Part Three: Standing Before a Painting

Guest Post

By Daniel A. Siedell

A painting is more than meets the eye. And yet, it meets our eye. How are we to respond? Unfortunately, we’re conditioned by museum curators to do all we can to avoid this encounter that puts us in the crosshairs of that paint-smeared canvas.

I should know—I was one of those museum curators.

We mean well, but we rush in to break up the confrontation that looms between you and the painting. We do it under the guise of education. We tell you that before you can look at this or that painting, you need to know something about the artist and her life story and philosophy, you then need to learn something about the time period, about the style, and about a dozen other things that art critics, curators, and art historians write books on, but really, when it comes right down to it, drive you away from rather than toward the painting.

After we’re done, you see the painting only as an historical artifact, a journal entry, a visual illustration of what you’ve been taught. And you leave the tour of the exhibition knowing something about the artist, her life, the time period, and art history.

You’ve left without actually listening to the painting. A curator friend once said that the problem with didactic labels in a museum exhibition is that people read them.

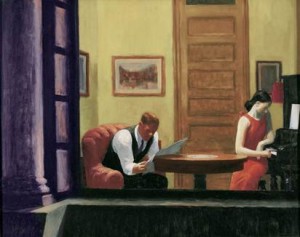

But let’s return to that painting that stands before you, calling at that moment. Consider Edward Hopper’s Room in New York (1932), a painting in the permanent collection I oversaw for over a decade. It is one of the most valuable and historically important paintings in the collection, and a pilgrimage attraction for many.

How do we receive it? We begin by allowing the painting to unfold, gradually. We notice there are two figures in an intimate and quiet setting. We recognize that they are not communicating. We also notice that we are voyeurs, glimpsing them through an open apartment window in an urban environment.

But that is not all. Gradually we become aware of a feeling the painting produces. The figures are close physically, connected by the table between them, but they are miles apart psychologically. One seems distracted, wanting to be noticed. The other is content, absorbed.

The relationship is unbalanced—one must chase another. Is this a one-time feud, or is it, as it seems, how the relationship between the two is played out daily? Perhaps we feel the thick tension of silence, what should be a retreat from the tension of the city becomes its re-enactment. This home is not safe. Do we feel suffocated, tight, claustrophobic, perhaps?

But Hopper doesn’t accomplish these feelings in us through the figures. That green wall is strange, isn’t it? It pushes into our space, shrinking the depth that the apartment window produces. The door, too, seems to push forward as well. The border of the window that frames this scene, creating a painting within a painting, flattens out the surface.

If we think about it, the indescribable green wall, prominent door, and window frame, the sharp vertical and horizontal lines contribute at least as much to the feeling we are experiencing as the figures themselves. And if we look at the figures closely, they seem to dissolve as paint strokes into the wall behind them.

The emotional impact the painting has on us, however, emerges because of our own lived experience, of isolation, of quiet desperation in an unbalanced relationship, or it reminds us of a scene in a movie or a novel, or we call to mind a line from a poem by Emily Dickinson or Robert Frost. The painting activates our memory, which St. Augustine so poignantly called, the belly of our mind.

Now, all of a sudden, we are not reading the painting, it is reading us.

And remarkably, not one word has been said about the artist, his influences, his worldview, his style, historical period, historical significance, or even how much the museum paid for the painting in 1934 (several hundred dollars) and how much it is worth today (many millions).

Edward Hopper did not paint the painting to reveal to you his thoughts, his influences, his historical epoch. He didn’t even paint the painting as a “story.” He painted the painting as a moment that unfolded in us a particular feeling, an experience that is simultaneously strange and familiar.

The “education” that we museum curators, art critics, and art historians provide undermines the integrity of a work of art if it does not attach itself to and build on the initial experience or feeling it engenders in the viewer, speaking to our experience in surprising ways.

For that is what painting is. This is exactly what the literary critic George Steiner meant when he declared that we must let the work of art have the run of our inner chambers, to let it go into those regions of heart and mind we hide to reveal what we didn’t even know existed.

No matter when a painting was made, its intended audience is the one who stands before it. This is why the Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko once lamented that it is a risky business to send a work of art out into the world, for someone else, for you and for me.

As I hear from friends whose paintings were destroyed by Superstorm Sandy last week, I am reminded just how risky it is to send a vulnerable thing like a painting out in the world, and such an act of grace to have the courage to do it.

And such a precious gift for us to stand before it, and listen.

Daniel A. Siedell (M.A. SUNY-Stony Brook, Ph.D. Iowa) is on staff at Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church in Fort Lauderdale where he is curator of Liberate, the resource ministry of Tullian Tchividjian. He is the author of God in the Gallery (Baker Academic, 2008) and numerous writings on Christianity and modern art. He blogs weekly at Cultivare.