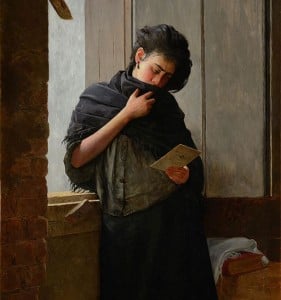

I’m told there are words in Romanian (“dor”) and in Portuguese (“saudade”)—those two outposts in the geography of romance languages—that cannot be easily translated. The concept is a combination of longing, yearning, loving, and missing, wrapped up within melancholy and/or nostalgia, but not exactly any of those things and more precisely all of those things and then some. To see the consternation on the faces of native speakers when they fail at trying to put the idea into words is testament enough that there are some realities for which there are no easy conversions.

I’m told there are words in Romanian (“dor”) and in Portuguese (“saudade”)—those two outposts in the geography of romance languages—that cannot be easily translated. The concept is a combination of longing, yearning, loving, and missing, wrapped up within melancholy and/or nostalgia, but not exactly any of those things and more precisely all of those things and then some. To see the consternation on the faces of native speakers when they fail at trying to put the idea into words is testament enough that there are some realities for which there are no easy conversions.

Of course this does not mean, as only the silliest of linguistics students likes to parrot, that the hearts and minds of those peoples are deeper, larger, and more poetic than ours. It just means that a concept we are fully capable of experiencing ourselves has never been uniquely nominated in our tongue. Why that’s the case, I don’t know; English has its own set of peculiarities and untranslatable ideas.

But the point I’m interested in is the juxtaposition of love and sadness. Here’s my theory:

- Love is transitive.

- As such, love requires an object to spend itself upon.

- If the object of love is removed, the current is blocked, dammed.

- That blockage results in pain.

- That pain we call sadness.

Therefore, love that can no longer be fulfilled, due to the death or departure of the beloved, creates the fugue state with which we are all too familiar. The blockage of love refused—its rejection, amounting to what was formally called unrequited love—creates the same kind of pain. Similarly, love that never finds a repository also creates this condition, which is the kind of hurt caused by an expectation that never comes to be. Perhaps on the continuum, disappointment is the gentlest form of sadness.

The natural model for this standard is human love, but the love—requited, unrequited, or unfulfilled—of a certain place, or of a type of labor, or of a set of circumstances, or even of an animal, can work just as well to make the point: sadness is no more or less than the frustration of love’s existential need to release itself, whatever might serve as the cause of that frustration. The degree of pain felt is roughly proportionate to the volume of the channel blocked.

Sadness might be profitably distinguished from grief, a term that I would reserve for a different kind of pain. While sadness follows grief, and might sometimes be characterized as a diffusion of it, grief is the physical registry of the violence to the psyche caused by the disruption of losing love’s object. The abrupt, ragged tear in the fabric of our existence that we experience in grief manifests in turns of stunned amazement, incredulity, fury, and the physical agonies of breathlessness—as though one has fallen from a high place—thirst, incessant swallowing, insomnia, muscular tension, and aridity that is not unlike the sensation of starving; tears are the least of it.

Another metaphor for grief would be the adaptation throes of one brought too quickly from a native environment into another, foreign place, such as a jungle dweller dropped into a desert, or a river man transported to the Pyrenees. The mind as well as the body recoils at such a thing, deprived not only of what it has known, but of what it has always seen and counted upon. The adjustment is a tortuous process.

Sadness, on the other hand—though often a diffusion of grief through time, as has been admitted —expresses itself metaphorically as a type of cloud, a grayness, a mist. It is said to descend upon us in fog-like fashion. Grief is by far more physical than sadness; one is said to be “beside herself” or nearly “out of her mind” with grief.

Sadness is more cerebral. One stares, withdraws, reflects when sad. Walks are taken and sallies are made to jar the mind from thoughts that pull too hard, that push too far back. We need distractions from sadness, because we’re caught inside our heads with it. Sadness indulged too liberally can lead to the chronic state of depression and must be guarded against.

Even so, while it is a productive thing to find new objects for love after loss, once one of love’s repositories is gone, such a thing cannot properly be called a replacement. New channels of love can be created, but they are not the same channel, redirected. The beloved is unique, as it should be, and once gone, that particular flow is dammed. It is why sadness returns when something familiar, associated with the beloved, prompts the memory.

But there is something else in the kind of sadness that is not of the clinical variety, but of the common type that we carry with us for as long as we wander. It is a peculiar quality, with no word for it in any language that I know. I speak of the bittersweet aspect—that, but not exactly that—which ultimately vanquishes despair.

For there is an undertone of hope to sadness, at least it seems so to me. There’s a suspicion that it will not always be like this; most would say that there is a kind of sweet communion between the lover and the beloved, though the latter is gone, unseen, and an aura suggests, however faintly, that there is yet to be a reunion. About it all is a feeling that though what we experience is real—perhaps the greatest testament to love’s existence, in fact, is the registry of sadness—this longing is only transitory. The dam will one day break.

Perhaps the only way to express this is that in sadness there is a note of expectation, as slight as a fragrance that we cannot completely discriminate, or as elusive as a word for which we do not really have a name.

A.G. Harmon teaches Shakespeare, Law and Literature, Jurisprudence, and Writing at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. His novel, A House All Stilled,won the 2001 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel.

Image Used: Saudade (1899), by Almeida Júnior, oil on canvas, 77.6 × 39.8 in.