Guest Post

Guest Post

By Stuart Scadron-Wattles

I recently gave a guest lecture for a graduate class on global development. I was told that I could do pretty much what I liked, and because it was a Christian college, I felt free to have them meditate on a particular scene from the New Testament, one that appears almost verbatim in three of the gospels. The account I chose was from chapter 12 of the book of John.

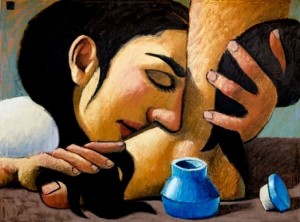

The scene begins with Jesus and his disciples at dinner in the house of Lazarus. The sister of the host, Mary, enters the room and begins weeping at the feet of Jesus, wiping his tear-soaked feet with her hair. Then she breaks open a vial of particularly expensive perfume to anoint them.

None of the guests like what’s going on. (We don’t find out what Jesus thinks until the end.) As John tells it, Judas protests at the cost of Mary’s act and points out that the perfume could have been sold and the proceeds given to the poor.

I asked my global development students to place themselves imaginatively in the scene. Where were they, I asked? What did they see or hear?

Three of them said that they were Judas, questioning the cost. Another said that he heard Judas laughing, yet another that he caught Jesus giving Judas a stern look.

As for me: I couldn’t stop thinking about Mary.

What was this woman doing, speechless with sorrow—tears dripping, sniveling with snot—wiping the filth of the road off of Jesus’ feet and using her own hair for a towel?

What possessed her to bring along a jar of perfume so costly that it was considered a superfluous luxury, and lavish it onto feet that were no doubt going to be both sticky and dirty five minutes after their owner left the dinner table?

It’s a foolish act. My students’ responses and the chronicles of those present say as much.

Then it hit me: Mary’s act is like that of an artist.

What is she doing if not making art: carrying her human sorrow for the world, crying for the futility of it all, lamenting that the beloved should need to descend to this broken, dirty place.

And perhaps hoping against hope that she could do something beautiful—or at least cleansing—with those tears, if only for a moment. She uses her own sorry self to try to make it better, her most expensive treasure to get it to smell right.

She doesn’t even know if it will do any good, she just knows that she needs to do it.

This has all of the attributes of art-making.

As artists, we like to think that we have an audience, a readership. Those of us who are professionals depend upon the commercial transactions around that relationship for our livelihood.

But Mary is doing this without regard for her audience. She is in the presence of the beloved, and that is where, if we are honest about it, we make our best art: the work that is useless to the world, wasteful of our resources. Proceeding as it does from that dark, mysterious place in our souls, it can often positively drip with embarrassment.

It is the act of a fool.

Nothing will be made better by this act; no meaningful dialogue took place in that room. This is an encounter between the Fool and the Beloved. In all three of the gospel accounts, Jesus never speaks to her.

In the middle of this encounter (or more likely towards the end) Judas decides to drag in some helpful comments about the poor, by way of adjudication and evaluation. His response is itself critiqued by the narrator. John breaks from his story and in the process betrays his own judgmental attitude, questioning the motives of Judas’ criticism.

Mary’s piece of performance art apparently cannot stand on its own. It requires two critical responses, neither of which helps us to engage with the act itself.

That said, I am grieved by Judas’ use of the poor in order to evaluate a wasteful, creative act: not because of his motives, but because he is trying to make us more comfortable with the scene—by dismissing its significance.

We’re more comfortable—less embarrassed—with Judas’ very contemporary assessment. The woman is excessive; she does not exhibit sufficient Christian wisdom about the value of things and the importance of the poor.

If the value of money at work is its highest good, Mary’s act is indeed a poor investment, possibly a worthless one.

Judas knows what Jesus is about to say, that we will always have the poor with us, and since they are right at hand, he can readily haul them in. But his use of the nameless, faceless poor is a dishonest, manipulative move that draws the narrator and then us away from the feet of the beloved, where the real action is.

Continued tomorrow.

Stuart Scadron-Wattles has written his way through music, professional theatre, and intentional Christian community. He currently lives with his wife Linda and extended family in Seattle, WA, where he serves as director of resource development for Image.

Accompanying image: “Anointing His Feet” by Wayne Forte, oil and acrylic on canvas.