Soon after soon after being tortured, having his tongue and right hand cut off, and then being sent into exile, the elderly St. Maximos died. Born around 580, he would fall asleep in the Lord on August 13, 662.He was one of the great intellects and spiritual masters of the Christian East, recognized as such during his life, which is why when he took a stand on an important and divisive theological issue, what he said would be noticed by all in positions of authority. In Byzantium, the emperor, Constans II, was interested in consolidating his power, and that included finding a way to pacify non-Chalcedonians with decrees that silenced Christological discussions which caused conflict. One such discussion which he forbade was on the number of wills which existed in Christ; the previous Emperor had actually affirmed one will and energy in Christ, with the Patriarch of Constantinople supporting him. Maximus had debated that position, and had, for a time, even got the Monothelite Patriarch Pyrrhus to proclaim with him that there were two wills in Christ, making that declaration known – only to recant when Constans was in office.

Soon after soon after being tortured, having his tongue and right hand cut off, and then being sent into exile, the elderly St. Maximos died. Born around 580, he would fall asleep in the Lord on August 13, 662.He was one of the great intellects and spiritual masters of the Christian East, recognized as such during his life, which is why when he took a stand on an important and divisive theological issue, what he said would be noticed by all in positions of authority. In Byzantium, the emperor, Constans II, was interested in consolidating his power, and that included finding a way to pacify non-Chalcedonians with decrees that silenced Christological discussions which caused conflict. One such discussion which he forbade was on the number of wills which existed in Christ; the previous Emperor had actually affirmed one will and energy in Christ, with the Patriarch of Constantinople supporting him. Maximus had debated that position, and had, for a time, even got the Monothelite Patriarch Pyrrhus to proclaim with him that there were two wills in Christ, making that declaration known – only to recant when Constans was in office.

St. Maximos was concerned about what truth was revealed in the incarnation, and not what empires wanted to promote for the sake of political intrigue. He could and would follow an emperor who submitted to orthodoxy and orthopraxis, but when politics was used to silence the preaching of the gospel. Maximos, who at one time had been Protoasecretis of the Emperor Heraclius before becoming a monk and religious scholar, thought that it was the duty of believers to speak up, even if and when those around them would not do so.

The theological question at the time was related to the person of Jesus Christ, and how Christians were to understand the relationship of his two natures, divine and human, to the way he acted as a person. For some, it seemed simple: he was one person, so he should be said to have one will, and he acted according to that will. The problem Maximos saw with this is that it either diluted the divinity, changed the humanity of Christ, or both at once. The incarnation would result in a real change for the divinity and an alteration of what it means to be human, instead of the recognition that the divinity is unchanging and humanity was not absorbed or changed in nature as a result of the incarnation. For Maximos, to understand who Jesus is, to understand what it meant for him to be God and man, he had to be seen and understood as acting in accordance to both of his natures. As God, Jesus acted as God, and as man, he acted according to his humanity. The two natures could not be confused, so their activity could not and should not be confused. Yet there had to be some sort of unity between the two, as they came from one and the same person, so they were to be understood as to be cooperating with each other, acting together and not in opposition to each other, even if they acted and worked differently.

To understand what this meant in Jesus, Maximos reflected upon what Jesus did in accordance to his humanity, showing how and why such actions had to be seen as willed by a human will, and not by some divine will. When he did something normal to human activity, such as eating and drinking, he clearly was acting as a human and willed as a human, but since the divine does not eat or drink, he could not be said to will such according to his divinity. Likewise, as he was God, he continued to act as God, for God is simple and eternal and unchanging; his divine will consistently acted as it always did, in and through his simple eternity, in a way which his humanity could not act: he was the creator and sustainer of the world. His divine action showed he willed as God in a way which his humanity could not be said capable of doing. In this way, Maximos was able to that while Jesus had two wills and two works or fruits of his activity, it was necessary to see them as separate lest one of the other gets lost as a result of the incarnation and humanity and the rest of creation would suffer from that loss.

We can read examples of this in Maximos’ writings. In his debate with the Patriarch, Pyrrhus, he described activities of Christ which could not be attributed to Jesus’ divinity:

In the Holy Gospels it is said of the Lord that “one day the following, Jesus would go forth into Galilee.” So, as it is apparent that He willed to come there, inasmuch as He was not already there, then it is obvious that He was “not there” according to His humanity, for His Godhead was absent from no place. Consequently, He willed to come into that place as man, and not as God. And therefore He possessed the will which is proper to man. And elsewhere again, “I will that where I am, these may be also.” If Christ, as God, be beyond place, for as God He is not in any place, and if it be impossible that the created nature should be beyond place, then He willeth according to that [nature] which He is as man, in order that where He is “these may be also.” Therefore, He possesseth the will [which is] proper to man.[1]

Yet, the key remained, Jesus was God, the second person of the Divine Trinity. He came into the world, assuming human nature and all that was in it to himself, while not changing his divinity in the process. How could he become human If he did not will as human? It was not some vain imagination or deception which made it appear he became man: he literally became man, acting and living as a man, while remaining God. Truly there is a sense of paradox going on here, indeed, Maximos thought it was perhaps the greatest paradox we could contemplate as Christians:

And what greater paradox could there be than that whereas He is God by nature and deemed it fitting to become man by nature. He did not alter the natural definitions of either one of the natures by the other, but being wholly God He became and remained wholly man? For being God did not hinder Him from becoming man, nor did becoming man diminish His being God, and thus He remained wholly one and the same in both, truly existing naturally in both, being neither divided by the unadulterated integrity of the essential differences of the two natures, nor confused by the fact that the two natures came to exist in an absolutely single and unique hypostasis, and so He neither changed nature nor underwent a transformation into something He was not. Neither did He fulfill the plan of salvation in an imaginary form or simulated appearance of the flesh (as if He had simply appropriated the accidents of a substrate without the actual substrate itself), but to the contrary He made human nature His very own –literally, really and truly – uniting it to Himself according to the hypostasis without change, alteration, diminishment, or division, and maintaining it unaltered in accordance with its essential principle and definition. [2]

For us, with minds unable to comprehend God, it is clear we will not be able to understand in full the way God acts and so how he could become man. We can understand the concept, we can see the truth of it, but in the end, we will find ourselves coming up with conclusions about the Godman which appear to be self-contradictory and yet end up being necessary. The limits of the human mind, and its mode of engaging the truth, will always find the truth beyond it and leading to such apparent contradictions when any transcendent truth is explored. God is beyond human logic, but that should not be a surprise, for our logic breaks it down when put next to absolute reality. Revelation gives us truth which lies beyond our reason – though we can and should use reason to understand revelation and demonstrate why we believe it. Reason knows its own undoing, its own weakness, its own need beyond itself, for all reason engages what is given to it, and employs its own carefully constructed tools for the discernment of truth. Yet those tools are crude in comparison to the transcendent truth and so will need to be abandoned if we want to come to the fullness of truth itself. The further we are from the truth, the more useful such tools will be, helping us edge closer to what lies beyond us, but the closer we are, the more their weaknesses will be seen as they produce paradoxes which we cannot and must not try to overcome. And so, in Jesus, we have God and man, one person who is both the transcendent, incomprehensible reality itself and yet also human, constrained by the limitations of human existence. He does not change his divinity, nor does he alter humanity – but yet he makes a way so that the two can come together. Thanks to him, and in and through him, humanity now can become partakers of the divine nature.

These paradoxes go further than questions concerning the hypostatic union and the ways the God-man wills both as God and as a man. By assuming humanity unto himself, he assumed the weaknesses of all of us, so that what is done to the least of us is said to be done to him. In this way, it is possible to be said that these things are also done to God. Thus, the good of evil which is done to the poor, the weak, the afflicted, is said to be done to God. Likewise, in the incarnation, God has become not just human but he has taken on the poverty of humanity, emptying himself so much that he takes on the poor in humanity in himself and makes himself one with the poor. When we encounter some poor man or woman, full of suffering or heartache, we come face to face with him as well. This is the reality of the incarnation and what it meant for God to assume human nature, and if we want to understand truly the incarnation, we must come to term with the relationship between God and the poor. This is why Maximos was able to say that all the suffering of humanity, all the hardship and abuse the poor and abused face, is taken unto him and why we are to say, the poor we have with us until the end of time, is really him:

For if the Word has shown that the one who is in need of having good done to him is God – for as long, he tells us, as you did it for one of these least ones, you did it for me – on God’s very word, then, he will much more show that the who can do good and who does it is truly God by grace and participation because he has taken on in happy imitation the energy and characteristic of his own doing good. And if the poor man is God, it is because of God’s condescension in becoming poor for us and in taking upon himself by his own suffering the sufferings of each one and “until the end of time,” always suffering mystically out of goodness in proportion to each one’s suffering. [3]

Jesus the eschaton become immanent, for in him the suffering of all is found; in his person, in his historical place in time, he has taken up all of time and revealed its end and leads it to transcendence. It is finished – it is ended – the end truly has come in Jesus. Now he is the poor with us to the end of time, for the end of time is subsumed in him; he brings together the whole of creation as one. He is the beginning and the end and all things find themselves in him as one, so that through him, they can be given the deifying grace which perfects their being, overcoming the non-being which sin sought to produce in creation. He took on the poverty which sin established so the plentitude of divinity can be all in all.

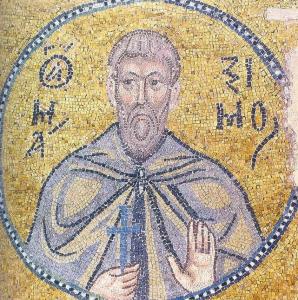

[Image of St. Maximus via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] St. Maximus the Confessor, The Disputation with Pyrrhus. Trans. Joseph P. Farrell (South Canaan, PA: St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 1990), 42-3 [130].

[2] St. Maximos the Confessor, On the Difficulties in the Fathers: The Ambigua. Volume II. ed. and trans. Nicholas Constas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 131-3 [Amb. 42.6]

[3] St. Maximus the Confessor, “The Church’s Mystagogy” in Maximus the Confessor: Selected Writings. trans. George C. Berthold (New York: Paulist Press, 1985), 212.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook