“Those who love this world have eyes only for what pleases the flesh,” St. Stephen of Muret cautioned us. “Lust shuts up their spiritual senses, and so they pick what is worst for themselves.”[1] St. Stephen warned us that our attachment to the world, our seeking after the pleasures of the material world, forms within us one of the deadly sins, lust. The flesh, the material body with its passions when left unchecked can lead us into all kinds of intense longing which then permeates within our mind, interfering with how we think, how we act, that is, with how we live.[2] Giving in to lust creates more lust; even thinking about the things we lust after will help lust grow. Some initial act or thought of lust becomes the cause of more and greater lust. The more we let lust in our mind and affect how we think, the more it seeds itself in our life, in our mind, and it cycles itself in our head, causing a whirlwind of passions which can keep us trapped in a cycle of perpetual desire which cannot be satisfied.[3] Thus, Asaṅga, an important Buddhist explorer of the mind and how it works, explained, “If a person engages lust, he becomes permeated with lust. As his mind repeatedly arises and passes away in tandem with lust, the lust becomes the generative cause for the [lustful] evolutions of his mind.”[4]

While in the modern age lust is often connected to the pursuit of some sort of sexual gratification, it is not the only way lust can and does affect us. Craving attaches itself to the mind, keeping us attached to those things we lust after. It can be many things, each which can be limited but relative goods which can be good to receive if we do not overly attach ourselves to them. The problem always lies with our intention and how we treat such goods, as we turn them away from their proper good and into evils for ourselves. Our lust, therefore, can manifest itself in attachments to many things, some material in quality like money, food, books, clothing, or the like, but some are of a more intangible nature, like fame, glory, or power. We become, as it were, fettered by our desire, our will weakened by its effect upon us and our mind. So long we let lust and its attentions remain unopposed in our mind, we find it slowly encouraging us in our actions, suggesting those ways we can fulfill our desires. Indeed, as long as it permeates in our mind, it influences our thoughts, constantly suggesting ways in which we can satisfy our base passions which veil from us those things, those elements, which could hinder our pursuit. That is, not only does desire draw us in to those things we desire, it also averts us from those things, or people, who would work against the attainment of our lust, so that we see those things or people who could help us in a negative light. We often end up hating those who oppose us in the acquisition of our lust; we end up avoiding them, making it extremely difficult for us to overturn the spiritual trap which lust has sprung in our lives.

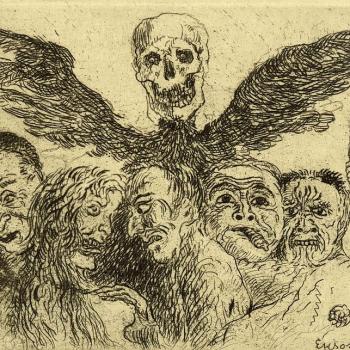

From what is seen with lust, from the craving which is manifest in it, we find that all sin, which really can be seen as a manifestation of inordinate desire for one thing or another, is the cause and foundation for other sins. The notion of the seven or eight deadly sins, found in early monastic and medieval spirituality, is based upon this concept – sin seeds further sins, and the deadly sins are deadly not only because of the gravity of the sin, but also because they help guide us further and further into a life of sin if we do not take them out of ourselves and stop them from producing their most deadly seed in our consciousness. Sin spreads itself in us like a cancer, and unless it is rooted out, it will slowly take us over, destroying us from the inside out. Sin if left to its own devices, will lead to spiritual death, to hell, where all we will have is the sin which covers us and our mind, leaving us unable to free ourselves from its prison of unfulfilled desires.

Sin darkens the spiritual eye of the sinner, so that their experience of the world is tainted by sin, for it acts like a lens in which the world is experienced. Thus, we can understand more how sin taints the mind of the sinner, keeping them in spiritual ignorance, forcing them to think and act and react, not according to the truth, but in accordance to the mental filter which is caused by sin. Sin not only causes us great pain and suffering, but leaves us lost in its wake, our mind deluded, our thoughts shaped by the logic of sin, as Pope Shenouda III, the former Patriarch of Alexandria, explained in relation to various parables of Jesus:

Yes, sin is loss, it is delusion and straying. The sinner is a lost person, whether he was lost by his will, or ignorance, or by someone else. When the prodigal son left his father’s house, he thought he had found himself and had found freedom, wealth, enjoyment and friends. In actual fact, he did not find himself, but lost it. The lost sheep might have felt that he left the small closed field for the empty wide open space. Finally, though, he found that he was lost and had departed from his shepherd and from his beloved. The sinner understands freedom and enjoyment in a wrong way. In the same way in which he thinks that sin is victory, it becomes a defeat for him.[5]

