The final meeting of my honors colloquium on Michel de Montaigne was last Thursday. It was a beautiful day, and I wasn’t surprised when my students wondered if we could have our final seminar in an alternative setting. I expected them to suggest that we move outside; I would have grudgingly agreed even though it is the peak of allergy season.

But instead they wanted to meet at MacPhails, our on campus pub. All of the students are of legal drinking age (barely); I readily agreed to move across campus and enjoy a beer with Montaigne.

The text for the day was “Of experience,” the lengthy final essay in Montaigne monumental Essais that had been our primary text for the whole semester. The essay is full of memorable passages, but one in particular caught my attention this time around:

There is as much freedom and latitude in the interpretation of laws as in their creation. And those people must be jesting who think they can diminish and stop our disputes by recalling us to the express words of the Bible.

I know Montaigne well, but had forgotten this insight, one that I could have used fruitfully in responding to a bunch of evangelicals who were outraged by one of my recent essays and weaponized passages from the Bible to thwart my heretical tendencies. My experience with the Bible is lifelong and complicated. Here’s one of the early essays from more than a decade ago on this blog that delves into that experience. Enjoy “Sword Drills” from April 2013!

On one of my family’s summer western treks, we pulled into a Phillips 66 station to fill up. “What does the 66 stand for?” my dad asked, to which I immediately guessed “the 66 books of the Bible?” “Right,” he said. Although I found out many years later that this is not true, don’t blame my dad for feeding me false information. Many people thought that the number in Phillips 66 came from the books of the Bible, and the founder of Phillips Petroleum Company didn’t straighten people out about the name’s origin for years. Good publicity to keep people guessing.

One of the first facts I learned about the Bible is how many books it contained. And I knew them cold. In Sunday school, little Baptists learned songs whose lyrics were the books of the Bible in order as soon as they learned to talk (usually before they learned to read). I still remember the song for the tricky minor prophets, the last twelve books of the Old Testament. I used to sing it on command at an early age very quickly in one breath–hosea-joel-amos-obadiah-jonah-micah-nahum-habbakuk-zephaniah-haggai-zechariah-GASP!-malachi-for the entertainment of my parents and their guests. At Bible camp one year there was a girl who could say the books of the Bible backwards (all of us could say them in correct order). I didn’t exactly see what the practical applications of that skill might be, but it was impressive.

Once we got a bit older, around eight or so, we learned another skill in Sunday School: how to find any verse in the Bible as quickly as possible. To hone this skill, we had competitions called “sword drills,” since Paul calls the word of God the “sword of the spirit” in Ephesians. Our teacher would say “draw your swords,” and we would raise our Bibles in one hand above our heads. Each of us had brought ours from home, of course—I don’t know what would have happened to someone who forgot their Bible, since I don’t recall it ever happening.

The teacher would then call out a Bible reference—book, chapter, and verse—and then, after a tantalizing pause, would shout “GO!!” Whoever found the scripture and started reading it first won. And I was good. I mean REALLY good. I had a cousin who used to win infrequently (maybe once every ten times), but other than that it was all me all the time. If the teacher said “John 3:16!” I would roll my eyes and think “Please. That’s in the Gospels. I know that one by heart—give us something challenging.” “Psalms 101:11!” “Come on, I can win that with one hand tied behind my back.”

“Micah 6:8!” “Lamentations 4:2!” “Habakkuk 3:17!” “Now you’re talking,” I thought, as I got the verse then waited a moment, just to make things interesting, while my fellow sword-wielders fumbled around, reading the verse just as the kid next to me was getting ready to read it. “Now we’re separating the real sword masters from the wannabes.” “Hezekiah 17:32!” I watched my comrades with disdain as they leafed through their swords, pitying them and how foolish they would feel when they found out it was a trick command—there is no book of Hezekiah in the Bible. I wasn’t very good at traditional sports like football and basketball, but man I could wield a sword. Introducing sword drills to my Catholic students a few years ago was a hoot, especially since for many of them it was the first time they had ever cracked a Bible.

