As those who love Masterpiece Theater and great television know, “Downton Abbey” is in the middle of its sixth and final season on Sunday nights here in the U. S. I’ve written frequently about what I’ve learned from this show–here’s a post about my favorite Downton character from a bit over a year ago . . .

In anticipation of Season Five of “Downton Abbey” making it across the pond to PBS next month, Jeanne and I just finished binge-watching Season Four over the last few evenings to remind us, first, of exactly what is going on in the lives of the two dozen or so characters in the middle of the 1920s and, second, just why this is probably our favorite show on television. That’s saying a lot. We love good television and have several series that we keep up with religiously, including “The Newsroom” which just finished its final season (bummer) and “Homeland” which is close to the end of its fourth season. We are anxiously awaiting the return of “The Americans” next month on FX for a new season. But “Downton Abbey” is a phenomenon in our house, just as it has been for millions of other viewers. No violence, no nudity or sex, no f-bombs—just great character development and brilliant acting from top to bottom. Who knew that people would like something like that?

In anticipation of Season Five of “Downton Abbey” making it across the pond to PBS next month, Jeanne and I just finished binge-watching Season Four over the last few evenings to remind us, first, of exactly what is going on in the lives of the two dozen or so characters in the middle of the 1920s and, second, just why this is probably our favorite show on television. That’s saying a lot. We love good television and have several series that we keep up with religiously, including “The Newsroom” which just finished its final season (bummer) and “Homeland” which is close to the end of its fourth season. We are anxiously awaiting the return of “The Americans” next month on FX for a new season. But “Downton Abbey” is a phenomenon in our house, just as it has been for millions of other viewers. No violence, no nudity or sex, no f-bombs—just great character development and brilliant acting from top to bottom. Who knew that people would like something like that?

I learned many months ago that if I was a character on “Downton Abbey,” I would be the stodgy and formal Mr. Carson.

Which Downton Abbey character are you?

And that’s fine with me. Mr. Carson runs the staff similarly to how I run the academic program I direct, with a firm hand and an occasional adjusting of the rules when appropriate. I’m a bit concerned about Mr. Carson’s attachment to tradition and fear of new things, but he’s loosening up a bit as the seasons progress. The main reason I resonate with Mr. Carson is his penchant for pithy and insightful one-liner comments on what is going on around him, a talent rivaled in Downton only by the Dowager Countess of Grantham Violet Crowley upstairs. Here are a few Carsonian observations from the early episodes of Season Four:

I always thought there is something foreign about high spirits at breakfast.

Here’s a difference between Mr. Carson and me—he’s not a morning person and I am. I’m at the gym every morning at 6:00. I would much rather teach at 8:30 than at 1:30 (which is my nap time). But the kind of morning person I am is not the sort which is inclined to “high spirits.” I love the morning because it is quiet, because if there is any time during the day that I will be able to slip immediately into “centered” mode, it is when I first get up. As I read the appointed Psalm 90 this morning, I read

Here’s a difference between Mr. Carson and me—he’s not a morning person and I am. I’m at the gym every morning at 6:00. I would much rather teach at 8:30 than at 1:30 (which is my nap time). But the kind of morning person I am is not the sort which is inclined to “high spirits.” I love the morning because it is quiet, because if there is any time during the day that I will be able to slip immediately into “centered” mode, it is when I first get up. As I read the appointed Psalm 90 this morning, I read

In the morning, fill us with your love;

We shall exult and rejoice all our days

and a reading from Lamentations at my friend and colleague’s memorial service a couple of weeks ago reminded me that the mercies of the Lord are renewed every morning. Morning is a good time to reset and, if necessary, commit to a “redo” of previous days that didn’t work out as planned, intended or wished. As Jeanne mentioned the other day, if the Lord renews mercy every morning, then there’s no reason we cannot be merciful to ourselves. High spirits are not required.

and a reading from Lamentations at my friend and colleague’s memorial service a couple of weeks ago reminded me that the mercies of the Lord are renewed every morning. Morning is a good time to reset and, if necessary, commit to a “redo” of previous days that didn’t work out as planned, intended or wished. As Jeanne mentioned the other day, if the Lord renews mercy every morning, then there’s no reason we cannot be merciful to ourselves. High spirits are not required.

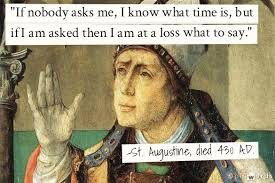

The business of life is the acquisition of memories.

One of my last classes with my Honors freshmen this semester was focused on Book Eleven of Augustine’s Confessions,  a fascinating and complex analysis of time that no philosopher matched or surpassed for a millennium after Augustine. One of his interesting questions has to do with what it is that we are focusing our attention on when we consider past events in the present. The past event is gone, but everything that we experience leaves some sort of internal impression on us, bits and pieces that we file away, consciously or unconsciously, in our “memory banks.” Each person’s history, indeed each person, is a creative stitching together of these impressions. Because we know that these internal impressions are impermanent and fleeting, we take pictures, write memoirs, and tell stories, all in the attempt to make permanent what is fleeting. Earlier in Psalm 90 this morning, the psalmist describes what we are fighting against.

a fascinating and complex analysis of time that no philosopher matched or surpassed for a millennium after Augustine. One of his interesting questions has to do with what it is that we are focusing our attention on when we consider past events in the present. The past event is gone, but everything that we experience leaves some sort of internal impression on us, bits and pieces that we file away, consciously or unconsciously, in our “memory banks.” Each person’s history, indeed each person, is a creative stitching together of these impressions. Because we know that these internal impressions are impermanent and fleeting, we take pictures, write memoirs, and tell stories, all in the attempt to make permanent what is fleeting. Earlier in Psalm 90 this morning, the psalmist describes what we are fighting against.

You sweep us away like a dream,

like grass which springs up in the morning.

In the morning it springs up and flowers;

by evening it withers and fades.

Which brings me to one more piece of wisdom from Mr. Carson.

We shout and scream and wail and cry but in the end we must all die

As Mrs. Hughes, the chief housekeeper who is the closest thing Mr. Carson has to a best friend replies, “Well, that’s cheered me up. Thank you.” Who knew that Mr. Carson is a philosopher? Mr. Carson is the epitome of English reserve, carrying the most British stiff upper lip imaginable; if he was a philosopher, he would be an early twentieth-century incarnation of the Stoicism of Epictetus or Marcus Aurelius. Stoic reserve is just one of many possible responses to a brutal and inescapable fact—we all are going to die.

As Mrs. Hughes, the chief housekeeper who is the closest thing Mr. Carson has to a best friend replies, “Well, that’s cheered me up. Thank you.” Who knew that Mr. Carson is a philosopher? Mr. Carson is the epitome of English reserve, carrying the most British stiff upper lip imaginable; if he was a philosopher, he would be an early twentieth-century incarnation of the Stoicism of Epictetus or Marcus Aurelius. Stoic reserve is just one of many possible responses to a brutal and inescapable fact—we all are going to die.

Impermanence and loss is a continuing theme throughout the seasons of “Downton Abbey,” through the ravages of World War I in Season Two to the tragic death of the heir to the family fortune in a car crash at the end of Season Three, a loss that is the connecting thread throughout all of the Season Four episodes that Jeanne and I finished watching last evening. By the end of the season some people are moving on, good fortune has smiled on others, but an uncertain future faces them all. This isn’t BBC drama—this is real life. One of the interesting attractions of “Downton Abbey” is that happiness and despair, misfortune and luck, triumph and defeat, are features of everyone’s lives—upstairs and downstairs, privileged and struggling, the family and the help.  An extended study of life as it happens does not require spies, blowing things up, gratuitous torture and dismemberment, or naked boobs and butts every week. All it requires is noticing how life actually happens to us. As Violet, the imperious Dowager Countess of Grantham tells her struggling and star-crossed granddaughter Edith, “Life is a series of problems that we need to solve—first one, then another—until we die.” Ain’t it the truth.

An extended study of life as it happens does not require spies, blowing things up, gratuitous torture and dismemberment, or naked boobs and butts every week. All it requires is noticing how life actually happens to us. As Violet, the imperious Dowager Countess of Grantham tells her struggling and star-crossed granddaughter Edith, “Life is a series of problems that we need to solve—first one, then another—until we die.” Ain’t it the truth.