Awe, not comfort….

And awe suddenly

passing beyond itself. Becomes

a form of comfort.

—Denise Levertov

Two weeks ago I flew to my childhood home in Tennessee, and twenty-nine hours after I arrived my grandmother died. Then a week after that I returned to my adult home in Philadelphia and a hurricane hit. My grandmother’s name was Gennie Vee. The hurricane’s name was Sandy. They are both gone now.

I’m not accustomed to being with someone while they die, and I’m not accustomed to being in hurricanes either. That means I had a lot to learn in the past two weeks, and not much time to learn it in. Some people call that being thrown in the deep end. Some people say that when one is thrown in the deep end, there are two options: sink or swim.

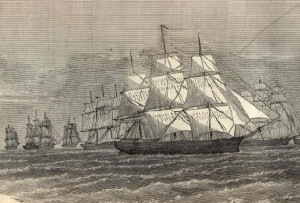

At the hospice center, a doctor with an unusually short skirt and knee-high boots took my aunt, cousin, and me into an empty room and told us it wouldn’t be long, then gave us a stapled handout titled “Preparing for the Dying Process,” and a booklet titled Gone from My Sight: The Dying Experience. The booklet was light blue, with an ink drawing of a ship with many sails making its way toward a single-lined horizon.

The literature gave straightforward information about what to expect as the body readies itself to stop working, and the mind and spirit prepare themselves to leave what they know. But, the first page of the booklet read, “Each person approaches death in their own way. What is listed here is simply a guideline, a road map. Like any map, there are many roads arriving at the same destination, many ways to enter the same city.”

For straightforward information on how to prepare for a hurricane, I Googled “how to prepare for a hurricane.” Sandy was expected to make landfall in nearby New Jersey, and because the Schuylkill River is at the bottom of our hill, I was worried about flooding and power outages. I bought candles, a lantern, batteries, canned food, bottled water, a radio, and even a blanket for good measure. I made two loaves of banana bread.

I stayed online, tracking the path of the storm—or, at least, the guideline I was given—the possible roadmap for its entrance into my city.

The advice was good, and made me feel as though I was doing something useful by following it:

Fill your bathtub with water. Unplug major appliances that are in danger of electrical surge. Fill a cooler with ice. If the power goes out, keep your refrigerator closed. If you must take something out of it, visualize what you want and where it is before you open the door.

And, from the hospice booklet, this:

Hold your loved one’s hand. Or, if you can, lie beside them and hold them. Play calming music. Speak to them softly even if they do not speak back. Keep the lights on, because they cannot see well now and may be scared in the dark.

But in reality there is no way to be fully prepared. Here’s what I wasn’t prepared for:

I wasn’t prepared, in the hours before my grandmother’s death, for her to be the most beautiful person I had ever seen. I wasn’t prepared to push her white hair back from her forehead and notice that her skin and blue eyes were radiant, glowing—not with fever—but with something I had never seen before. That her hands and nails, reaching out to someone or something none of the rest of us could see, were perfect.

I wasn’t prepared for her to speak to her brothers and sisters, gone before her, asking them to come closer, to come back, to take her. I wasn’t prepared to stand outside with my brother and sister later, and see him with his square hands on his hips and see her red hair flash like a flame and think, I will call out your names when I am dying.

I wasn’t prepared for my grandmother suddenly to fix her eyes on me and say, “I want some candy,” then to lift my fingers to her mouth and suck on them, then lower them and say, “that’s better.”

Just as I was not prepared for any of this, I was not prepared for the storm to hit. The rain I expected—and it began early—but I wasn’t prepared for the wind, which tore through the trees, and made them bend until I was sure they would break. I wasn’t prepared for the sudden cold. I wasn’t prepared for the sound of it, the rattle and howl.

But, most of all, I wasn’t prepared for what came after: The sudden stillness. The deceptive quiet. As if nothing had happened at all.

There’s this game children play. One child takes another’s arm and tries to twist it painfully behind her back in such a way that she cannot break free. To be released, the captive must call out “Mercy!”

This game is about power—about one exerting brute force over another, demanding not only a confession of helplessness, but a plea for clemency. “Mercy” is not an expletive; it’s a request—a desperate one.

But there is another way to think about mercy, and that is as something rooted in love. A pardon, somehow, miraculously, from pain. And what’s granted is perhaps not even comfort, but another way out, one of mystery and awe.

When I was tossed into the deep I didn’t swim, but I didn’t sink either. I clung to a mercy that felt like neither punishment nor pardon. I think of it as a life raft, or, even better, a ship with many sails, passing other ships on separate courses that are headed, hopefully, to the same city.