Troubling me.

It hurt me and aroused my sympathy for that boy, that young man, the Reb’s firstborn son being groomed to replace, one day, his father as head of a Hasidic dynasty.

A father who tested this son, his future, his sect’s future, every Sabbath afternoon before an audience of devoted followers. They looked with awe on their rebbe and his son, their future leader, who never failed to catch the mistake his father would slip into the lesson he offered from the head of the table around which men and boys gathered for a light meal, the mystic’s meal, for at that hour they had little need for physical nourishment. The Sabbath’s waning hours: by then the faithful were nourished almost entirely by the soul.

And when he wasn’t teaching and testing his son? Reb Saunders would not speak to Danny, not a word to his brilliant, beloved son.

Reb Saunders’ inexplicable, unbroken silence seemed cruel to me. It seemed cruel, too, to Danny’s dear friend, Reuven Malter.

As I turned the pages of Chaim Potok’s The Chosen: sympathy for Danny, irritation at his father. Or was the irritation at myself, a reaction to not being able to understand Reb Saunders’ behavior?

Have you heard this one? “The tzaddik sits in absolute silence, saying nothing, and all his followers listen attentively.”

Tzaddik: righteous one. Rabbi Arthur Green writes that in Jewish life, one attains the title of tzaddik “primarily due to acts of extraordinary generosity and selflessness within the human community.”

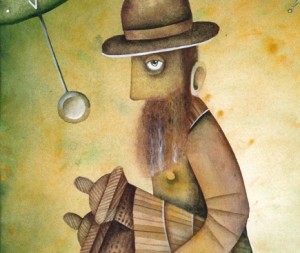

I can see a New Yorker-esque cartoon in which a group of bearded men in black caftans crowd around their rebbe’s Sabbath table, one disciple squatting under the table hoping to catch some crumbs from the holy man’s plate. At the head of the table, their rebbe, his eyes closed, in a near trance, strokes the inverted, sour-cream streaked flames of his beard, feeling for wisdom, drawing it into his fingers, from there to flare behind his heart, illuminating it, all the while his lips tremble as if about to form a word, just one word for which his disciples ache, one word to release them from ignorance and suffering into God’s love.

As if he had been slapped by the joke that Ruben, who had heard it from another student, passed on to him, Danny’s “face froze.”

Then, for a long moment, Danny “said nothing.”

Speech: a bridge over the gap dividing one person from another.

Really? The distance between us, you and me, is, if not closed, narrowed by these words? Or will the yawning gap never be closed, no matter how skilled I am at choosing words to say what I mean, the only thing I ever mean when I speak or write to you: I am alone. I am afraid in this room, this city, in this worldwide web, in this expanding universe.

Or, speech: clothing, costume, armor. A way to protect or hide one’s self.

In Genesis, when Adam and Eve discover they are naked—exposed, vulnerable—they cover themselves. Thus, they imitate God.

How? In Genesis One, God speaks: Let there be… But before God’s opening act?

Before speech, was God exposed and vulnerable, even terrified? To clothe and protect God’s self: is that why God creates speech before anything else? To protect God’s self, and to project an image, merely a part not the whole, of God’s self?

A people of the book, we admire it, we dwell on it, God’s speech (written down), nouns, verbs, even the shapes of the letters: God’s clothing, its pleats, its seams, its stitching, the fabric from which it is sewn.

Season after season: Reb Saunders’ refusal to speak to his son, other than of Talmud, his raw silence, an exposed wound.

“The tzaddik sits in absolute silence, saying nothing, and all his followers listen attentively.”

“For a long moment, [Danny] said nothing. His eyes seemed glazed, turned inward.”

Who knows one? One God. Who knows two? Two Tablets. Who knows the value of turning one’s gaze inward?

“Then [Danny’s] face relaxed. He smiled faintly. ‘There’s more truth to that than you can realize,’ he murmured. ‘You can listen to silence, Reuven…and learn from it. It has a quality and a dimension all its own. It talks to me sometimes. I feel myself alive in it…. It doesn’t always talk. Sometimes—sometimes it cries, and you can hear the pain of the world in it. It hurts to listen to it then. But you have to.’”

Like silence, sometimes words reveal; sometimes words heal, repair, make whole.

Late in the novel, Reb Saunders explains his silence.

Already when Daniel was four-years-old, Reb Saunders saw that his son was “a mind in a body without a soul.” “A heart I need for a son, a soul I need for a son, compassion I want from my son, righteousness, mercy, strength to suffer and carry pain, that I want from my son, not a mind without a soul.”

“A tzaddik…must know of pain. A tzaddik must know how to suffer for his people,” Reb Saunders explains to Reuven.

“Words are cruel…they distort what is in the heart, they conceal the heart, the heart speaks through silence. One learns of the pain of others by suffering one’s own pain…by turning inside oneself, by finding one’s own soul.” Reb Saunders learned this from his own father, who taught his son, his successor with silence.

Destruction of the Temple, expulsion from Spain, pogroms, the Holocaust, and, since the creation of the modern State of Israel, suicide bombers, occupation, blockade: are we minds in bodies without souls? How else to explain it—God’s silence, our companion throughout history. Meanwhile, we pester God with prayer.

There is more to say about silence. For instance, this: