Mary’s personal freedom from sin, as seen in both her sinless life as well as in regards her immaculate conception, remains one of the most controversial aspects of Marian theology. For some, such as with the Orthodox, the controversy is more apparent than real, and comes more out of miscommunication than it does with any real dogmatic disagreement.[1] For others, such as with many Protestants, the denial is pure, and not just a miscommunication, although it usually comes without any real understanding as to why the teaching is taught nor as to how it is interpreted or understood by Catholics.

Because of their rejection of the teaching, some Orthodox and many Protestants, think they can prove it wrong by asking what they believe are impossible questions to answer except by denial of Catholic teaching. They are, for the most part, founded upon the premise that Scripture indicates that Mary, like everyone else, was a sinner. Did not St. Paul declare, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom. 3:32 RSV)? And did not Mary herself indicate this to be true of her when she said, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior” (Lk. 1:46-7 RSV)? Why would she say God is her savior if she is herself sinless? Does that not end up being a contradiction?

Nonetheless, when a proper theological examination is made concerning the holiness of Mary, these questions do not end up being as difficult as they first appear. For most of them, the answer is related to who she is and how she acts with God, in perfect harmony with God, throughout her life. Secondarily, there are also exegetical concerns, where a proper reading of Scripture, understanding how rhetorical flourishes are used by its authors, is also necessary.

Thus, the answer, for example, to questions related as to how God is said to be her savior if she is sinless is simple. It is because of the grace of God in her life that Mary was able to live a life of perfect human holiness. Grace perfects nature, allowing it to reach its full potential. Mary’s nature, like all human nature, was good, for all that is created by God, insofar as it keeps to the nature given to it, is good.[2]

Mary, unlike us, did not suffer the effects of sin, and so did not suffer, in her person, any diminution of her nature.[3] Sin makes us abandon our good nature, and so in and through our personal mode of being, become less than natural in what we do. For when we find ourselves in a state which is less than natural, we no longer have with us the full power or potential which was given to us in and by the nature God gracefully rendered to us. Once we have fallen into sin, we no longer can fulfill our potential in God because we have closed ourselves off from him. Therefore, as a result of sin, we find ourselves incapable of doing that which God desires us to do, for that would require us to live out and achieve our natural potential, a potential we no longer possess in our person thanks to sin. Thanks to grace, thanks to the forgiveness of sins, we can be raised back up and find ourselves restored to our original nature, to the good and potential we possess in and through it. When we turn ourselves to Christ, through him we are brought back to communion with God, open to him and his grace, and ready to be directed by him and follow him wherever he should lead. To follow that lead requires us to continue to be open to grace, to let it continue to penetrate us in our communion with God, so that we find that grace not only heals us from our sins but gives us perseverance against further sin.[4] That is, when we find someone does not sin, though no healing grace is needed to overcome the damage done by sin, grace continues to be in effect, giving them what they need in order to be able to preserve themselves from sin.[5] Thus, when someone does not sin, they have opened themselves up to God and his grace, and it is his grace which allows them to remain without sin, and so in and through that grace, God is able to be said to be their savior, saving them from sin. [6]

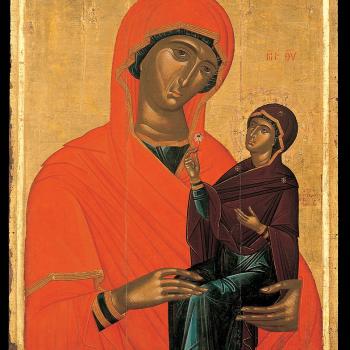

Mary, the humble handmaiden of the Lord, proclaimed with full humility that God was her savior. She knew in the fullness of her spirit that she would be nothing without his grace. She knew God not only as her creator, but also as her preserver in the world as well as the goal of her life (by entering a loving union with him in eternity). She was given an extraordinary role in creation, chosen to be the Mother of God, though it was a role she had to freely assent to in order to fulfill that role. And that meant she had to be entirely free, without the taint of sin, with no loss of liberty in her that would prevent her from giving a full and total surrender to God’s will. Thus, the preservation of her grace, in and all her life, was a precondition for God becoming incarnate in her.

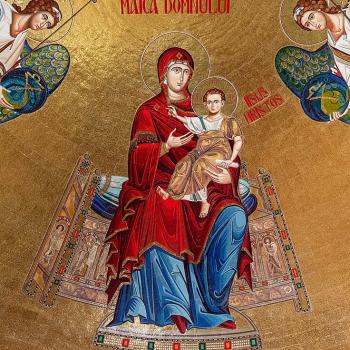

We find confirmation of this by the words of the Archangel Gabriel, who, upon meeting with Mary, said, “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with you!” (Lk.1:28 RSV). Only one without sin, without any barrier to grace, can be said to be full of grace. Mary’s sinless life was, therefore, a thing of wonder and joy to the angel. Gabriel declared to her the greatness which God had found in her. And, once her status was proclaimed, he was able to announce to her that she had found “favor” with God (Lk. 1:30). Because of her great holiness, she did not need any grace to heal her from sin, for she had no sin which needed healing, and yet she was to be given a favor, a boon, which separated her from all others: while still a virgin, she would conceive and give birth to a son, Jesus, the messiah and Son of God the Father (cf. Lk. 1:31-3). This special favor could be given to her because she had no sin, having nothing in her that stood in in the way of the full and total self-giving of herself to God, and therefore, nothing in her that could or would block God’s work in her. This boon, therefore, gave her a special role, indeed, a central role in salvation history, for it was the choice of God that she would become the mother of the messiah, Jesus, the God-Man.

More to Come.

[1] Orthodox theological styles use different means and explanations than is found in Roman Catholic theology, and as such, many Orthodox misread the Catholic response by engaging the wrong hermeneutic. And, likewise, many Roman Catholics, looking to the Orthodox, do the same thing, wanting identical theological methodologies when such is not necessary. Lack of charity allows this confusion to end in mutual hostility and division when it is not necessary. When those who are more charitable look beyond the beyond the words and theological logic used to explain the teaching and look to the teaching itself, and what is meant by it, this lack of any real difference between the two becomes readily apparent. And yet, as Vladimir Solovyov once noted, some in the Orthodox world lack so much charity that they end up denying basics of the faith if Rome promotes it, which is often why some Orthodox seem to slowly diverge from the general teaching and into erroneous propositions such as on the holiness of Mary (giving fuel for Protestant critiques of Catholic dogma):

This pseudo-Orthodox of our theological schools, which has nothing in common with the faith of the Universal Church or the piety of the Russian people, contains no positive element; it consists merely of arbitrary negations produced and maintained by controversial prejudice:

‘God the Son does not contribute in the divine order to the procession of the Holy Spirit.’

‘The Blessed Virgin was not immaculate from the first moment of her existence.’

‘Primacy of jurisdiction does not belong to the see of Rome and the Pope has not the dogmatic authority of a Pastor and Doctor of the Universal Church.’

Such as the principle negations which we shall have to examine in due course. For our present purpose it is enough to observe in the first place that these negations have received no sort of religious sanction, and do not rest on any ecclesiastical authority accepted by all the Orthodox as binding and infallible.

Vladimir Solovyov, Russia and the Universal Church. trans. Herbert Rees (London: Geoffrey Bless, 1948), 48.

[2] “And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen. 1:31 RSV).

[3] How she was conceived without sin will soon be explored, but for now, it is being taken for granted.

[4] While not important for our text here, it is worth mentioning that there is another potential effect of grace, its deifying nature, in which we find it lifts us up beyond our nature, and opens us up to be “partakers of the divine nature” (cf. 2 Ptr. 1:4).

[5] Theologically speaking, we can say that as long as Adam and Eve obeyed God’s will, they were sinless; they were in communion with God. That communion opened them up to grace, which, until they chose to act against God’s will, they received for their blessing. However, once they chose to act against God’s will, they closed themselves off from communion with God, and the grace which raised them up and made them holy was lost to them, so they were expelled from the paradise of God and entered into the world of sin. Sinlessness requires grace, for a will to holiness, even when someone is without sin, requires grace in order to execute such a will. And we find, in our saved state, we will not fall into sin, so that it is thanks to grace, that our heavenly existence will itself be sinless.

[6] We can also note another way God works to save us and that is by preserving our existence – giving us the grace which unites us to his being, so that our own becoming merges with being instead of decaying and becoming annihilated. Mary, therefore, realized in all her humility that without God giving a share of his being to her, she would perish, and so was able to call God her savior just by the fact he preserved her existence in creation.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing