Now that our son is almost ten, he has begun to feel his oats a bit: In the middle of fourth grade, he has begun to log a few life achievements that both we, and he, are proud: he has surmounted some of his attention problems and can stay focused on the tasks at hand—reading about military history, remembering to take out the trash, remembering to modulate his quick-start anger before it bursts from his lips.

Now that our son is almost ten, he has begun to feel his oats a bit: In the middle of fourth grade, he has begun to log a few life achievements that both we, and he, are proud: he has surmounted some of his attention problems and can stay focused on the tasks at hand—reading about military history, remembering to take out the trash, remembering to modulate his quick-start anger before it bursts from his lips.

He has also learned to complain about having to go to church. Sunday mornings in our house arrive drowsily and sun-soaked, the tendrils of smoke from the censer we always light curling up the stairs.

But by the time we are actually ready to walk out the door, between him and his little sister, it is all over but the shouting. In my daughter’s case, her complaints are minor, and classic: the ill-fitting patent leather shoes, her grumpiness at being told that taking a Bitty Baby stroller to the Divine Liturgy is inadvisable.

My son’s complaints are more subtle, and dangerous. Only occasionally will he trot out the old chestnut, “God is just an idea that somebody made up way back when,” because he knows that I know that at least for now, he doesn’t believe it: For any and all problems he has with God, I have seen him sincerely implore, and sincerely repent, before the invisible and ever-present altar of the Divine.

One of our dearest neighbors, a reader of this blog, has been in treatment for breast cancer these past six or so months, and when we say prayers at night, he always remembers to lift her name like a found jewel. And he was thankful when her chemotherapy regimen came to an end.

He also knows that, in these secular times—some of my best friends are atheists!—I would never respond to that claim in the way my own mother, lightly religious herself but steeped in Southern Baptist tradition, exclaimed: “The very idea! You ought to be ashamed of yourself.”

“Yep,” I say, casually. “Lots of people don’t believe in God. We do, though.” And while he may end up faithless later, he’s living in our house now.

At other times, my response won’t be a light one, but will instead be brimming with passion: Because of course there’s physics! The mysteries of evolution! The world is charged with the grandeur of God!

Believe it or not, the more complicated question is not about the existence of God, but about why it is important to go to church at all. My husband is Catholic and I’m a convert to Orthodoxy—neither of which are “just believe in your heart” kinds of faiths—but the question of why it is important to actually go to church seems to be the one that is more pressing, and relevant.

Let me tell you, when we are trying to get them kicking and screaming out of the door on Sunday morning, I have sympathy for anyone who decided that arguing about church attendance wasn’t worth it, and just decided to throw in the towel.

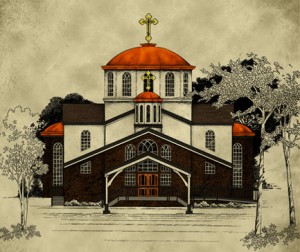

And sometimes it has involved literal kicking and screaming—out to and into the car, and around the Capital Beltway nearly twenty-seven miles from our house to the Antiochian Orthodox Church we attend in the Montgomery county suburbs. “Damn you,” I said one Sunday morning to one of my children, and I have shouted the F word, and punched on the accelerator while changing lanes.

If this were a movie, this would be the moment that would expose the yawning irony between my pious hopes and the less than beautiful reality of family life. “Shut up and worship the birth of Jesus Christ!” Christine Baranski’s character gripes (I’m paraphrasing) at her children on Christmas in the hilarious 1995 movie The Ref, and the implied take-away from that scene and similar scenes in other movies— would seem to be the essential hypocrisy of any kind of religious indoctrination.

What do these movies want, I wonder? I guess the “authentic” move at this point would be to throw the towel in and, what? Agree that, Yes, Mommy has been an inflexible hypocrite. Let us enjoy this Sunday morning with a walk in the park and a movie afterward. Be spiritual but not religious. You can decide for yourself when you grow up.

Well, too effing bad, I think. The notion that any of us is, or can be, anything other than a hypocrite, seems to be a legacy of good old American Puritanism, in its secular form: That by our ethics and good will alone, we can be perfected.

Instead, I am a sinner.

And as such I need more than the thought experiments of ethics and sentimentality. I need the Body and Blood of Jesus. You can’t get that anywhere else but church, I tell my son.

I have noticed that by the time we are halfway around the Beltway, their griping has stopped. After we have arrived at church, at last, the gold-touched dome with its cross scraping the sky looms over us as we shepherd each other inside.My son lopes away from me, off behind the altar screen where there are no girls.

Half of success is just showing up. My daughter and I light a candle.

When someone dies, we are served Kolliva, made of wheat berries and powdered sugar.

I am building an architecture of the invisible.

When and if they reject it, my children will still remember the Blood of Christ coursing through their bodies; their half-asleep noses will distinguish incense in their dark and dreamlike rooms.

That’s not nothing.

The colors of the icons will still shine, in the afterimages of their eyes.

A native of Yazoo City, Mississippi, Caroline Langston is a convert to the Eastern Orthodox Church. She is a widely published writer and essayist, a winner of the Pushcart Prize, and a commentator for NPR’s “All Things Considered.”