Tolkien in the opening section of The Silmarillion, the Ainulindalë, presents an explanation for evil which arose from his aesthetic understanding of creation. He shows the superiority of the good over evil by the way good can take evil, harmonize with it, and make a greater good as a result; that is, good is able to grow strong, more beautiful, as it struggles with evil and overcome it, while evil is unable to indefinitely oppose the good. As discord can be harmonized with and produce something greater, some thing more beautiful, so the discord which evil brings about can be overcome in order to produce some greater, more beautiful good. There is a symphonic structure to creation; history reveals the symphony in progress, with evil seen in the dark notes of distress. And yet, when contemplated as a whole, history, like a great symphony, is to be understood only after it is over, and there we find it ends not with sorrow and despair, but with hope. Even that which is used to resist God comes from some good given by God. That is, what produces evil nonetheless has some element of good remaining within it, an element which comes from God and which God can draw upon and use to bring about his desired end. For this reason, Melkor, the Satanic figure in Tolkien’s myth, was told how his resistance itself only works for Ilúvatar ‘s greater purpose (with Ilúvatar being one of the names for God in Tolkien’s myth):

Tolkien in the opening section of The Silmarillion, the Ainulindalë, presents an explanation for evil which arose from his aesthetic understanding of creation. He shows the superiority of the good over evil by the way good can take evil, harmonize with it, and make a greater good as a result; that is, good is able to grow strong, more beautiful, as it struggles with evil and overcome it, while evil is unable to indefinitely oppose the good. As discord can be harmonized with and produce something greater, some thing more beautiful, so the discord which evil brings about can be overcome in order to produce some greater, more beautiful good. There is a symphonic structure to creation; history reveals the symphony in progress, with evil seen in the dark notes of distress. And yet, when contemplated as a whole, history, like a great symphony, is to be understood only after it is over, and there we find it ends not with sorrow and despair, but with hope. Even that which is used to resist God comes from some good given by God. That is, what produces evil nonetheless has some element of good remaining within it, an element which comes from God and which God can draw upon and use to bring about his desired end. For this reason, Melkor, the Satanic figure in Tolkien’s myth, was told how his resistance itself only works for Ilúvatar ‘s greater purpose (with Ilúvatar being one of the names for God in Tolkien’s myth):

Then Ilúvatar spoke, and he said: ‘Mighty are the Ainur, and mightiest among them is Melkor; but that he may know, and all the Ainur, that I am Ilúvatar, those things that ye have sung, I will show them forth, that ye may see what ye have done. And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined.’[1]

This aesthetic understanding, beautiful within the context of Tolkien’s myth, represents the way the Christian tradition has understood how God deals with evil. There is nothing which is fundamentally evil in itself. Evil is a corruption of the good, a parasite which thrives upon the good, and people are attracted to evil not because it is evil but for the limited good which they sense from it. Likewise, that good remains open to union with the rest of the good, to harmonize with the rest of the good, so that it can establish a new good, a greater good than what existed before. This is not because evil is vindicated and is accepted, but because the good is able to draw upon the good found in evil, to take what is in it, to take what is given to it new, and to grow and thrive, in the way contrasts in music establish a greater, more aesthetically pleasing composition. This is not to say evil is good and should be accepted; rather this is to say that evil does not have the final say and the good which it uses to establish itself can become its own undoing.

Marsilio Ficino, following Plotinus and Proclus and other Platonists, not only understood the relationship between discord (or disharmony) with evil, but also the way evil had at its core its own undoing:

Rather, evil is in a certain disharmony of those things among themselves which people call “asymmetry”: that is, incommensurability. In so far as it relates to bodies, evil is not in form, for the latter wishes to dominate matter. Again, evil is not in matter, since the latter seeks to be adorned. It is rather in a certain unsuitability to form on matter’s part. From this, Proclus concludes that every evil is a quasi-existent and that whatever exists in this residual sense, coming suddenly and stealing into the creative work of the Good, is tinged with divinity. Given that the realm of generation exists, this evil also necessarily exists beneath it contributing to the perfection of the world but, with divine providence overcoming all things and wishing good things, is wonderfully made conformable to the Good. [2]

Evil, in its disharmony, tries to break apart and destroy what exists. Nonetheless, its own tools come not from itself but from what already exists, that is, from what is good. Not only did God establish creation, there is a sense in which all that exists participates in God’s super-essential existence, so that all things can be said to be “tinged with divinity.”

In this fashion there is a mysterious providence over history which will be revealed in the eschaton by the way God reconstitutes creation, bringing it all together as one in the revelation of the kingdom of God. There is tragedy and sorrow involved in history and in the establishment of the kingdom of God because of free will and contingency, and yet God knew that from such sorrow there could emerge something greater, something more blessed, something more thriving and alive than if he created a universe without free will. What good is there in the establishment of automatons? Perhaps, a little, but it is an inferior good which God does not seek. God wants a greater good, a good which manifests itself in love. And if it is in love, then it must follow the way of love: love does not force itself upon the beloved; it does not coerce, it frees and lifts up the beloved. Creation is established to participate in divine love, to be filled with life; it is given freedom and finds its best, truest freedom when it is in the kingdom of God. As Sergius Bulgakov explains, the kingdom of God is not inert, is not some lifeless dead-end, but it is the true realization of life and creative activity:

The kingdom of Christ becomes the kingdom of all-conquering universal goodness, which grows toward eternal life not only by personal effort but also in the union and sobornost of the universal Church. Thus, for creation, eternity does not signify the abolition of temporality with its becoming. Eternity is not an inert immobility but an inexhaustible source of creative life.[3]

The kingdom of God reveals the restoration of all things. The good unites and reveals its glory to us so that we find it attractive through its beauty. Evil distorts this; it attracts us, to be sure, through a distortion of the good. The more we fail to follow the good, the more we sin, the more the distortion overtakes our awareness. “Evil is nothing but spiritual distortion, and sin is all that leads to such distortion.”[4] As the good draws us in, as it brings is to a new, greater harmony, even the wounds which we experienced as a result of such distortion can be healed. That is to say, we not only have something greater as a result of human freedom, but even the burdens and sorrows caused by evil can be healed, so that no place, not even the fires of hell, can overcome the good, as Sergius Bulgakov also recognizes:

And since redemption is accomplished not only by the sacrifice of the Son sent by the Father, but also by the Holy Spirit, healing the sores of creation, the Holy Spirit continues its work of healing and restoration as long as that which is unhealed and unrestored remains. And the Holy Spirit can penetrate even the doors of hell.[5]

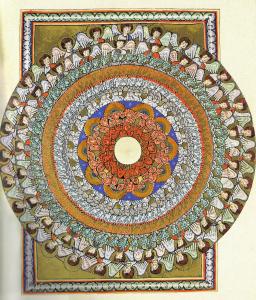

Medieval representations of the kingdom of God as a choir, with angels and saints signing together, do not have to be taken literally. Rather, they serve to represent, through an aesthetic analogy, the glory which is to be had in heaven. Music has the power to uplift those who hear it. St. Hildegard, understanding this by her own work with music, was able to represent the eschaton as a harmonious, beautiful choir. As the sound which is made transcends the singers as it fills a room with music, so God’s power and glory can be understood to be everywhere present and filling all things; those harmonizing themselves with God will find themselves filled with vitality, aroused beyond all forms of sloth: “And as the power of God is everywhere and encompasses all things, and no obstacle can stand against it, so too the human intellect has great power to resound in living voices, and arouse sluggish souls to vigilance by the song.”[6] And this is done through the work of the Good Shepherd, who like a conductor, is able to harmonize diverse elements and bring them together in a beautiful whole:

And you hear another song, like the voice of a multitude breaking out in melodic laments over the people that have been brought back to that place. For the song does not only harmonize and exult over those who persevere in the path of rectitude, but also exults in the concord of those who are resurrected from their fall out of the path of justice, and are at last uplifted to true beatitude. For the Good Shepherd has brought back to the fold with joy the sheep that was lost.[7]

And so, as Ficino discusses in his works, whatever comes about in history, whatever evil which is done, leaves behind a good which can be taken in by God for the completion of his plan for creation; that everything which is done in contingency still has a place in the eschatological order of the universe: “Meanwhile, whatever is born or arises as harmful or evil with respect to certain things is not permitted to come about otherwise than as being useful and as a good toward many other things and as otherwise than as fitly completing the order of the universe.”[8] The glory of the kingdom of God is the beautiful glory of the good in which the good reveals itself superior to all resistance to itself. The good conquers evil from within evil itself, showing that at the heart of all such evil, there remains some good which can once again be integrated into the whole

“The righteous who have comprehended the world in its truth and beauty will not gaze on hell at all, for it does not exist in the eyes of God either.”[9] In the eschatological vision of the blessed, they will see this good in all things; no longer will hell itself be a threat for them because they will see that hell itself has been overturned by God. It does not truly exist; its nature is that of evil, and evil does not exist. Only good exists, in various forms and gradations. The effects of evil will be remembered; the distortion of the will by which we sinned will be remembered, but in that memory, we can find healing grace to lift is up beyond the damage which we have done. And then, hopefully, we will see God’s providence is at work, harmonizing us with God’s eschatological goal so that all that remains before us is the beautiful kingdom of God.

[IMG= Vision of the Angelic Hierarchy by unknown [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1977), 17.

[2] Marsilio Ficino, Commentary On Plotinus: Volume 4. Ennead III, Part I. trans. Stephen Gersh (Cambride: Harvard University Press, 2017), 143.

[3] Sergius Bugakov, Bride of the Lamb. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans’ Publishing Company, 2002), 481.

[4] Pavel Florensky, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth. Trans. Boris Jakim (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 192.

[5] Sergius Bugakov, Bride of the Lamb,515.

[6] St. Hildegard of Bingen. Scivias. Trans. Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop (New York: Paulist Press, 1990), 533.

[7] St. Hildegard of Bingen. Scivias, 533.

[8] Marsilio Ficino, Commentary On Plotinus: Volume 4. Ennead III, Part I, 133.

[9] Sergius Bugakov, Unfading Light. Trans. Thomas Allan Smith (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans’ Publishing Company, 2012), 431.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook