Holding to the teaching that no concept which we have of God can be affirmed in an absolute sense as properly being predicated to God, Dionysius took on the concepts of movement and rest, saying that neither can be attributed to God. Thus, he paradoxically wrote that neither is [God] standing, nor moving; nor at rest. But does that not suggest a contradiction? If God is not moving then he must be standing still or at rest, while if God is not at rest, then is he not moving?

Holding to the teaching that no concept which we have of God can be affirmed in an absolute sense as properly being predicated to God, Dionysius took on the concepts of movement and rest, saying that neither can be attributed to God. Thus, he paradoxically wrote that neither is [God] standing, nor moving; nor at rest. But does that not suggest a contradiction? If God is not moving then he must be standing still or at rest, while if God is not at rest, then is he not moving?

Both the concepts of movement and rest end of misconstruing God if we take either of them as reflecting who and what God is in the absolute sense, while both of them can be affirmed, in a relative sense. Both movement and rest are understood by us in relation to temporal existence. Movement is measured by the change which occurs over time (especially, and normally, the change of location). Movement indicates activity and the lack of movement indicates the lack of activity, so that there is a sense of stasis or rest when movement is lacking. A subject which is at rest has no measurable forms of activity which can be attributed to them.

God, therefore, is not moving, because he is outside of time and place. And yet, when it is said that God is not moving, this suggests he is standing still and at rest. That is, God does not appear to be an active subject. Not being an active subject, God would have no active engagement with others. In this fashion, God would end up having no influence on the temporal order. The unmoved subject absolutely at rest would not be a mover, but rather, would be completely unmoving, having no causal relationship with anything or anyone else. Nonetheless, God is the creator of everything; he is the agent by which all creation exists. He must not be seen as moving within time, but he is an active agent who exists outside of time, whose agency affects the whole created order. In this fashion, because he is an active agent, God transcends what we conceive of immobility by being active, while he transcends what we conceive of mobility because he is outside of time and space. He is the unmoving agent who transcends all sense of change. As an active subject, there is nothing which moves him or forces him to act; there is no change in him, and yet there is an eternal unchanging divine activity from which all creation, all contingent being flows.

St. Maximos the Confessor, reflecting upon this paradox, explained it similarly:

In the same way, the Divine by essence and nature is completely unmoved, insofar as it is boundless, unconditioned, and infinite, but not unlike a scientific principle that exists within the substances of beings, it is said to be moved, since it providentially moves each and every being (in accordance by which each one is naturally moved), and as the cause of beings, it may receive – without suffering any change – all the attributes of the beings of which it is the cause. [1]

We must deny God is mobile, that God is moving, because God is neither in time nor subject to change. But we must also deny what denial of mobility suggests about God. That is by denying mobility, it suggests he is not a free subject but rather like an inanimate object without will, without activity. God remains free, and with his will, he acts and generates creation, but he does so in a way which transcends our understanding of activity when our comprehension of activity is founded upon temporal movers.

Proclus, in his Elements of Theology, understanding this point, suggested that eternal actions must be seen as activity without change:

If its activity be eternal in addition to its existence, this too is simultaneously entire, steadfast in an unvarying measure of completeness and as it were frozen in one unchanging outline, without movement or transition. [2]

Time is finite, while God’s eternal activity is infinite; that infinitude of God’s action, when encountered in time, might make it seem that God is changing, but that is because of us and not God. If someone could see into eternity and outside of time, they would be able to perceive the unchangeable quality of God’s activity and so would have no problem understanding his activity to be from his unchanging eternal will.

Our concept of action causes us to be confused when we say God is not mobile; to affirm God’s free agency, Dionysius had to deny our concept of activity as a whole. He did this by denying God is mobile while denying God is at rest: he is neither, because both concepts reflect subjects under the domain of time. His denials, then, deny the conceptual framework which we normally use to understand the cosmos. When we try to apply that conceptual framework and use it in speaking about God, we establish notions which infringe on the character of God. Dionysius can be shown to be moving us away from all discursive reason by showing how our logical distinctions fail. As Robert Grosseteste indicated, motion and rest are seen “disjunctively” in relation to those things which exist in creation,[3] so that something is either active and an agent, or inactive and merely objective; both of these must be denied for God because he is an agent who is active in a transcendent fashion. God is active without ceasing and yet his activity itself is one which does not change. Our denials deny the dualistic way in which we construct our vision of the world, a dualism which is always implicit in the words and concepts which we use to describe God.

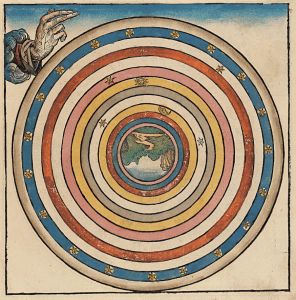

[IMG=Hand of God Creating the World from the Schedelsche Weltchronik or Nuremberg Chronicle. Scan by Hartmann Schedel (Self-scannedlanguage: Latin) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] St. Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua. Volume II. Trans. Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 5-7.

[2] Proclus, The Elements of Theology. Trans. E.R. Dodds (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963), 51.

[3] See Robert Grosseteste, “De Mystica Theologia” in Mystical Theology: The Glosses of Thomas Gallus and the Commentary of Robert Grosseteste on De Mystica Theologia. Trans. and ed. By James McEvoy (Parish: Peeters, 2003), 115.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook