Discovering a new author is one of my favorite things–it frequently happens during the holiday season between semesters. My latest discovery is Rachel Held Evans. I received two of her books as part of my small library of Christmas presents; I’ve already finished Faith Unraveled and have started Searching for Sunday. Her work resonates with me because her story is somewhat similar to mine, an emergence from Protestant fundamentalism toward what one of my students once described as “a more nuanced and interesting faith.”

One of the theological sticking points for Evans that she carried from her youth is the exclusivity of a God who apparently had no problem with sending the vast majority of persons to hell for failing to follow the narrow path to salvation endorsed by the church in which she was raised. Evans refers to the “cosmic lottery,” in which by accident of birth, race, gender, and location some appears to be divinely favored and others divinely condemned from birth. The randomness of worshiping a God who favored some persons at the expense of others for obscure and frivolous reasons wore on her to the point of stepping away from faith altogether.

Then during a night of insomnia, Evans read a passage from the Gospel of Luke where Jesus indicates that those whom God chooses are not only restricted to our own selective criteria, but also are likely to include precisely those people who we would be quickest to exclude. In answer to the disciples’ question “Lord, are only a few people going to be saved?” Jesus says

People will come from east and west and north and south, and will take their places at the feast in the kingdom of God. Indeed there are those who are last who will be first, and first who will be last.

Sitting in her bathroom in the middle of the night, Rachel Held Evans began to imagine just what this expansive and motley crew of people might look like; her description reminded me of a similar vision provided by one of Christianity’s sharpest and most unusual apologists.

In Flannery O’Connor’s short story “Revelation,” Ruby Turpin, one of O’Connor’s most memorable characters, has a very bad day. Ruby and her husband Claud own a small farm in 1940s Georgia—their livelihood is made from the yield of their acres worked by hired black workers and the raising and sale of a few cows, pigs and chickens. The bulk of the story is set in the waiting room of a crowded doctor’s office where Ruby and Claud wait for the doctor to look at an infected area on Claud’s leg where he was kicked by a cow a few days ago.

Ruby is a chatty, pleasant, overweight, confident Christian woman in her forties with, as she frequently says, a “good disposition,” and tends to immediately strike up a conversation with whoever is willing. Other patients in the room include a well-dressed woman with a sullen, ugly teen-aged daughter, a grandmother, mother and son who are obviously “white trash,” and others who flit around the edge of the conversation.

It becomes immediately clear that Ruby has a strong sense of how things are supposed to work and of the proper hierarchy of persons in her world. She is thankful that God didn’t make her a “nigger, or white-trash, or an imbecile”—she is extraordinarily grateful that she was born with a good disposition, is blessed with enough food and money (although not too much), and is generally just thrilled to be herself. As she drops these tidbits into her conversation, as well as comments about why Negroes should perhaps go back to Africa, Ruby notices that the sullen young lady keeps shooting increasingly hostile glances in her direction.

The girl’s well-dressed mother eventually reveals that her daughter, a student at an exclusive college “up north,” has been given everything by her parents but is an “ungrateful person” with a bad attitude who never does anything but criticize and complain. Mrs. Turpin remarks that “it never hurts to smile,” concluding that “When I think who all I could have been besides myself and what all I’ve got, a little of everything and a good disposition besides, I just feel like shouting ‘Thank you Jesus, for making everything the way that it is!’” In response, the sullen college student throws the college textbook she has been reading across the room at Ruby, hitting her above the left eye, then leaps on top of Ruby and starts choking her.

Once Ruby is rescued by others and the young lady, “obviously insane,” is sedated, Ruby asks “Don’t you have something to say to me?” The girl responds in a vicious whisper “go back to hell where you came from, you old warthog!” As the day winds on, Ruby, despite her good disposition, can’t shake this comment from her consciousness. Back on the farm toward sunset, as she hoses mud off the pigs, Ruby’s mounting anger ignites in a direct and explosive tirade aimed at the very God she had been thanking earlier.

What do you send me a message like that for? . . . It’s not trash around here, black or white, that I haven’t given to. And break my back to the bone every day working. And do for the church. How am I a hog? Exactly how am I like them? There was plenty of trash there. It didn’t have to be me. If you like trash so much, go get yourself some trash then. You could have made me trash. Or a nigger. Go on! Call me a hog! Call me a hog again! CALL ME A WART HOG FROM HELL! . . . WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE??

When Ruby comes up for air, she raises her eyes to where the sun has just slipped below the horizon. And she suddenly sees–really sees–for the first time that day, perhaps for the first time in her life.

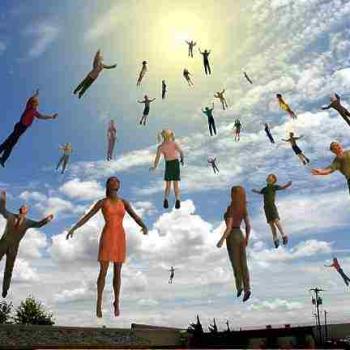

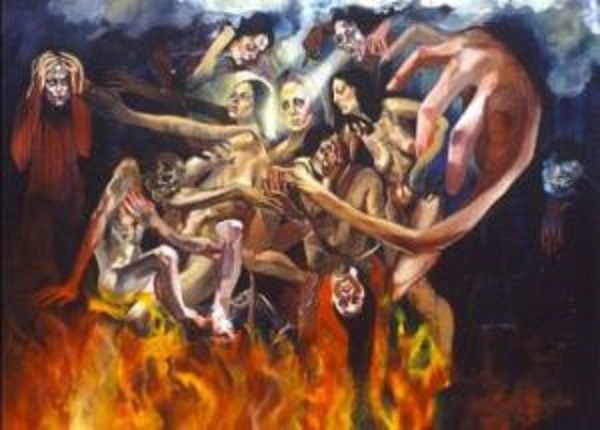

A visionary light settled in her eyes. She saw . . . a vast swinging bridge extending upward from the earth through a field of living fire. Upon it a vast horde of souls were rumbling toward heaven. There were whole companies of white-trash, clean for the first time in their lives, and bands of black niggers in white robes, and battalions of freaks and lunatics shouting and clapping and leaping like frogs. And bringing up the end of the procession was a tribe of people whom she recognized at once as those who, like herself and Claud, had always had a little of everything and the God-given wit to use it right . . . She could see by their shocked and altered faces that even their virtues were being burned away. . . . In the woods around her the invisible cricket choruses had struck up, but what she heard were the voices of the souls climbing upward into the starry field and shouting hallelujah.

And the story ends. Something has broken through Ruby’s safe and smug assumption that God’s behavior and expectations fit her comfortable world seamlessly. Did the vision change her life? Did she forget it in the next minute? O’Connor wisely leaves it to us to wonder.

God’s program is not ours—God’s priorities are upside down. But that’s the point. A transformed world requires transformed people. Only an entire rearranging of what is “natural” will suffice. Be on the lookout for moments of holiness, the small but persistent ways in which the faith we profess turns everything upside down.