Continued from yesterday.

Continued from yesterday.

On the pleasant train ride from Florence to Venice, my wife Laurie and I began to piece together a relaxed itinerary for our final days in Italy: the Jewish Ghetto—definitely; the Peggy Guggenheim Collection—pretty sure; the Doge’s Palace—we should (but haven’t we had enough history?); the Basilica di San Marco, the Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari—haven’t we seen enough churches?

As it turns out, we did make it into a church (more than one) in Venice, but it was only at Santa Maria della Salute—a church on which we stumbled while rushing to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection so we could see it and have plenty of time for the famous Jewish Ghetto in Venice—where I felt the tenacious need to maintain my separate, external, egotistic will relax.

There was a prayer to be said and I said it in this church built to honor the Virgin Mary for saving Venice from a plague that in 1629 to 1630 killed 47,000 residents; a third of Venice’s population.

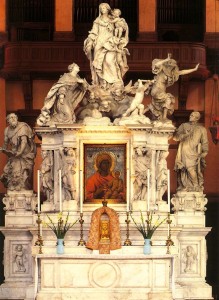

In the presence of the Madonna of Healing, my eyes fixed on the sculptures above the main altar, fixed on one sculpted figure in particular: a woman below and to the right of the Madonna, her body turned away from the Madonna, her arms outstretched beyond the “frame” of the sculpture, into the void, in anguish, afflicted, her neck twisted so she could look back and up at the towering Virgin holding an infant in one arm.

That’s human suffering. That’s the desperate cry for healing when healing, at least physical healing, may be, finally, unattainable.

“Mi shebeirach—may the One who blessed—the One who blesses—our patriarchs and matriarchs,” I sang quietly to myself, “bless those in need of healing.” My list: Sam, Cindy, Katherine, Ed, Sharon, in various stages of being ravaged with illness. “Bless those—bless these—with perfect healing—with whatever form of healing is possible—the renewal of body and spirit, and may the One who blesses help us find the courage to make our lives a blessing.”

To myself I sang the Hebrew, to myself the English, to myself I sang this contemporary interpretation of a traditional Jewish prayer for healing. In church I sang it. Maybe it’s more accurate, more honest to say, in this Catholic church, a church in all its particularity and also a sacred space—or space made sacred by artists and architects and culture and worshippers and the fullness of the human heart and spirit— in this space I was sung by a Jewish prayer, by a prayer whose vehicle I became, for though it wasn’t planned, it wasn’t on any itinerary.

Unbeknownst to me I had carried the prayer all the way to Italy to be offered here. And when it rose from my heart to my lips, I was a Jew and not a Jew, far from home and home.

When I was finished with the prayer, I rose from the bench and became a tourist again, a tourist delighted to see magnificent works of Titian displayed elsewhere in the church, delighted to wander sections of Venice where fewer tourists wandered, delighted to watch the Vaparettos come and go from Celestia station, just below the window of our modest apartment.

I don’t know who, if anyone, benefited from my prayer. I was certain none of those for whom I prayed knew they had moved me to pray. I wasn’t even certain that they had moved me to pray. Might it have been something else, some other force—the power of art in a place of worship? The feeling of helplessness as I thought about colleagues, friends, and family suffering from illnesses from which they may not, finally, recover?

Later that day, our trip nearly over, we sat on a quiet street beside a canal along which gondoliers plied romance for forty minutes and eighty Euros. We sipped our first Spritz Venezianos as the gondolas slid by just below us.

Even as we sat there, Laurie and I, grateful for beauty, history, privilege, each other, we were already composing the stories of our trip, stories that include a moment of easing out of our story to let God’s story be enacted and told in our hearts, before our eyes.

Richard Chess is the author of three books of poetry, Tekiah, Chair in the Desert, and Third Temple. Poems of his have appeared in Telling and Remembering: A Century of American Jewish Poetry, Bearing the Mystery: Twenty Years of IMAGE, and Best Spiritual Writing 2005. He is the Roy Carroll Professor of Honors Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. He is also the director of UNC Asheville’s Center for Jewish Studies.