I can’t eat, I can’t sleep! I’ll take care of him! I’ll pay his school bills!” Tears streaming down his face, he kneels in front of the orphaned boy. “Let me do something!” The boy slowly stands and looks the kneeling policeman in the eyes for what seems like an eternity. What will he do? Strike him? Spit on him? The boy leans slightly toward the policeman, then falls on his neck and embraces him. The love and forgiveness of Christ, insane, impossible, and divine.

Back to Paul and Barnabas. On one level, it’s not difficult to understand why Paul refused to forgive John Mark’s cowardice, at least to the extent that he didn’t want to risk taking John Mark on another journey. But I wonder if Paul remembered where he himself had come from. What if Ananias had not, in fear and trembling, taken this persecutor and murderer of Christians into his home and been Christ to him in the spirit of total forgiveness? Sure, the Lord told him to do it, but Jesus tells us to do the same thing. Immediately after the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew, Jesus says “if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.” But I think this is hyperbole. In fact, I am forgiven whether I forgive or not. And I’m forgiven whether I like it or not. Barnabas was right. I hope he and John Mark enjoyed Cyprus.