So imagine my reaction—dismay, shock, outrage—when I found out that some people (who shall remain nameless) added some extra books to the Bible, jammed in between the Old and New Testaments, and actually thought this is acceptable! I can remember exactly when it happened. In the late sixties and early seventies (my junior high and high school years), several new translations of the Bible came out. This was disturbing enough, since in my crowd “King James” was not a basketball star—“King James” was the name of the only authoritative translation of the Bible.

We were taught to believe that the Bible is the inerrant word of God; no one corrected us when we additionally assumed that God had dictated the book in King James English to a bunch of guys in the 17th century. But when I looked in one of these new translations and saw a bunch of unfamiliar books under the collective title “The Apocrypha,” I thought “What the hell is this??” “First and Second Maccabees”? “Baruch”? “The Song of the Three Men”? “Tobit”? That sounds like something from Tolkien: “In a hole in the ground lived a tobit.” “Bel and the Dragon”? What’s that, a comic book? I didn’t know what to think, except that someone had been messing around with my Bible, and I was pissed.

I have to admit that, although it’s now over fifty years later, I’ve never read any of these books in their entirety. There are some bits and pieces of apocryphal books in the Episcopal prayer book as canticles for morning and evening prayer, which isn’t surprising since we Episcopalians are willing to appropriate anything from any tradition so long as it is good liturgy, fine music, or profound literature, always assuming that it will also support a liberal, left-leaning mindset. But I still feel a bit odd reading parts of “The Song of the Three” or “The Prayer of Manasseh,” as if I’m doing something wrong. Old habits and beliefs die hard, especially when they were established in the cradle.

I stopped believing that the Bible is the inerrant, literal word of God while still in my teens (I’m not sure I ever really believed it), and have occasionally wondered since then exactly what the Bible is for me now. It is part of my tradition, my heritage, and my history. I am forever grateful that I had the opportunity, although often a forced one, to make its stories, its poetry, its history, part of my intellectual foundation at a very early age—foundations laid at such an age remain largely intact. I rely on that foundation every day in the classroom and during outside-of-class conversations with students and colleagues. It is a shared touchstone in Jeanne’s and my life. And I still am thoroughly comfortable with calling it the word of God—but what exactly does that mean?

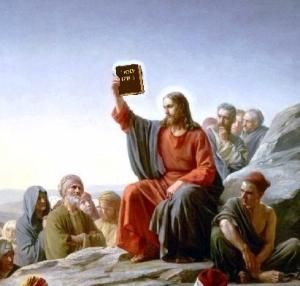

I recall a memorable Sunday evening in my early twenties when a venerable Bible scholar, an elder at the large church my family was attending and the godfather of my then six-month-old firstborn son, stood behind the pulpit, raised his Bible above eye level for all to see (almost like a sword drill) and said with great courage to a largely evangelical congregation: “This is not the word of God! This is a bunch of pages between leather covers written by human beings. It becomes the word of God when the Holy Spirit writes its message in your heart. Remember, the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life.” Other than a gasp or two, you could have heard a pin drop.

But he was right. As I’ve returned to the texts of my youth over the past years in both communal and private reading, new life has risen in me. Noon prayer in the Benedictine liturgy of the hours always begins with several verses from Psalm 119, which is the longest chapter in the Bible and is all about the glories of God’s word. The Psalmist never says a thing about the written word—God’s word always is hidden in our hearts, written in our minds, lived out in our actions. And as my son’s godfather implied, the Spirit can transform anything, any text, written or otherwise, into the word of God. The Bible in my experience is special because it is at the heart of what I believe and its words have become God’s word for me more often than any other source. But it could be Shakespeare. Or Nietzsche. Or Jeanne. Or my dachshunds. Or the sun rising this morning—in a sacramental world, anything can be the word of God. Even Tobit, I suppose.