Catholicism, despite its dogmas, allows for a great variety of theological opinions. This is important because it means Catholicism is not about reducing the faith to one or another particular school of theological opinion. It does not force people to stand behind what many believe to be true so long as what is believed does not contradict the core dogmas of the faith. Sometimes, a school of thought becomes so well-known, so well-employed, that many confuse its particular positions as necessary for being Catholic. Both St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas have had their theology used in this way, but, it is clear to those who study their writings and not merely the presentation which has developed from their later disciples, neither of them would have wanted to reduce the creative engagement of Catholicism to their own questionable speculations.

Catholicism, despite its dogmas, allows for a great variety of theological opinions. This is important because it means Catholicism is not about reducing the faith to one or another particular school of theological opinion. It does not force people to stand behind what many believe to be true so long as what is believed does not contradict the core dogmas of the faith. Sometimes, a school of thought becomes so well-known, so well-employed, that many confuse its particular positions as necessary for being Catholic. Both St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas have had their theology used in this way, but, it is clear to those who study their writings and not merely the presentation which has developed from their later disciples, neither of them would have wanted to reduce the creative engagement of Catholicism to their own questionable speculations.

It is important for Catholics to realize that just because a particular opinion is well known, and well used by many other Catholics, it does not mean that the opinion holds doctrinal weight. Indeed, throughout history, many popular pious opinions get overturned, causing some confusion because they believed the opinion to hold some authority which it did not. So long as opinions do not conflict with what is authoritatively taught, they can be believed, but like approved apparitions, that does not mean the faithful have to agree with them. Merely contesting a popular opinion does not make someone a heretic. Merely rejecting the theological opinions of great saints, even of Doctors of the Church, does not make someone a heretic. Showing someone the opinion of an important, indeed influential theologian, does not validate the teaching as true (nor, of course, does it mean those who deny such opinions are right, either). Catholicism allows people to be wrong with so many elements of their theological opinion so long as the error does not pit people against the greater truths which must be believed.

Nonetheless, because of the confusion which is often had by those who have not studied theology, many will automatically assume more authority for popular beliefs and practices than are necessary. If, later, some of those opinions become questioned or denied by ecclesial authorities, those who hold to them believing them to be doctrinal will become confused. If the church has not denied the possibility of such opinion, they do not have to change if they do not want to, but on the other hand, if the church in making a decision gives an affirmative denial of what was once popularly believed, the faithful will need to take heed and follow the church (seeking, of course, to understand why the objection was made). For those who are faithful, this is enough; they might be confused, they might recognize their own confusion and accept it, but others will think they know better, and will demand the church follows what it has authoritatively denied. Depending upon the level of magisterial authority employed, and the level of reaction against the Magisterium, this is where someone can fall into heresy, with a willful denial of the positive authority of the church. To be sure, questioning the magisterial teaching alone is not enough for this heresy; it has to be a rebellious rejection which almost calls the church itself to be in heresy to rise to the level of serious theological error. There can be a great amount of grey room between the two, especially when the magisterial teaching is not clear (studying the history of Christology should make this plain; many who are not authentic heretics denied what the church proclaimed due to misunderstanding, which when it was made clear, enabled reunion between separated parties, such as John of Antioch and St. Cyril of Alexandria).

When, then, theologians and the Magisterium come to declare a particular position is not doctrinal, some will then contend against the church itself, many who were led to believe that particular teaching was doctrinal will think the church is rejecting its tradition and causing scandal, while others, who were not particularly attached to the notion in such teachings will feel not only relief, but vindicated as the truth comes out.

A great example of this is the idea of limbo. It was never an official teaching of the church, but a great number of people, including ecclesiastical authorities, believed in it causing many to believe it stood as one of many parts of the overall Catholic faith. While Catholics are free to believe in it, if they so wish, reexamination of patristic theology has helped many to look beyond the context in which limbo made the most sense; such a context is a particular school of theological thought which Catholics can hold to, but need not, and with the greater awareness of the variety of theological thought found within the church, many of the concerns which were raised which led to the consideration of limbo (what happens to those who are not baptized for no fault of their own?) can be and are answered in a variety of fashions (such as suggesting that God is not confined to rituals, so that he can give out the grace of baptism in other ways beyond the normative ritual). The notion of a pure nature, existing independent of grace, is also necessary for limbo to make some theological sense, but that notion itself is troublesome because it ignores the relationship between existence and grace and how all existence is itself radiated by grace.

Sometimes, an advance in philosophy or science requires is to reconsider past opinions. When what was assumed to be true of the natural or metaphysical world is shown to be false, theological opinions which were based upon previous assumptions have to be re-examined if not changed. Often, in theology, all that we can do is take our limited understanding of the world, add to it the doctrinal teachings which we know to be true, and derive from the two speculative opinions which best put them together. We must not assume too much about our knowledge; we must allow, in humility, that we can be wrong. Moreover, we must accept that sometimes we will not know the answers to the questions which burden our soul. We must accept that all we can do is make educated guesses, and realizing this, we can realize this was also true with those who came before us as well.

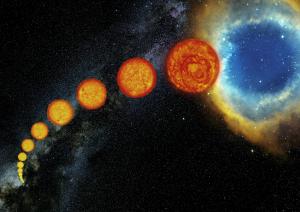

Biological sciences have developed a great deal in the last century, and notions the sciences often had of animals, of what they are like, of their potentiality, of their relationship with humanity, has changed. Through evolution, we know we are related to them; through evolution, we know they are far more similar to us than we once thought. Biologists have learned that, contrary to what was assumed, animals often have sense of reason, passions and feelings of their own. Theological reflection which was based upon the notions that animals had no sense of reasoning themselves, therefore, must be abandoned, and yet much of what Christians assume about animals and their eschatological fate came out of such assumptions. Perhaps no better example of this is the argument used by many to suggest why only humans, and not the rest of the animal world, has potential for eternal life: it is said that only rational animals could benefit from that grace. Nonetheless if animals can be shown to have some level of reasoning ability, then the assumption that they cannot enter into eternal life must also be questioned. Indeed, there are many theological grounds by which their place in eternity make sense, especially the scriptural fact that Christ’s work in the world was not for humanity alone, but for the whole cosmos. St. Maximus the Confessor, following the cosmic sense of Christ’s work, posited the notion that Christ’s actions integrate the whole of creation into his deifying grace, overcoming those artificial divisions which exist in the world as a result of sin. He saw this not only in division between male and female in humanity, but of humanity with the rest of animal creation. Likewise, the distinction which was believed to exist between humanity and the rest of the living beings of the world was often based upon the false assumption of pure nature, thinking it is pure and unchanging. Evolution has helped counter that, but theologically, this should not be surprising: God’s work for the deification of creation seeks to raise it up beyond its initial status. It should not be difficult to believe that God looks to and takes care of the whole world with his grace; animals are shown his love and grace; their potential might differ, but that is itself a reason for and why God would also love them and raise them up as well: the beauty of creation, the greatness of God’s glory, is manifested in the diversity of being, and animals, being preserved and sharing in eternity, would then be a proof of the goodness of all his creation.

Cosmological sciences have also developed from the ancient world to the modern age, giving way, once again, to reasons why our theological opinions need to be modified. The earth is not the only place in the universe; nor is it to be seen as the absolute center of the universe. Nicholas of Cusa, centuries ago, understood the ramification of this, and so accepted with ease the possibility of life, intelligent life, as existing elsewhere in the universe (realizing, moreover, every point in the universe could relatively be seen as its center). We must not assume our lack of experience with them, nor the silence of their existence in the revelation, indicates their non-existence; science, with its cosmological and evolutionary understanding, would suggest, even if we do not meet such species, they exist and are a part of God’s great work. Who they are, what they are like, how God works in and with them, we can only guess unless we meet with them. But the key is to realize that the plurality of worlds with a wide range of intelligent species does not have to be seen as contrary to the Christian faith, and in light of the size of the universe and the way God works in creating life as a way of expressing his glory to creation, we can see that the likelihood of their existence is best accepted. We can theorize what they are like; we can question whether or not they are fallen or unfallen beings (I assume they are fallen); but they do not challenge us because we can look to the cosmological significance of Jesus as giving us reason, once again, to accept that Jesus would have his way to incorporate them into himself, bringing them to the eschaton with him if they do exist.

The biological and cosmological examples above only serve as instances of how modern science has transformed our understanding of the universe and as such, allows for, if not expects, revised theological models to be made to deal with them. It is how Christian theology has always worked. When Christians did not know of the Americas, they had a rather limited understanding of their place in the world; once they became aware of the Americas, they had to take stock of the new knowledge and transform their awareness, allowing for a growth in natural theology and appreciation of how God could and did work with those who seemed to be outside of the normative community of the People of God. It is not something to fear, but rather, as with all exploration of the truth, something to be accepted and marvel at. The world is beyond us and our constructs; we must always remember our theological constructs serve as pointers to the truth; they help point the way, but as we develop, as our understanding of God develops, we must be able to look to the spirit of theology in the past, overturning the letter it was found in, so we can embrace and engage the wider, surprising truth God has given us today. If we do not, we risk finding ourselves off not only from the truth, but from God, the source of truth, who seeks to enlighten us with his grace. For if we resist the simpler truths which we become aware, we risk closing ourselves off from the source of such truth, which is God, closing in on our own understanding instead of letting God marvel us with the fullness of grace found in his truth.

[Image=Life of Sun Like Stars by ESO/S. Steinhöfel (ESO) [CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook