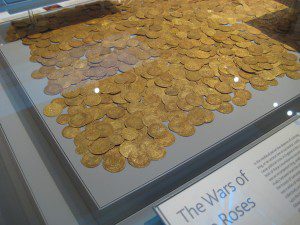

Photograph by BabelStone via Wikimedia Commons

Coming out of Israel, there is a tale of a poor pauper who worked hard, but still needed to beg for food in order to survive.[1] One night, worn out from the hard, pitiless labor, without getting enough money to buy food to eat, he cried out to God, begging for help.

Suddenly, a small bag appeared at his feet, and he heard a voice from heaven speak, saying, “When you open the pouch, you will find in it a single gold sovereign. Take it out and close the bag. When you open it again, you will find another gold sovereign in it. Every time you take out a sovereign, and close the bag, a new one will appear. When you have enough money, throw the bag into a river and keep what you have. Do not spend any of it until you throw the bag into the water, because if you do, the bag will turn into a fish and the gold coins into scales.”

The pauper thanked God for his generosity and went to sleep.

The next day, the pauper started to take gold coins out of the sack he had been given, one at a time, and placed them in another sack which he owned. Doing so throughout the day, he filled up the bag. That evening, as he was growing hungry he thought about throwing the bag into the river so that he could buy some food to eat.

“Wait,” he thought to himself. “Why should I throw this gift away all so quickly? I can beg for some food, just enough to make sure I have eaten, and tomorrow I can fill take more sovereigns out of the bag. Then I will have enough and be satisfied.”

And so he went out, begged on the streets until he got some food, barely enough to keep him satisfied, and then went home. The next day he continued taking out money from the bag, one gold coin at a time, until it was once again late in the day and he knew he needed once again to get some food and eat. Thinking, as he did the day before, that he was not satisfied with the gold he had collected, he went out to beg, getting barely enough food to survive another day.

This became the pauper’s daily activity. He would collect gold during the day which he could not and would not spend, and then he would beg at night, eating just enough to survive another day. He would constantly think it was time to throw the bag into the river, but each time he would stop himself and say, “Just one more day, and then I will be satisfied.”

He did this day after day, month after month, year after year. He never let friends or family visit him at home, giving them the excuse he was too ashamed for them to come over and see his place. And so he hid from all the gold which slowly accumulated in his home, as it filled the place with more gold sovereigns than he could ever use. But what use was such wealth for him? It was all worthless because he never was satisfied with what he had. He never gave up making more money. Until the day he died, he continued to follow the pattern of taking money out of the bag, finding a place to put it, and then begging at night. He became a very rich man, but because he began to covet money and sought to accumulate as much as he could, his avarice did him in, and he lived his life as a pauper, barely surviving despite the great wealth he had accumulated.

When he died, his friends and family were finally able to enter his house, and to their surprise, saw it filled with gold – indeed, there seemed to be no room for anything else but the gold. He who barely had enough food to eat died the wealthiest man in the world. Yet, as he was unable to take it with him, what good had it done him to die in such a state?

It is very easy to squander the blessings which God gives us. He desires the best for us, and out of love, will grant us much, but then we have a choice, to take the good given to us and use it for our good, and to share the bounty with others, or to try to take it, hide it, and keep it while never using it for what it is intended.[2] Money is meant to be used for the benefit of all, to be shared by all, and this means, it is not meant to be hoarded up and accumulated beyond measure. As with all goods it is meant to be used for the development of a just society, and this is impossible if the flow of such good is artificially halted. Those who receive more are expected to be good stewards and use it, not for selfish gain for themselves, but as a means to help those who are lacking – to make sure that the goods of the earth, meant for all, can be and will be shared by all. We must recognize that even the richest of us are but stewards of God’s bounty to humanity, not its possessors, and as such should seek to help in the universal distribution of God’s bounty to all, as Gaudium et spes explained:

God intended the earth with everything contained in it for the use of all human beings and peoples. Thus, under the leadership of justice and in the company of charity, created goods should be in abundance for all in like manner. Whatever the forms of property may be, as adapted to the legitimate institutions of peoples, according to diverse and changeable circumstances, attention must always be paid to this universal destination of earthly goods. In using them, therefore, man should regard the external things that he legitimately possesses not only as his own but also as common in the sense that they should be able to benefit not only him but also others.[3]

Sadly, as with many goods in the world, wealth is often abused, so that instead of being used for its proper end, to help in the just distribution of goods, many people love it for its own sake, seek after it, and collect it so that they can get way more than their just share of God’s bounty. The love of money, said to be the root of all evil, blinds us from the good intended with money and instead turns it into an idol which we seek after as our final good. Evil, after all, comes out of the inordinate application and use of the good – we do not seek evil for the sake of evil, rather, we will what we believe is to be good, though the good which we seek ends up being less than the good which we should seek. As we lose sight of the greater good, we are able to justify our sin because we will talk about it and explain it in relation to the good which we see contained in it.[4]

This is especially true with avarice. Greed has us entirely focused on the good we find in wealth. Usually, we begin our love for money by seeing what transitory goods we can gain from it: with so many goods which come out of money, how can our use of it be wrong? And so we see the good while ignoring the harm which is being done. This is why, as St. Anthony of Padua surmised, the rich fail to repent for their sins: “The thoughts of the rich of this world are: to keep what they have gained, and to sweat in gaining more; and therefore seldom or never is true contrition found in them. They despise it, being entirely set on transitory things.” [5]

And so, we see, how a lust for wealth, a desire for money, turns upon the one who holds such a passion, as it slowly makes them think that money is the greatest good. Money is transformed into an idol, and those blinded by its radiance end up losing sight of the true faith. “You see, therefore,” St. Maximus of Turin preached, “that whoever craves money loses the faith, whoever collects money squanders grace. For avarice is blindness and produces error in religion.”[6]

The blindness will come upon us so fast that we will not see it overtaking us before it is too late. Eventually, our heart will grow so attached to our idol, that we will do anything to appease it. That is, we begin to think that the only thing we should accomplish in life is the accumulation of money, and the more we do this, the better we become, even if it means sacrificing ourselves and our own livelihood for it. But what is to come of all such wealth in the end? It shall be taken from us from the wheel of fortune, either by grave disaster in our life which sees it vanish from our grasp, or, if that does not happen while we live, it certainly shall be lost to us when we die. And then, like the pauper in the folktale retold above, what good will it have done for us? Not a thing.

[1] Found in Folktales of Israel. ed. Dov Noy. trans. Gene Baharav (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1963), 44-5. I have adapted it for my own retelling of the tale.

[2] This is in part the message of the Parable of the Talents. cf. Matt. 25:14-30.

[3] Gaudium et spes. Vatican translation. ¶69.

[4] And since pleasure itself can be seen as such a good, many justify their sins purely on such a basis: if such actions are bad, why do they feel so good?

[5] St. Anthony of Padua, Sermons for Sundays and Festivals. Volume IV. trans. Paul Spilsbury (Padova: Edizioni Messaggero Padova, 2010), 156.

[6] Saint Maximus of Turin, The Sermons of St. Maximus of Turin. trans. Boniface Ramsey, O.P. (New York: Newman Press, 1989), 45.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing