And so that you might see the disposition that is associated with true prayer, I shall offer you not my own but blessed Antony’s opinion. We know that he sometimes prayed at such length that frequently, when he was in an ecstasy of mind while praying and the rising of the sun was beginning to shine forth, we would hear him declaring in his fervor of spirit: ‘Why are you hindering me, O sun, you who are rising now in order to keep me from the brilliance of the true light?’ From him also come these heavenly and more than human words on the end of prayer: ‘That is not a perfect prayer,’ he said, ‘wherein the monk understands himself or what he is praying.’ [1]

St. John Cassian (c. 360 – 435), journeyed into the Egyptian desert to interview and learn from the spiritual masters of his day. Through his work, he was able to learn some of the oral traditions which were passed down in the desert, preserving them in his work so they would not be lost. It is in his conversations with Abba Isaac we have this remembrance of St. Anthony in which we learn what his disciples remembered him being like when he was lost in prayer.

Anthony, like other mystics, knew there were many ways we can engage prayer. All of them have a sense of comfort being given to the people of God, but the kind of comfort depended upon the kind of prayer being done. Petitionary prayer comforts us because we hand over our desires to God, allowing us to take the burden off of ourselves as we trust in God’s faithful response to our prayer, working for what is best, whether or not it is what we desire. Nonetheless, there are other forms of prayer, with the greatest, “perfect prayer,” being a kind of union between us and God. This can only take place if we transcend ourselves, cutting off all thought of the self and all that is associated with the self, so that we forget the self and let the glory of God reveal itself to us without anything, including ourselves, getting in the way. It is prayer; we will be able to speak to God, not with words, but in our silence, in our union with him, and God will respond in that silence with his transcendent silence, revealing to us the truth of himself to us. Words will be lost. Thoughts will be lost. Our intellect will be lost. The self will be lost. There we will find ourselves in that transcendent meditative experience which develops once the self is put to rest and the mind is silenced, where God is all in all and we live and thrive outside of ourselves, truly as persons in loving union with God.

It can be difficult, even for great spiritual masters, to attain such transcendent silence. We have to struggle against ourselves and the things which would call out to us and have our attention. That means, there can be distractions which limit our meditative prayer. Certainly, through the grace of God, some might not have distractions at one time or another, or even have overcome them through their spiritual practice, but for most of us, even for most great mystics, distractions will come. We must recognize them and fight against them the best we can without giving in to them or becoming upset about them. We should shrug them off when we notice them, and return to our meditation. This is easier said and done. This remembrance of St. Anthony showed that he could become distracted by the things of the world, and he would confront them in his own way, trying to overcome them so that he could return to his prayer.

It is important to realize that when we have overcome ourselves we can still become distracted from the world itself. When God comes to us in a still small voice, when God reveals himself in silence, we must be properly attuned to God with nothing getting in the way if we want to continue in such perfect harmonious union with him. This struggle is for our own good. It is purgative. It helps purify our love and desire for God, preparing us to receive God in a better way once we break through the barrier of the world. Secondly, we also must realize, as much as we want that union with God, we do not control God and how he acts or reacts with us. We cannot expect to have the same experience each time we try to enter into such contemplative prayer. We can learn and engage many spiritual disciplines which put us in a position to be ready to encounter God, but we cannot assume God is to be controlled by such discipline and he will come to us as we want when we want. This is why we must not confuse the discipline and practice which we learn to help silence ourselves as a kind of technique which puts God in our control and makes him reveal himself once we have died to ourselves. Such silence puts us in the proper disposition to be a hearer of the word of God, but then we must wait for God. While waiting, it can be extremely difficult to sustain the silence; with our awareness ready for revelation, the world reveals itself to us, and so external distractions can get in the way; when God comes, we might find those distractions screaming over the silence of God, making it difficult to receive all that God could give to us if we were truly attentive on him alone.

Different people, different spiritual masters, will find their own way to pray and engage God in silence. Some will be able to do so easily while at work, contemplating on God while their body engages its labor by rote. Others will find that too distracting; though they will engage work with a meditative spirit, they will need time alone, time in silence and inaction, to truly lose themselves in God. From what Cassian recorded, St. Anthony found his best time for such prayer was during the night, where he could find himself in solitude, with the world itself engaging, as it were, a kind of silence with him. In the silent darkness, he found it is easier to grasp the loss of the self, to slowly feel oneself dissolve in that darkness; in it, he found no light to bring forth the created order with all its glory to distract him. In the depths of the night, he could embrace the silence of the world, embrace it, let it take him over, and then pray, to pray long without thought of time or place, to pray without thought of who or what he was. When the sun came up, the darkness which easily hides the world from him was slowly pushed aside, making it difficult to remain in an undistracted state. In this fashion, Anthony complained about the light of the sun covering up the light of God which he saw in his spiritual ecstasy; this is not to say the sun is greater than the light of God, but rather, because it is more immediate to us and our senses, it was able to get between him and God and bring him out of the silence of the night and back into the noise of day.

The purification of the dark night of the soul is, in a way, best experienced in the dark night of the world; the two go together naturally, indeed, earthly night in itself can help serve as the natural foundation for the mystical night where all the senses over overcome and the person experiences their nothingness beside God. Here, truly, by not knowing one self, we truly get to know the inherent emptiness of that self, and so to realize the proper relationship between us and God. There will be no question of our inherent nothingness even as there will be no question of God’s transcendent reality. We will understand God and his dispensations better, of how the nothingness from which we flow allows us to be filled by the glory of God so long as we keep to that emptiness and do not create and objectify a false sense of self. Thus, we read from Nikitas Stithatos in the Philokalia:

When you know yourself you cease from all outward tasks undertaken with a view of serving God and enter into the very sanctuary of God, into the noetic liturgy of the Spirit, the divine haven of dispassion and humility. [2]

Perfect prayer brings us comfort because it brings is in union with God, who is the source of every good. But it is long and difficult to get to that state. We must slowly learn to cast off all our thoughts and desires, including and especially, our sense of self so we can regain it all in God. The process of prayer begins with our voice speaking our wishes and desires, giving them over to God, learning to trust him in how he handles our request. This is prayer and a way for us to engage God, and a way for God to work with us and instill his grace in the world. We can think of such prayer as the means by which we give out our hopes and dreams and hand them over to God so we can put aside all earthly cares. We must all learn to try, even if for a few brief moments, to cast it all away, so we can stop thinking of them and slowly find ourselves in the perfect silence in which God is to be found. We might not be able to do this for long, but that is alright; we who live in the world still are called to live in the world, to take the grace found in that brief rest and return to the world with all its noise, refreshed and capable of making it through another day.

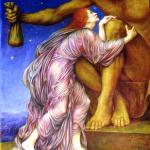

[Image=Evening Prayer by Francesco Peluso [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1]Abba Isaac in St. John Cassian, The Conferences. Trans. Boniface Ramsey, OP (New York: Newman Press, 1997), 349.

[2] Nikitas Stithatos, “On The Inner Nature of Things” The Philokalia. The Complete Text. Volume IV. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al (London: Faber and Faber, 1995), 117 [¶ 38].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook