As we seek after the truth, we normally try to explain it to ourselves in forms which we can comprehend, such as when we set out and create definitions which we use to establish the parameters of the truth. While the truth can be represented in this fashion, we must keep in mind what we establish is not the truth as it is in its absolute form, but a conventional expression of the truth which approximates the truth according to our own ability to understand it. It can be said to be the truth insofar as it participates and points to the truth, but when we disconnect it from the absolute and turn it into the absolute truth, we no longer hold onto the truth and establish falsehood instead.

As we seek after the truth, we normally try to explain it to ourselves in forms which we can comprehend, such as when we set out and create definitions which we use to establish the parameters of the truth. While the truth can be represented in this fashion, we must keep in mind what we establish is not the truth as it is in its absolute form, but a conventional expression of the truth which approximates the truth according to our own ability to understand it. It can be said to be the truth insofar as it participates and points to the truth, but when we disconnect it from the absolute and turn it into the absolute truth, we no longer hold onto the truth and establish falsehood instead.

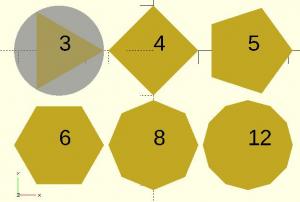

Growing in wisdom and understanding, we will find our conventions, our representation of the truth, changing, becoming more refined; we will be making better and better approximations of the truth, similar to the way Nicholas of Cusa suggested in his works, the more sides a polygon has, the better it will approximate and represent a circle. Thus, we will take our definitions and begin to deny them, abstracting from them what we discern is less than the truth itself; then, we can and will celebrate the greater truth which has been revealed once we have abstracted away the dead letter of our conventions, as Dionysius explained:

And, it is necessary, as I think, to celebrate the abstractions in an opposite way to the definitions. For, we used to place these latter by beginning from the foremost and descending through the middle to the lowest, but, in this case, by making the ascents from the lowest to the highest, we abstract everything, in order that, without veil, we may know that Agnosia, which is enshrouded under all the known, in all things that be, and may see that superessential gloom, which is hidden by all the light in existing things.

When we establish definitions to express the truth, we must understand what we are doing. We are using words to define what is beyond words. We are using earthly forms and symbols to point to the transcendental truth. There is value in doing this; it is an important part of the process by which we ascertain the truth. Indeed, we can see God has affirmed this aspect of the truth, the immanence of the transcendental truth, through the incarnation. God emptied himself of his glory, putting on an earthly form, by which we can come to know him. When we want to express the truth, we must understand we are putting it in a form which can reveal the reality of the truth without however changing its absolute transcendental nature. But to do this effectively, we must search for the truth of God in all things; we must lower ourselves, following the descent of the Word in the incarnation, into all that is, finding in all things the immanence of God, so that through all things, we discern not only that God is, but God is great, full of love and compassion, embracing all things in himself.

This is how most of us start our search for understanding: we bring the truth of God down to a level which we can comprehend. Kataphatic theology, filled as it is with symbols, definitions and declarations, is useful as it establishes a foundation for our faith, giving us reasons which we can use to help us understand some of the logic behind what we believe. But we must always keep in mind the limitations of such a theological enterprise; our mind, its thoughts, the words and definitions which we use for those words will not contain the fullness of God in them. They serve us, but we must not serve them; they help us pass down the faith throughout the ages, but what they pass down is a mere reflection of the absolute truth itself.

We must not treat these foundations as representing more than they do; they point to the truth, and turn us away from falsehoods which are not the truth. They serve to cut away gross falsehoods, beginning the apophatic process: to say God is one is another way to say God is not two. When we understand the definitions and distinctions which the Christian faith proposes, we can then see how they serve to negate what is not and use that to help us begin our journey towards the fullness of truth which is found in the abstracting of all that is not truth away from it. Dionysius, therefore, must be seen as writing to those who are already firm in their faith and are ready to seek out the truth of God in God himself. He is not telling us to deny the truths of the Christian faith, but to realize how they are expressed in human conventions are less than what they are in God himself. They approximate the truth in a form which we can have some understanding, but then, in seeing the truth in them, we should come to love God and seek him directly.

We must begin with the basic foundations of the faith and begin to ascend beyond them, cutting away from the symbols where they differ from God, purifying them so that God can be revealed more and more with less and less veiling him from ourselves. Thus, as Dionysius said, we abstract everything, in order that, without veil, we may know that Agnosia, which is enshrouded under all the known; what is known about God is all in a form which is not God. As we abstract from our knowledge what is less than God, we begin to see that all that we know will be abstracted away until we reveal God in our ignorance. It is to be a process of abstractions, not an instantaneous leap: we abstract a little at a time to let more of the truth of God be revealed to us. If we try to jump into silence, we will confuse the mystical Agnosia with simple ignorance and end up denying God instead of denying our attempts to comprehend God. Our abstractions must be an ascent to transcendence instead of a descent into nihilism; we must grow in truth as we accept our unknowing, but the unknowing has to come from a foundation of truth: where the truth is veiled in conventional forms, we remove from ourselves those veils, not the truth itself. We abstract, thus, to accept our ignorance, but an ignorance formed on truth not apart from it; we abstract, having come to the truth, but knowing we do not comprehend it; we abstract so that we may know that Agnosia, which is enshrouded under all the known.

God is Agnosia, that is, unknown, found in all things and known through them, but what is known is not God himself but his vestiges. He is found in all things, hidden in all things even as he transcends them. His immanence is one with his transcendence; in all things he lies hidden, a light which shines in the darkness and directs and illumines all things which is itself so bright, it is a superessential gloom. The more we seek to comprehend God, the more we constrict God and hide him in the things which he is not, but the more we let go and abstract away all that is not God, the more the veil is removed, until at last, we kick away the veil of knowing so that we can have the Unknowable God himself. Thus, Robert Grosseteste explained:

For whatsoever is known in any existing thing whatsoever is a veil of that great transcendence, and that we may see that transcendent darkness, that is, the same inaccessibility of light, hidden, by its very own inaccessibility, of course, from all that light which is in existence, that is, from every knowing power that is created; for no such power can attain to him.[1]

We seek to know God, but to know him, we have to accept his incomprehensibility. He is unknowable and yet knowable, for he reveals himself to us. What we assert comes from him, but yet it is not him. We must deny what he is not from what we have affirmed if we want to rise up to him. We shall then know he is but not what he is. We shall know and not know, we shall be lifted up and yet even then he will be unknowable because of his transcendence; he is the bright light which reveals all truth in a brightness that overcomes our perception, and yet having seen that light, we attain him and know him to be and love him in the beauty which he is. We cannot comprehend him; we cannot know him as he is, but yet we know him and love him. Indeed, in that love we find ourselves joined to him, so that we come to know him through and all things through himself. Thus, we must accept our unknowing so we can come to the one who is unknowable, but we must accept it not because there is nothing to know, but because he alone is the one worth knowing.

[IMAGE=By LABoyd2 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons]

[1][1] Robert Grosseteste, “De Mystica Theologia” in Mystical Theology: The Glosses of Thomas Gallus and the Commentary of Robert Grosseteste on De Mystica Theologia. Trans. and ed. By James McEvoy (Parish: Peeters, 2003), 93.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook