The opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty Anne Lamott

In the lectionary, the Second Sunday of Easter is “Doubting Thomas Sunday.” I was taught as a young Baptist kid to consider Thomas as a loser because he would not believe reports of Jesus’ resurrection until he had seen and handled the man himself. But over the years, Thomas has become one of my spiritual heroes, and doubt (along with irreverence) has become my favorite virtue. Here’s why.

Michel de Montaigne’s world was filled with religious fervor and piety. It was also filled with hatred and violence. Sixteenth-century France was not a pretty place—in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation, Christians were killing each other with regularity and abandon, all in the name of Christ. Catholics and Protestants each were certain that they were right; energized by such certainty, each was willing to kill the other in the name of truth and right belief.

Michel was an upper class landowner and occasional politician—he was mayor of Bordeaux for two terms as well as a trusted diplomat and liaison. Sensitive and melancholy by nature, Montaigne was appalled by the violence that was tearing his country, his town, his neighborhood, even his own family apart. Accordingly, in his middle years he did what any introverted, sensitive, melancholy guy would have done. He withdrew to his turret library in the small castle on his family estate and wrote—for the rest of his life.

His finely honed powers of perception fueled his creative energies, with thousands of words spilling out onto the page often more quickly than he could think. The result, Montaigne’s Essais, consists of fascinating and brilliant bite-sized essays on every topic imaginable, from cannibals and sexual preferences to Michel’s favorite food, his kidney stones, and his cat. And in the midst of this loosely organized jumble of creativity and insight, Michel frequently sounds like Rodney King in the midst of the Los Angeles riots—“Can’t we all get along?” I’m looking forward with great anticipation to teaching an Honors colloquium next spring for the first time exclusively focused on Montaigne’s Essais.

Montaigne writes that “there is no hostility so extreme as that of the Christian. Our zeal works marvels when it seconds our inclination toward hatred, cruelty, ambition, greed, slander, and rebellion.” This was the world in which he lived. Michel’s antidote? Let’s stop claiming to be certain about what we believe and try some healthy doubt and skepticism on for size. Certainty is vastly overrated and is frequently dangerous, especially when claimed in matters that are far beyond the reach of human capacities. Montaigne is convinced that for the most part, human beings are not designed for the rarified air of certainty. He directly challenges those who “claim to know the frontiers and bounds of the will of God,” observing that “there is nothing in the whole world madder than bringing matters down to the measure of our own capacities.”

Is there anything more ludicrous, he asks, than our propensity to believe most firmly that which we know least about and to be most sure of ourselves when we are farthest from what we can verify? Human beings claiming certainty about the will and nature of God would be humorous, and Michel often presents it that way, were it not that such claims are often the basis for the worse of what human beings are capable of, including prejudice, violence, and killing. Even as we seek preposterously to elevate ourselves to the level of the divine, Montaigne reminds us that we remain rooted in our humanity. “There is no use our mounting on stilts, for on stilts we must still walk on our own legs. And on the loftiest throne in the world we are still sitting only on our own ass.”

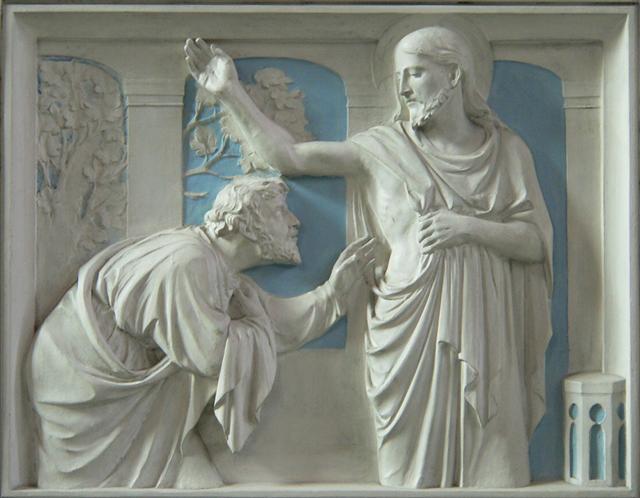

Because of his willingness to embrace messiness and uncertainty as part of the human experience, because of his willingness to call chaos what it is and not something else, Montaigne is one of my heroes. So, as a matter of fact, is the star of today’s gospel—Thomas. “Doubting Thomas,” as he almost always is described, occupies a unique place in the line-up of disciples. He’s the one who wouldn’t believe that Jesus had risen, wouldn’t believe second-hand reports from eye witnesses, until he saw Jesus himself, until he saw the wounds in his hands, feet and side. Thomas was always brought to our attention in Sunday School as someone not to be like; indeed, Jesus’ put down of Thomas after Thomas finally believes—“Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe”—provides us two thousand years later with something to be proud of. We, not having seen, are the blessed ones while Thomas (the loser) gets in by the skin of his teeth.

But there is another way to read this, a way in which Thomas turns out not to be a spiritual weakling, but rather to be a model of how to approach the spiritual life. We don’t know much about Thomas apart from this story; he is included in the list of disciples in the first three gospels, but John is the only gospel in which Thomas makes an appearance. He’s not one of the inner circle, but occasionally makes appropriate comments and asks good questions. In John 20, John’s account of the resurrection and its aftermath, we find the disciples, minus Thomas, hiding in a room with the doors locked “for fear of the Jews.” Peter and John have already seen the empty tomb, but there is an atmosphere of confusion, uncertainty and fear in the room. Jesus appears to them, and all uncertainty vanishes. But Thomas was not there.

Where was he? Perhaps he wasn’t as afraid as the other disciples and was out and about on that first day of the week, as were the women who first saw the empty tomb. Perhaps he was on a food run for the rest of the disciples who were too frightened to emerge from their safe house. But he misses the big event. When the other disciples report that “we have seen the Lord,” Thomas’ response places him forever in the disciples’ hall of shame: “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.”

Fair enough, I say. Remember that the other disciples apparently did not believe until Jesus appeared to them. The disciples on the road to Emmaus did not recognize that Jesus was with them until he emerged from the pages of the Old Testament prophecies that he was pontificating about and broke bread with them. Why should Thomas not be cut the same slack? Embedded in the middle of this misunderstood story is a fundamental truth: A true encounter with the divine is never second-hand. Hearing about someone else’s experiences, trying to find God through the haze of various religious and doctrinal filters, is not a replacement for the real thing.

Doubt and uncertainty are central threads in the human fabric and play a fundamental role in belief. Unfounded claims of certainty undermine this. Don’t believe on the cheap. Better to remain uncertain and in doubt one’s whole life, doggedly tracking what glimmers of light one sees, than to settle for a cheap knock-off or a counterfeit. As Annie Dillard writes, “Doubt and dedication often go hand in hand.” Thomas’s—and Michel’s—insight is captured well by the remainder of the passage from Anne Lamott with which I began this post:

The opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty. Certainty is missing the point entirely. Faith includes noticing the mess, the emptiness and discomfort, and letting it be there until some light returns.

Thomas was right. We should save “My Lord and my God” for the real thing.