Bein’ born is craps. How we live is poker. Doc Holliday

Of the dozens of novelists whose books I have read over the years, Mary Doria Russell is one of my least likely favorites. I’m not a big science fiction fan (I much prefer mysteries), but her debut novels The Sparrow and Children of God, about a Jesuit missionary expedition in outer space (you can’t beat Catholics in space!) are both beautifully written and thought-provoking. Dreamers of the Day, set in Egypt during the post-World War One partitioning of Palestine, is much better than I expected it would be. I avoided her next two novels, Doc and its sequel Epitaph, which follow Doc Holliday and the Earp brothers through late nineteenth-century Dodge City and Tombstone, for quite a while since I’ve never been a fan of Wild West fiction. But a couple of summers ago I was looking for some new fiction to read, so Doc and Epitaph it was. I highly recommend them.

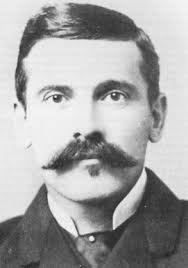

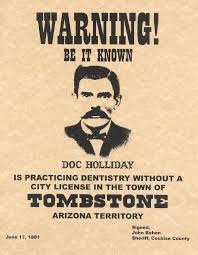

Doc is set in 1878 Dodge City where the genteel and consumptive dentist John Henry “Doc” Holliday finds himself scratching out a living as a card shark by night and a sometimes-dentist for cowboys who have never seen a toothbrush by day. A Northern-educated Southern gentleman who headed west hoping that the dry Plains air might be good for his lungs, Doc finds himself in a violent world where life means little and in which most of his acquaintances can barely read, let alone appreciate his conversational references to Virgil and Dostoevsky. One exception is Morgan Earp, the youngest of three Earp brothers in town, who is a policeman along with his older brother Wyatt. Wyatt can barely read, but Doc happily loans Morgan favorite volumes from the library he brought with him from Georgia, including Crime and Punishment and Oliver Twist.

One morning Morgan is in Doc’s dentist office as Doc extracts several teeth from a chloroformed Wyatt, Doc and Morgan discuss the novels Morgan is reading.

- Doc: Morgan, how are you and Mr. Dickens getting along?

- Morgan: I like him better than Dostoevsky. Oliver Twist reminds me of Wyatt when he was a kid.

- Doc: You met Mr. Fagin yet?

- Morgan: Yeah. Ain’t made up my mind about him. He’s good to feed all those boys, but he’s teaching them to be pickpockets too. That don’t seem right.

- Doc: But that is just what makes Fagin interestin’. Raskolnikoff, too. Fagin does his good deed with a bad purpose in mind, but the boys are still fed. Raskolnikoff kills the old woman, but he wants to use her money to improve society. As Monsieur Balzac asked, May we not do a small evil for the sake of accomplishin’ a great good?

- Morgan: I don’t know. It’s still an evil.

- Doc: And yet, that seems to be the principle behind the crucifixion. Sacrifice the Son, redeem humanity.

And there, in a dentist office in dusty, dirty Dodge City, is the heart of one of the greatest quandaries in ethics. Do the ends ever justify the means? Is it ever morally permissible to act immorally in the attempted achievement of a great moral good?

And there, in a dentist office in dusty, dirty Dodge City, is the heart of one of the greatest quandaries in ethics. Do the ends ever justify the means? Is it ever morally permissible to act immorally in the attempted achievement of a great moral good?

Philosophers love this stuff. The other day when I tried to get a colleague and friend from the English department to choose whether she would choose to support our Providence Friars basketball team or the University of Virginia Cavaliers (UVA is her beloved alma mater) if they played in the Final Four, she asked “Is this one of those philosophy games where you give someone completely unrealistic hypotheticals and then force them to make a choice?” She undoubtedly had heard philosophy puzzles such as

Suppose an out-of-control train is running down the tracks directly at a bus full of 30 people stalled on the track. You have the opportunity to redirect the train to another track where one person is stalled in a car on the track.  If you don’t pull the switch to redirect the train, thirty people will die. If you do, one person will die and thirty people’s lives will be saved. Do you pull the switch?

If you don’t pull the switch to redirect the train, thirty people will die. If you do, one person will die and thirty people’s lives will be saved. Do you pull the switch?

To complicate matters, suppose that the one person on the second track is a brilliant scientist who is on the edge of discovering a cure for cancer. Does that make a difference? What if he or she is a homeless person? You get the point.

Surprisingly, non-philosophers don’t always enjoy playing such hypothetical games (by the way, my colleague said she would cheer for UVA, which almost ended our friendship instantly). But the issues raised by Morgan and Doc’s conversation still hold.  Was it morally permissible for Raskolnikov to murder the useless old miserly woman in the interest of distributing the millions of rubles she was hoarding to hungry and needy people? Does Fagin’s feeding of dozens of hungry children lose its positive moral strength when we find out that he is training them to be pickpockets and becoming rich in the process?

Was it morally permissible for Raskolnikov to murder the useless old miserly woman in the interest of distributing the millions of rubles she was hoarding to hungry and needy people? Does Fagin’s feeding of dozens of hungry children lose its positive moral strength when we find out that he is training them to be pickpockets and becoming rich in the process?

Many philosophers and theologians have noted that in an unpredictable world filled with evil, no one’s hands are ever morally pure—regardless of their intentions. Doc and Morgan’s conversation moves in this direction.

- Doc: We’re none of us born into Eden. World’s plenty evil when we get here. Question is, what’s the best way to play a bad hand?

- Morgan: The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

- Doc: Infinitely sad, but damnably true. Bein’ born is craps, but how we live is poker. The question is how to play a bad hand well.

The great Stoic philosopher Epictetus could not have said it better: “For this is your business, to play well the part you are given; but choosing it belongs to another.”

Looking ahead on the liturgical calendar, I would be remiss if I did not return for a moment to Doc’s characterization of the events of Good Friday and Easter: “That seems to be the principle behind the crucifixion. Sacrifice the Son, redeem humanity.”  Maybe, but something tells me that a utilitarian number-crunching calculus is not the motivating factor behind Easter. At the heart of the story is radical love—God responds to our flawed human condition by becoming one of us, taking on everything that defines us including pain, injustice, suffering, and death. The new life of Easter emerges from the worst that our world can offer, just as the hyacinths are poking their heads out of the seemingly dead grass in my front yard. No matter the hand we’re dealt, that’s the way to play it.

Maybe, but something tells me that a utilitarian number-crunching calculus is not the motivating factor behind Easter. At the heart of the story is radical love—God responds to our flawed human condition by becoming one of us, taking on everything that defines us including pain, injustice, suffering, and death. The new life of Easter emerges from the worst that our world can offer, just as the hyacinths are poking their heads out of the seemingly dead grass in my front yard. No matter the hand we’re dealt, that’s the way to play it.