Technologically is radically changing the modern world. Machines can and will replace all kinds of human labor. The job market will shrink as the need for human labor will vanish. While it is unlikely that all jobs will be eliminated, the number which will be overtaken by technology will require humanity to reconsider its relationship between work and wealth. If and when the need for human labor is far less than the number of people alive, either excuses will be made for a massive reduction in the human population through all kinds of unseemly, immoral means, or, wealth will have to be distributed in a way which is unrelated to labor.

Technologically is radically changing the modern world. Machines can and will replace all kinds of human labor. The job market will shrink as the need for human labor will vanish. While it is unlikely that all jobs will be eliminated, the number which will be overtaken by technology will require humanity to reconsider its relationship between work and wealth. If and when the need for human labor is far less than the number of people alive, either excuses will be made for a massive reduction in the human population through all kinds of unseemly, immoral means, or, wealth will have to be distributed in a way which is unrelated to labor.

As it is, this is already a problem, which is how and why the value of labor is diminishing. More and more people find themselves no longer needed in the workforce. They either work less, receive less pay for their labor, or worse, cannot find a new job as they are pressed into poverty.

This will only get worse, not better, so long as we remain with outdated models of wealth distribution. The libertarian and so-called conservative responses merely suggest workers need to find better jobs, acting like it is easy to do so and if someone does not, they must be lazy and worthless. The reality is far different. While there might be a few jobs available, the number of jobs needed for everyone to find success is not there. The ability of a few to get such jobs should not be used to hide the real fact which lies before us: real good paying jobs are becoming less and less available.

While it is likely that in the foreseeable future the economic might of those who possess most of the wealth will continue to control the economic narrative, in the end, the system is going to break, and a new, more just system based upon the new economic reality will have to be established. Eventually, work will not be entirely connected to one’s livelihood; some form of guaranteed income will be established so that no one will have to live day by day fearing a loss of basic necessities such as food, shelter and clothing. The sooner we realize the necessity of this radical change, the better and more just we can make the situation today, helping all and not just a few receive the full benefits of our technologically advanced society.

Christians, moreover, need to get beyond their defensive support of the necessary relationship between labor and livelihood. Many, to defend an outdated system, like to quote Paul when he wrote, “If any one will not work, let him not eat” (2Thess. 3:10b RSV), as if it answered every question and demanded that we must have a job if we want to eat. However, that is absurd. There are many who cannot work, who deserve respect for their human dignity and should be given food, such as infants to invalids, to those living in places where such work is not available and never will be available again, to those who have lived a long, hard life and are tired and need rest. If the verse meant what some thought is implied with it, infants should be forced to work before they eat; since none of them would work, all of them should be left exposed to nature and perish. They did not work, so they should not eat.

The work ethic, which had some relative value in its time and place of formation, completely misunderstands the bounty of grace. We must work, but the kind of work which we must engage is what is important. We must work, but we receive and participate in that which is greater than what we do in our work. We must work, but the work in Scripture is not the same as a “job.” We must work, but the work is working out our salvation with much fear and trembling; we must work, but we must not be arrogant in our work, assuming that work justifies us and establishes our value. It is not work, it is grace, it is the transcendent bounty, which is of value; our work is the means by which we cooperate with that bounty in the system which has been put in place. The work we must follow is a work of the spirit, not slave labor.

The work Paul wanted us to engage in is the spiritual work all Christians are meant to pursue. The food which they should be after is the spiritual food, the eucharist, which they prepare for through their own spiritual labor. This is the true work which we must do, the work which God expects of us. We must work for our own salvation and then be fed by the grace of the eucharist. Without work, without cooperation with grace, without fighting the spiritual fight within us, casting aside all inordinate passions (such as greed, lust and hatred), we will not eat of the tree of life, we will not find ourselves spiritually nourished, even if and when we partake of communion. “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord” (1 Cor. 11:27 RSV).

This call to spiritually work out our own salvation is a theme found throughout Scripture, found first in the book of Genesis:

And to Adam he said, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife, and have eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, `You shall not eat of it,’ cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. In the sweat of your face you shall eat bread till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Gen. 3:17-19 RSV).

At first glance, this seems to support the work ethic. But reading carefully, it says we must work out in the field, to have the sweat on our brow, if we are to eat. Not many who argue from this verse will suggest only famers should eat, and yet, if they are to take it literally, that is the only conclusion which can come from it. Instead, as with much of what is found in Scripture, the truth lies in the spirit of the text, not the letter. These verses relate with what was said by Paul; it is a declaration that we shall work the spiritual field within, weeding out the thorns and thistles. Since we have fallen into sin, since we have accepted inordinate passions and let them form destructive habits in our lives, we must labor against those habits, sowing in ourselves good, wholesome habits, virtues, while eliminating those vices, those thorns and thistles which grow up in our spiritual soil. Such thorns and thistles, thus, becomes fuel for the fire, to be eliminated as they consumed in the everlasting fire of God’s love, as Origen suggested: “If, therefore, anyone by his failure still remains dry and offers not fruit but ‘thorns and thistles,’ producing, as it were, fuel for the fire, in accordance with those things which are brought forth from himself becomes ‘fuel for the fire.’”[1]

Didymus the Blind, likewise, talked about the spiritual practice being suggested by Genesis. He said that we are to sow in ourselves virtues, realizing how much effort and care it takes for us to develop such virtues: “So the zealous person will find this spiritual grain one with care and effort; when people’s hearts are carefully set on evil, virtue is difficult to pursue and grasped with effort.” [2] We will eat the bread of life with the sweat of our spiritual life, being revived by it. Thus, St. Maximos the Confessor, in one of several interpretations he gave to these verses from Genesis, indicated the spiritual allegory contained within them, pointing out how we must seek spiritual contemplation, which should be our true work:

Or rather, the earth of Adam is the heart, which through the fall was cursed by the loss of the good things of heaven. He “eats” this earth through practical philosophy and by means of “many afflictions” once it has been purged of the curse of the works of shame that burden the conscience. And, again, having removed from this earth the thorns concerning the generation of bodies, and uprooted by the power of reason the arid thistles of his speculations concerning the providence and judgment of bodiless realities, he will spiritually gather up, like grass, natural contemplation. Thus, in the sweat of his face, that is, through true understanding of the mind, he will eat the incorruptible bread of theology, which alone truly gives life and preserves existence in incorruptibility for those who partake of it. The “earth,” accordingly, which is deserved to be eaten, is the purification of the heart through ascetic practice; the “grass” is the true understanding of beings according to natural contemplations; and the “bread” is true initiation into the mystery of theology.[3]

It should not be surprising that so long as the economic system puts undue burden on the poor and downtrodden to sell themselves out for mere trifles in order to survive, they hardly have the time and energy for spiritual labor. God, however, has always demanded the rich give to the poor that which is their due, including freedom from physical burdens so that they can engage God in spiritual contemplation (as the story of the Exodus demonstrates).

The tyrant which demands labor for little food and drink does not want to let God’s people go. The tyrannical system which forces such labor is closing in on itself. There have been all kinds of signs, all kinds of warnings throughout the last few decades. Humanity is about to face a radical shift in the nature of its existence in the world. We are at the beginning of a new spiritual exodus, where the people will be set free. Then the true labor will begin. We shall always work, but the work which we shall do is in and with ourselves. We will be free to pursue truth, goodness and beauty, without the undue burden of earthly tyrants. We shall be free; but if we do not want to take that freedom and turn it into another, greater evil, we must begin to prepare ourselves for that transformation. We need to realize what we can and will be free to pursue once the technological revolution has been completed. We will no longer have to be tied to our jobs; we will be able to truly define ourselves by what we do with ourselves, with the freedom to make that choice. We will have a world of opportunities before us. We will be able to explore, learn, study, produce great works of art, engage with our friends and family in new ways, and all without fear. We will find that the work which inspires us, the work within our spirit which we would like to do but have not been able to do because of social necessities, will now be something we can pursue. For it must be said we will truly be able to work when we no longer have a job getting in the way.

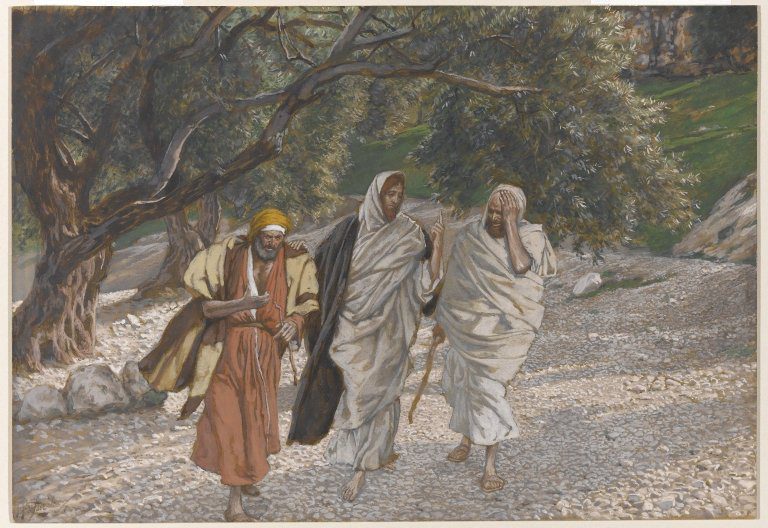

[Image=The Pilgrims of Emmaus on the Road by James Tissot, [No restrictions or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Origen, Homily I on Genesis Homilies On Genesis and Exodus. Trans. Ronald E. Heine (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1981), 51.

[2] Didymus the Blind, Commentary on Genesis. Trans. Robert C. Hill (Washington, DCU: CUA Press, 2016), 102.

[3] St. Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Responses to Thalassios. Trans. Fr. Maximos Constas (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2018), 107.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook