When we grow up, the ways in which we interact with the world change. The eyes of a child look at the world in a different way than the eyes of an adult. Children tend be more trusting and believe with a simple faith what they have been told. As they grow up, they begin to test all things, finding many of the things they believed were false, and so end up being less trusting of others. Often, they become cynical and end up discounting everything they once believed, assuming it was all false. They think back to childhood as a time of pure ignorance, and so what was believed as a child must be seen in the light of their new “rationality,” their new perspective, which questions all things. And so they end up in a state of skepticism without knowing how to get beyond the deconstruction of the past with a reconstruction that takes them forward. They end up thinking such deconstruction is the only way they can be reasonable, and so they continue with their constant negation of all beliefs, using equivocation and false analogies to deny all beliefs which they end up labeling as “childish.”[1]

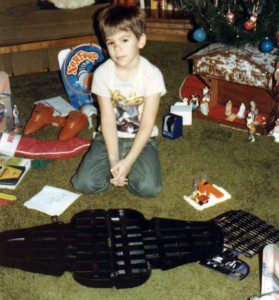

In this fashion, we often see critics of religions labeling religion and its teachings as childish, full of make believe like a childhood fantasy. They like to point out “fairy tales” children are taught to believe in, like Santa Clause, the Easter Bunny, and the Tooth Fairy, and say that religion is the same. Once you see through “Santa Clause,” you see through all religion – it is all make believe. Of course, the analogy is false – it is possible that religion is like that, but for them to make that claim they have to prove all religion is that way, and to do that, they have to go beyond skepticism and actually engage and promote truth claims of their own but without offering the proof needed to affirm such a teaching. We should certainly denounce as false what is proven to be false, but that is not what they do; they begin to assume too many things, connect many things in an erroneous, equivocal fashion, and end showing that the childishness they thought they left behind remains, and indeed, has become greater because they engage the world and religious beliefs, not through solid rational analysis, but in and through childish tantrums against truth claims they do not want to believe. They confuse all mistakes in belief to be the same, and do not understand that childhood beliefs often are not wrong, but rather incomplete and imperfect. As we grow and mature in our understanding, we should grow in affirmation of truth and let more of it in instead of discounting everything as they do. Certainly beliefs which need to be purified by reason should be, but that often means, not a total elimination but a transformation of those beliefs – understanding how what was taught to a child was taught in a form a child could understand (similar to the way mathematics is taught, and higher forms of mathematics transcends and contradict elements of mathematical thought taught early on because children would not understand what higher mathematics teaches without first understanding the basics).

Asaṅga in the Bodhisattvabhumi provides an important counterpoint to the skeptic, showing how their deconstruction of childhood beliefs can lead them further away from the truth than the beliefs they held as children.[2] He suggests we consider a young child, perhaps the son or daughter of a king or an influential civilian, who is raised up inside his or her home, and so has a limited perspective of the world. His or her parent buys a toy, perhaps of a cart with a deer, an ox, a horse, or an elephant, which the kid plays with and enjoys, never seeing and encountering a real deer, ox, horse or elephant. As such, the child believes his toys are real deer, real oxen, real horses, or real elephants. Then, as the child grows older, his or her parents tell him or her about deer, oxen, horses, and elephants, describing them and what they are like; the child, because of its experience, thinks his or her parents are talking about his or her toys because his or her experience is only with the toys which he or she had, and as a child, had imagined to be the real things. Eventually, the child’s parents take him or her out of the home, and show him or her real deer, real oxen, real horses and real elephants. At last, the child understands –and realizes what he imagines to be the real thing were not, but this did not mean the real things did not exist:

After seeing those [animals], this time [the son] gains for himself a genuine understanding. Then he becomes embarrassed for his previous conviction and reflects to himself: “These are the real deer-carts that my father had been describing to me for such a long time,” and so on, up to “[These are] the real elephant carts [that my father had been describing to me]. However, I had [mistakenly] developed the firm conviction [that he was talking] about those unreal objects, which are mere imitations, mere representations and semblances [of real carts].”[3]

Childhood beliefs are, therefore, often based upon true things misidentified and misunderstood with some representation of them which are over-literalized and made absolute. To say that the identification was wrong proves all the objects of belief held by children are false would actually undermine the way children learn and adapt and develop their understanding of the truth. What we find, therefore, would be as if people said, “I played with toys of animals which I have not seen, and I now know toys are not real, therefore the animals which were turned into toys are also not real.” But of course, as Asaṅga showed us, toys, which are not real can and often are made of real things, and just because a child confused the toy for the real thing does not mean the real thing does not exist and so the belief in such things is wrong. The same, moreover, is to be said about the myths and “fairy stories” told to children – the literal interpretation of the story might not be factual, but contained in and through them, are all kinds of transcendent truths which children learn and later, as they grow and become adults, learn the proper identification of those truths. It is not lying to children, just as it is not lying to children to play with toy elephants and pretend they are real elephants. What we have is that the form in which the truth is demonstrated differs for children and for adults. The skeptic who deconstructs all beliefs err in their judgment, because they would end up saying the toys, being false, mean the animals likewise must be false.

This should help us appreciate even more the meaning contained of St Paul’s famous words:

When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became a man, I gave up childish ways. For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood (1 Cor. 13:11-12 RSV).

We are still growing in our understanding of the truth, and as we do, we begin to understand the words we use to express it better. When we come face to face with the fullness of truth without any obscurations to our vision of the truth, then all of what we believed and understood will be shown to be true – but in a way similar to Asaṅga’s child who encounters the prototype of his or his toys; we will understand how the words pointed to the truth, and therefore were correct, and yet the truth transcends all the words and thoughts we had so that they are mere resemblances of the truth instead of the truth itself. The truth is found in and through them, just like animals could be understood in and through their toy counterparts, and yet – just as the real animals transcend the toys, so the truth which we are to receive will transcend the representation we have made of it all our lives. We are not wrong to believe as we do so long as we keep this caveat in mind. It is the caveat behind all truth claims, which, alas, the skeptics do not understand, and why look at truth claims, not as the adults they claim be, but like immature adolescents who want to throw away the toys of their childhood and think that is what it means to be an adult.

[1] Of course, they do not realize how much faith they rely upon for their own argument such as: faith in themselves, faith in their reasoning abilities, and faith in what they believe the rules of logic dictate. Some, to be sure, also add a new faith – a radicalized empiricism, though some do realize the self-contradiction of that position and keep to a pure skepticism which denies all knowledge of truth.

[2] See Asaṅga, The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed Enlightenment. trans. Artemus B. Engle (Boulder, CO: Snow Lion Press, 2016), 460-1.

[3] ibid., 461.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing