Has the Lord God graced us with any poetic mind as elegant and potent as that of his darling, William Shakespeare? No, I say, No!—thrice and four times, No! Fie upon it. Out, damned calumny!

Has the Lord God graced us with any poetic mind as elegant and potent as that of his darling, William Shakespeare? No, I say, No!—thrice and four times, No! Fie upon it. Out, damned calumny!

And don’t speak any garbage about him not really being him; nobody outside Bigfoot believers and Roswell Rosicrucians seriously contends it. He was him, all right, and a thrashing from crown to crow’s foot is owed to any villainous cur who repeats such bold and saucy wrongs.

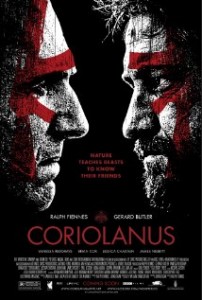

The occasion of my praise is to once again bring forth Shakespeare’s good, so that not for one second may it lay interred with his bones. So let it not be with God’s Will. For I have recently seen Ralph Fiennes’ film version of Coriolanus, the tragedy most beloved to those of a formalist persuasion (T.S. Eliot and company didn’t think much of Hamlet—they preferred Coriolanus; I disagree, but more of that anon), and it is a thing well made.

Coriolanus is about revenge—a favorite theme in Shakespeare—something all desire, all suffer for. Its power wields about indiscriminately, redounding upon the vengeful as often as it lands upon the victim—a bloody muddle of indignation, pride, and wrath.

In Coriolanus, we have a rapacious Roman war hero (Fiennes), the son of a lionhearted mother, Volumnia (Vanessa Redgrave). She’s like the Spartan women who sent their sons into battle, handing them their shields and saying “With this or on this,” meaning they’d either return from battle victorious, armed with shields, or dead, carried on their shields. Win or die.

But Coriolanus is a victim of the very thing that makes him what he is. Honor is his undoing. The Roman is a killing machine who cannot abide the company of his people. He is glorious on the field, arrogant in the court, and utterly unfit for the consular office others thrust upon him. To Coriolanus, diplomacy is craven, and he will not curry the favor of the rabble that he champions.

Then Shakespeare raises things a notch by showing the masses to be contemptible: The Romans are a boorish mob, as unworthy of credit as Coriolanus says. Their spokesmen, the tribunes, are despicable too; they crave power in the name of the “people.”

Everybody gets a coat of blackwash, but you don’t realize that at first. You’re all set to side with the common man, vulnerable to the populist pabulum they recite. A widespread mistake is to confound poverty and purity, as though hearts of gold reside necessarily in those who want. Of course, Shakespeare uses the error.

There are better lines in Will’s other plays, but when you’re talking about better lines in Shakespeare, you’re talking about white, five-carat diamonds compared to yellow, three-carat diamonds. One’s not as valuable, but we’re still talking serious jewels. And the greatest value comes by the power of compression—when a single line is packed with such tension that it drips like oil from an olive.

Here’s a sample:

Coriolanus to the mob, mocking their fickle support: “What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues; That, rubbing the poor itch of your opinion, Make yourselves scabs?”

Coriolanus rallying his troops, offering himself as their weapon: “O, me alone! Make you a sword of me!”

Volumnia venting her rage at Coriolanus’ banishment: “Anger’s my meat; I sup upon myself; And so shall starve with feeding.”

Look at those images—the counter-play, the inversion, the density.

Still, they aren’t quite equal to those in Hamlet, where exquisite lines are spoken within a disorienting theater-scape of metaphysical quandaries. We’re watching a play, yes, but we’re watching players in a play who watch a play too. If all the world is in fact a stage, and we . . .

Then, in a trice, the wall is behind us. We’re swept inside the drama like carnival-goers lost in a house of mirrors. We’re watching them, but who exactly is watching us?

We are asked: What is it to be? That’s a hell of a question all by itself. But then the questioning goes further: What is it not to be?

— ay, there’s the rub; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come; When we have shuffled off this mortal coil?. . . Thus Conscience does make Cowards of us all, And thus the Native hue of Resolution

Is sicklied o’er, with the pale cast of Thought.

The actions and inactions of both avengers, Hamlet and Coriolanus, undo them, playing not only upon questions of who we are and what roles we should take, but also questions of where we are and what all this playing means.

Further still: What is it to do, or to be, God’s will?

I’ll relate a little exchange with a student regarding Hamlet, to illustrate the payoff that comes when someone realizes for the first time what the old boy can do:

Him: But Hamlet won’t act.

Me: And that’s what you want him to do? Act?

Him: Yes.

Me: I’d say he’s an actor. But I guess you mean you want him to murder Claudius?

Him: Right.

Me: He kills Polonious. Isn’t that acting?

Him: That was by mistake.

Me: But wasn’t it acting?

Him: Yeah, but…

Me: And he sees that the traitors Rosencrantz and Guildenstern get what they deserve?

Him: Yes, but he draws back whenever it comes to Claudius. He won’t act there.

Me: He spurs the king’s conscience, doesn’t he, in the play-within-a-play? Doesn’t that act bring about some consequence? If he hadn’t acted as he did—

Him: But that play-within-a-play stuff is more about acting and the theater and double entendre.

Me: Yes. It’s acting. Hamlet acts a lot. He’s in a play.

Silence from him.

Him: Wait, so you mean—so when you say “act,” you mean—

Silence from me.

Him: Wait—what are we talking about here? Where are we?

A+, my son. A+.