As long as we continue in sin, we have a very difficult time seeing it and its effects on our lives; it lies hidden, deep within, indeed, confused by our minds as being a part of who we are, so that we fight for the preservation of sin as if we are fighting for our very lives. It is a parasite which makes us think it is a part of ourselves; it helps us construct a false view of the self which includes such sin as a part of our very character. And yet it is not; once we have overturned its influence, we can look back and see how easily manipulated we were by it. “It is only when you have finished with a fault that you notice it. It is like living in darkness; until you have emerged from it, it is imperceptible.”[6]

We tend to think we are free entities in the world, free to choose what we would like to do. But as long as we sin, this is not the case. Sin infects us, hiding its structures and patterns of thought in our very consciousness, binding us to its dictates while giving us the illusion of freedom. Sin hinders our ability to see and understand what we have lost once we have given in to its dictates, for it darkens our mind and spiritual senses, so that we cannot perceive that which we have lost – thus without knowledge of what true freedom its, its sham imitation is easily accepted as the real thing. It is for this reason Jesus warned us, if we want true freedom, we must keep our spiritual eye pure, clean from sin:

Your eye is the lamp of your body; when your eye is sound, your whole body is full of light; but when it is not sound, your body is full of darkness. Therefore be careful lest the light in you be darkness. If then your whole body is full of light, having no part dark, it will be wholly bright, as when a lamp with its rays gives you light” (Lk. 11:34-6 RSV).

This, moreover, should help us understand what Jesus meant when he said that we should not judge someone while we are still infected with and tainted by sin ourselves:

Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, `Brother, let me take out the speck that is in your eye,’ when you yourself do not see the log that is in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take out the speck that is in your brother’s eye (Lk. 6:41-2 RSV).

Our sin should be our focus. If we truly want to help others, we should over turn sin in ourselves first, so then we can look to them not out of our sin, filled with hate and rage, but in love and help them, not through judgment seeking their condemnation but with compassion. Once we have overturned sin in ourselves, we will know not only its full effects, but also, what best counters it. Until then, though we might have the best motive in mind to justify the condemnation of the other, it hides a deep rooted sin in ourselves and such judgment just acts as a scapegoat mechanism in order to prevent us from dealing with our own sin. It is just another way in which our sin blinds us, and the more we ignore our own sin, and do not cleanse ourselves from it, the more we will see and experience the world in and through sin, as a kind of spiritual cataract, so that not only do we condemn the other unjustly, what we end up condemning is a projection from within more than anything else.[7] “The doctor who cannot cure himself is not the most suitable to treat another. The hypocrite’s evil eye is wide open to see other people’s faults, but cannot see his own failing.”[8] Indeed through our self-made spiritual blindness we end up judging others, not out of love, not for their greater good, but to help ourselves feel superior over them. Or, when we are truly trapped by the logic of sin, our judgment comes out of pure hate, and our sin forms an unconscious desire to hinder someone else in their own spiritual quest, to prevent them from being our superior (for we would be envious of them if we saw them transcend us and became better than us):

Do you see, that He forbids not judging, but commands to cast out first the beam from your eye, and then to set right the doings of the rest of the world? For indeed each one knows his own things better than those of others; and sees the greater rather than the less; and loves himself more than his neighbor. Wherefore, if you do it out of guardian care, I bid you care for yourself first, in whose case the sin is both more certain and greater. But if you neglect yourself, it is quite evident that neither do you judge your brother in care for him, but in hatred, and wishing to expose him. For what if he ought to be judged? It should be by one who commits no such sin, not by you.[9]

It is, again, sin which causes us to look out at others and judge them unjustly; sin justifies itself under the guise of some good. But in the end, such sin seeks to keep us trapped in thinking ourselves great when we are not, and to do that, we must find a way to think less of everyone else:

Self-love and high opinion of ourselves give birth in us to yet another evil which does us grievous harm; namely, severe judgment and condemnation of our neighbours, when we regard them as nothing, despise them and, if an occasion offers, humiliate them. This evil habit or vice, being born of pride, feeds and grows on pride; and in turn feeds pride and makes it grow.[10]

Our mind, therefore, becomes more defiled the more we sin; for the more we sin, the more sin seeds itself and permeates the mind, so that we find sin is both the cause of more sin:

Its defining characteristic is that, relying on the permeations of all defiled states, it is the basic repository of seeds whereby the arising of those states is maintained. Its characteristic as cause means that this consciousness with all these seeds is the cause for the constant generation of those defiled states. Its characteristic as result means that this consciousness arises as the result of the beginningless permeations of these various defiled states.[11]

And this, then, should help us to understand the damage done to us by sin. It keeps us deluded, ignorant of the truth. As it filters in our mind, seeding itself in our lives, it does everything it can to make sure we do not turn against it. It hides itself deep in our mind, in our consciousness, causing it to appear a part of who we are. And whatever shadows it produces in the mind, it seeks to project upon our vision of the world, to confuse our internal spiritual decay for something outside of ourselves, making us act and react, not according to the real problem, the sin which is deeply rooted within, but in the apparent sin of others, making us fight them harshly so that we do not do the real work of overturning sin within. Certainly, out of compassion and love, we should not neglect the needs others have, but the focus should not be in judgment of them, but in judgment of ourselves – we can only put ourselves to the cross, and let the seeds of sin, and the false self the constructed for us, be taken by Christ to be deposited into the depth of the abyss where they are placed, that is, in the everlasting fire of hell. [12] Thus, we find, salvation is detachment of sin, while perdition is attachment, the seeding of sin so deep in our mind, that in the end, it is all we know, inside and out, and all we experience, then, is the wreck of sin in our own private little hell. Anything which would keep us locked in, even apparent goods, will be used by sin to keep us trapped in its clutches. This is why, in the end, we must learn to let it go, to let it go before it is too late…

[1] Stephen of Muret, Maxims. trans. Deborah van Doel OCD (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2002), 166.

[2] While we usually think of lust solely within the confines of sexual desire, because of a very long standing use of the word, lust originally extended to all forms of inordinate longing or desire. We still get hints of such applications for the word in various phrases which remain in use, such as when we say someone has a “lust for power.” The phrase is not being used metaphorically, but rather, it is engaging the wide range of meaning containing within the word “lust.”

[3] The greater the desire, the greater the passion, the more we seek, the more we gain, the more we find that what we attain does not satisfy, causing us various forms of displeasure or suffering. Once that happens, we either reconsider our pursuit and put a stop to the cycle formed by such desire, or we think the problem is that we have only gained too little of our desire and the solution is to attain more and more of it until we are satisfied with what we have received. Since such desire over transitory goods will never satisfy, the cycle will never end unless we put a stop to the pursuit itself.

[4] Asaṅga, The Summary of the Great Vehicle. trans. John P. Keenan (Berkley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 1992), 21.

[5] Pope Shenouda III, The Life of Repentance and Purity.http://www.amazon.com/Life-Repentance-Purity-Pope-Shenouda/dp/0881415324/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1457444901&sr=8-1&keywords=shenouda+life trans. Nabil Guirgis (Sydney: C.O.P.T., 1990), 49.

[6] Stephen of Muret, Maxims, 58.

[7] Just as cataracts make us see things which are not there based upon what clouds the lens of the eye, so our spiritual cataract makes us see in others what is found in the lens of our spiritual eye.

[8] St. Anthony of Padua, Sermons for Sundays and Festivals. Volume II. trans. Paul Spilsbury (Padua: Edizioni Messaggero Padova,2007), 100-1/

[9] St. John Chrysostom, “Homilies on the Gospel of St. Matthew” in NPNF1(10):158.

[10] Unseen Warfare: Being the Spiritual Combat and Path to Paradise of Lorenzo Scupoli. As Edited by Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain and Revised by Theophan the Recluse. trans. E. Kadloubovsky and G.E.H. Palmer (London: Faber and Faber, 1963),141.

[11] Asaṅga, The Summary of the Great Vehicle. 21. The “beginningless permeations” of sin can be seen as another way to understand original sin, to see how sin cycles itself throughout history, going far back into the past which we cannot see, and continuing to be passed down, generation after generation, as our own personal sin is shown to affect not just us, not just the society we live in, but our progeny as well.

[12] As long as we remain attached to the seeds of sin, we shall follow with them into the fires hell; if we give them up, then that journey becomes our purgatory but if we never let them go, then, alas, we hold onto our sin to our own perdition.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing