In the Byzantine tradition, the Sundays of the Great Fast have set themes which provide spiritual and theological guidance. They play a central role in the liturgical catechism which teaches the faithful year after year the most important elements of the religious life.

![Icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy. Anonymous (National Icon Collection (18), British Museum) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/637/2017/03/Triumph_orthodoxy-236x300.jpg)

The Sunday of Orthodoxy teaches us both the place images have in authentic Christian worship, but also, more importantly, in the way God works in and with us through images which we can perceive in order to be directed toward him. Likewise, it teaches us that, before the incarnation, the defilement of sin impeded our access to the image of God within us, so that God forbid the construction of images which would have projected upon him our own sins; instead it is only through the purification of humanity and the restoration of human nature in Jesus, the Second Adam, that we have access to the divine through images. For it is through the revelation of God, and not the supposition of humanity, which allows God to be imagined. Furthermore, we no longer have to rely upon the image of God in humanity, a derivate image; rather, in the incarnation, the invisible God assumed human nature, personally providing to us a form which we can perceive with our senses which is authentically his, so that in through his body we can truly be said to see the invisible one, the son of the living God.

Moreover, even as see God in Jesus, so in Jesus God is able to see us in and through our form, in and through human eyes. In the person of Jesus Christ, the God-man sees us not just in and through his divine omniscience, but through his human senses. Just as we see and interact with Jesus through a visible form, through his image, so Jesus sees and interacts with us with a tangible, empirical form. Thus, we are told how Jesus saw Nathaniel, and through that encounter, he was able to tell Nathaniel that because of his guileless ways, he would likewise be able to see the kingdom of God with the Son of Man as its king:

Jesus saw Nathanael coming to him, and said of him, “Behold, an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile!” Nathanael said to him, “How do you know me?” Jesus answered him, “Before Philip called you, when you were under the fig tree, I saw you.” Nathanael answered him, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” Jesus answered him, “Because I said to you, I saw you under the fig tree, do you believe? You shall see greater things than these.” And he said to him, “Truly, truly, I say to you, you will see heaven opened, and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of man” (Jn. 1:48 – 51 RSV).

The gates of heaven, which were said to be closed to us because of our sin, were reopened when God became man. Now we can see God in and through Christ. The image of God in humanity, disfigured due to sin, is restored in Christ, and so in Christ, God is imagined and seen in perfect purity. God has revealed himself in his image, indeed in the perfection of that image in Jesus Christ. This is beautifully revealed in the hymns for the Sunday of Orthodoxy, in which the faithful sing:

No one could describe the Word of the Father; but when He took flesh from you, O Theotokos, He accepted to be described, and restored the fallen image to its former beauty. We confess and proclaim our salvation in word and images (Kontakion, Sunday of Orthodoxy).

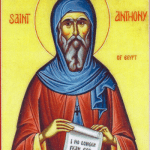

God, who is invisible and transcendent by nature, can and does reveal himself in his visible image implanted in ourselves. When sin defaced the image, humanity had lost sight of that image, and what it would try to produce in the image of God would therefore easily become an idol. The Mosaic Covenant represented the inability of fallen humanity to imagine God by forbidding the attempt to create any image. Only in the revelation of God in Jesus Christ does that problem subside, a revelation which includes the restoration of fallen Adam. This is why the triumph of Orthodoxy, which certainly celebrates the restoration of the images which iconoclasts had tried to destroy, parallels human history and exemplifies more than the restoration of holy icons but the restoration of the image of God within humanity itself. This, then, we can discern from what Pavel Evdokimov wrote as he explained the significance of the Sunday of Orthodoxy:

In 843, the Council of Constantinople once and for all reestablished icon veneration, and at the same time inaugurated the feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy. The church celebrates this feast on the first Sunday of Lent. But what it celebrates is not so much the orthodoxy of the icon, that goes without saying, but rather the image itself as the icon of Orthodoxy. This feast raised the icon to the level of a luminous light source in which all the dogmas are focused and find their harmonious expression. [1]

The icon represents the light which shines in the darkness, the revelation of God which reveals the light of truth which we can discern from the greater, mystical darkness of God; it is that which makes sure our faith in the transcendent God does not turn into agnostic nihilism. God transcends us and all that we can know of him. God cannot be seen by us because he is invisible by nature. God in his essence has no name which can properly be said to apply to him, for names are secondary constructs which are contingently established, but there is no contingency to God’s essence. But we can see God, we know him by many names which he reveals to us in and through his actions, and so we can know God even though he is clouded in the dark cloud of unknowing. He is known by his image, by the light which shines that is able to reveal where we are in the darkness of truth, but also in the light which comes to us and so shines in and through us as we unite with him through grace. The light makes sure we see and know God even if God transcends what we and know; it shows us our space in the darkness, revealing the truth of God which cannot be known.

The Sunday of Orthodoxy is the celebration that the truth has been revealed, that what we are unable to comprehend nonetheless manifests itself to us for us to know and love. It is, moreover, revealed to be truth which is not merely external to us, but a truth which comes to us and affects us from within. For the kingdom of God is within us and if we are to see God, we must look within and see the light shining in us, in the image of God in us. When we do, we will see Christ, the living God, who sees us, like Nathaniel, dwelling under the fig tree. For we are all heirs of Moses, who abandoned all earthly glory for the sake of the Christ who was to come:

By faith Moses, when he was grown up, refused to be called the son of Pharaoh’s daughter, choosing rather to share ill-treatment with the people of God than to enjoy the fleeting pleasures of sin. He considered abuse suffered for the Christ greater wealth than the treasures of Egypt, for he looked to the reward (Heb. 11:24 – 26 RSV).

The law of Moses is one with the law of Christ. To be saved in Christ is to be put under the fig tree, not because we are to be Israel in the flesh, Jewish by blood, but because we are called to the heavenly Israel which the earthly Israel was a mere representation. Moses, the Temple, the people of the earthly Israel must be respected because salvation is of the Jews, but we must see in and through them the slow, developing revelation of God which is fulfilled in Jesus Christ, and once fulfilled by Christ, able to be seen and witnessed in all of us in our own inner hearts.

[1] Paul Evdokimov, The Art of the Icon: A Theology of Beauty. Trans. Fr. Steven Bigham (Redondo Beach, CA: Oakwood Publications, 1995), 163.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing