Fifteen years ago, I was part of a group of a dozen or so academics who visited Cuba for a week on a fact-finding trip related to their health care system. I returned from this experience with very different attitudes about our neighbor 90 miles to the south than I had before the trip, as I described in my article entitled “Shattering the Myths About Cuba,” included in one of my college’s publications in the Spring of 2004 . . .

The story is told that Augustine used to get annoyed at his students when, as he pointed toward something that he wished them to consider, they focused their attention on his finger instead. Anyone who is–or ever has been–a teacher will understand Augustine’s frustration. As a philosophy professor, I know that the most crucial, yet most difficult lesson to teach is the lesson of learning to “see beyond seeing,” of discovering what Bertrand Russell called “the strangeness and wonder lying just below the surface even in the commonest things of daily life.” In its most practical applications, this lesson shows us that often what we believe we “know,” what seems most self-evident and obvious, is an opaque barrier that prevents us from being open to the possibility of better knowledge.

I traveled to Cuba last summer for a week-long visit as a member of a 12-person delegation of professionals, nine of them from Rhode Island. There were a number of interrelated goals for our visit, including visiting the Latin American Medical School in Havana (where a number of American students are studying at the invitation of President Fidel Castro, free of charge), learning firsthand about Cuba’s admirable universal health care system, visiting a number of multicultural centers to learn about Cuba’s commitment to education and cultural development, and laying preliminary foundations for educational exchanges between Cuban and Rhode Island institutes of higher education.

The greatest impact of this trip on me, however, was that it shattered everything I “knew” about Cuba. This shattering has made it possible for me to reflect ever since my return on what the undermining of these “truths” might reveal concerning deeper human issues.

I was born in the 1950s, in the middle of the Cold War. One of my earliest memories from the nightly television news was the failed Bay of Pigs invasion; I was 6 years old during the perilous days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. My attitudes concerning Cuba were fashioned during those early years and remained largely the same ever since. I did not claim to know much about Cuba, but there were several things that were clear and beyond question. Cuba is an enemy, aligned with everything our country despises–a likely terrorist state, a repressor of religious and secular freedoms, a violator of human rights, an embarrassing challenge to what is most near and dear to us, a mere 90 miles off our coast.

Not that I, as an educated, independent thinking adult would ever have consciously allowed that I carried these largely unchallenged assumptions around with me; I’m not sure that I knew of my preconceptions until I visited Cuba. I never even thought about Cuba except when some event deemed newsworthy, such as the Elian Gonzalez case, brought the island to my attention. When, before the delegation’s trip to Cuba, I was asked what my expectations of the visit were, I continually said that I had no expectations–I was going with an open mind, the classic case of the tabula rasa, the “blank slate” that John Locke claimed all human beings are born with. Little did I know just how much would have to be erased from my slate before I could truly see.

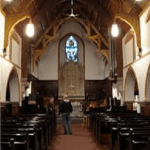

I, for instance, thought that I “knew” there was very little, if any, religious freedom in Cuba. After all, Cuba is a Communist country whose official stance on religion, in the style of the former Soviet Union, is atheism, right? Imagine our surprise when we discovered that religious faith is not only alive in Cuba, it is flourishing.

On a bright and sunny Father’s Day morning, our delegation’s first full day in Cuba, we attended services at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Marianao, one of the many economically impoverished neighborhoods in Havana. In a hot and stuffy auditorium packed with persons of all ages and colors, we observed the most active and vibrant church service that I, a lifelong churchgoer, have experienced in years. The worship was filled with contemporary liturgical dance, congregational singing and participation, and testimonials (including a touching tribute to fathers from a young girl around 12 years of age, read in Spanish and English, that brought tears to the eyes of many of the fathers present). After this, the pastor and one of his guest ministers from Colombia delivered brief talks about the need for men to overcome “machismo” and open their minds and hearts to the voices of women.

Uncovering false “truths”

Two days later, more “truths” about Cuba were proven false when our delegation had the opportunity to return to Ebenezer Baptist and its accompanying Martin Luther King, Jr. Center in order to meet with Rev. Raul Suarez, the pastor of the church. When the Cuban Revolution succeeded in 1959, 90% of the pastors in Cuba fled for other countries, believing that religion and belief in God would no longer be tolerated. Rev. Suarez and a few others stayed, however, He explained, in his own words, “If Communism is the big bad wolf, we need to protect our sheep.” By staying, he realized immediately that the lives of the people in Cuba were being improved by the Castro government’s commitment to 100% literacy, to universal health care and education, to true socialist principles, and to equal access to and excellence in sports and the arts.

Rev. Suarez described for us how the Cuban Revolution caused him to rethink his faith and evolve from a conventional Southern Baptist minister to a proponent of “liberation theology,” from advocacy of spiritual wealth in the next world to a vision of radical social change in this world, and from silence to active leadership in the struggles against racism, poverty, and other societal ills. He described that he had been taught what Christians supposedly could not have (they could not smoke, dance, drink, etc.), but “no one taught us that poverty is a sin. That ignorance is a sin. That racism is a sin. That economic inequality is a sin. The Revolution taught us that.”

His church, once a largely white church in a predominantly black neighborhood, is now a powerful instrument for social change and improvement, dedicated to the betterment of human lives as they are lived in this world as well as to the tending of spiritual needs.

Church and State dialogue

So how do things stand between church and state in Cuba? Very differently than U.S. citizens are led to believe. Over the past 20 years, there has been a continuing dialogue between Cuban ministers of all faiths and the Cuban government. At the first of these meetings, the ministers told Fidel Castro that the official position of atheism was hurting the Cuban people and that Christianity is a religion meant to help the people, not to be enclosed within church walls. Castro said to the ministers: “You work in your churches and help them to understand us better, and I’ll work with my people and help them to understand you better. And my work will be more difficult than yours.”

Incrementally, things changed so that by 1991, atheism was eliminated as a requirement for membership in the Communist party, all reference to Marxism/Leninism as the official philosophy of the Cuban government was eliminated from the constitution, Christians were allowed access to all professions, were granted full access to all means of communication to spread the good news of the Gospel, and were allowed to establish new congregations across the country. The congregations of all denominations in Cuba are continuing to grow rapidly to this day.

This is but one example of how the truth about Cuba turned out to be quite different than what I believed it to be. I could have written a similar article about the political process in Cuba, human rights violations in Cuba compared to such violations in this country, or how our “free” press in the United States regularly distorts the truth about what is occurring in Cuba.

As a philosopher, I find an important lesson beneath these different factual issues. As human beings, our frequent natural tendency is to assume that we know the truth about a given thing, then to selectively interpret the “facts” to fit our preconceived piece of knowledge. Whether in religion, politics, social structures, interpersonal relationships, or simply regular day-to-day existence, this is a tendency that must be actively and consciously resisted.

The truth, for human beings at least, does not come in bumper sticker-sized, “sound bite” form. To believe that it does leads to rigidity, absoluteness, and blindness to the evolving nature of our interaction with what is true. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the 20th-century German Protestant theologian murdered by the Nazis in the final days of World War II, wrote, “The responsible man has no principle at his disposal which possesses absolute validity and which ha has to put into effect fanatically, overcoming all the resistance which is offered to it.”

In a world of ideology presented as self-evident certainty, the following warning from Albert Camus is worth taking seriously: “On the whole, men are more good than bad; that, however, isn’t the real point. But they are more or less ignorant, and it is this that we call vice or virtue; the most incorrigible vice being that of an ignorance that fancies it knows everything . . .”