Alexander Schmemann noted that our relationship with God will be manifest in the way we give him glory through our thanks. Thanksgiving is the state of the perfect, of those who truly love God and recognize the great gifts he has given us, including and not limited to, the forgiveness of our sins. That means, as Jesus is himself the perfect man, he himself gave the most perfect thanksgiving, making him the one true thanksgiving, the one true eucharist, by which and through which we can render our eternal thanksgiving to God:

Alexander Schmemann noted that our relationship with God will be manifest in the way we give him glory through our thanks. Thanksgiving is the state of the perfect, of those who truly love God and recognize the great gifts he has given us, including and not limited to, the forgiveness of our sins. That means, as Jesus is himself the perfect man, he himself gave the most perfect thanksgiving, making him the one true thanksgiving, the one true eucharist, by which and through which we can render our eternal thanksgiving to God:

When man stands before the throne of God, when he has fulfilled all that God has given him to fulfill, when all sins are forgiven, all joy restored, then there is nothing else for him to do but to give thanks. Eucharist (thanksgiving) is the state of perfect man. Eucharist is the life of paradise. Eucharist is the only full and real response of man to God’s creation, redemption and the gift of heaven. But this perfect man who stands before God is Christ. In Him alone all that God has given man was fulfilled and brought back to heaven. He alone is the perfect Eucharistic Being. He is the Eucharist of the world. In and through this Eucharist the whole creation becomes what it always was to be and yet failed to be.[1]

Jesus is the eucharist; in his humanity he offers the perfect thanksgiving, rendering over his whole self over to the Father in an act of incomprehensible love. We, who experience the grace and glory of God, also want to give to the Father that same thanksgiving. To do this we partake of the one universal eucharist of Jesus. We partake of him and become one with him, allowing us to offer ourselves over to God with the true thanksgiving which we wish to give to him. This is how and why we can render to God our loving thanks despite all our sins. We are joined into Christ: we partake of him as he takes us into himself, allowing us to become one with his body, sharing in the bounty of his perfection, including and especially, the perfection of his thanksgiving to the Father.

By ourselves, we would never be prepared for this: we would always be far from the perfection of Christ; we can look ourselves and say we are unworthy; but yet, in and through love, we can be justified. In and through love we give ourselves over to Christ and become one with him:

The early Church knew that, in all creation, there is no one who is worthy through his own spiritual effort, through his own “worthiness,” to partake of the body and blood of Christ, and that therefore the preparation consists not in a calculation and analysis of one’s “preparedness” or “unpreparedness,” but in the answer of love to love…[2]

Even before we realize in love our desire to give thanks to God, Jesus calls us through his love to partake of his life, of his thanksgiving to the Father. He is the light and life of humanity; in him is eternal life, true life, true joy and love, which returns to the Father true thanksgiving. Even when we are sinners, we are called to that thanksgiving banquet, that universal and eternal thanksgiving, to partake of Christ and become one with him and his eucharist. When we heed the call and repent of our sins, he gives us his flesh and blood as true food and drink, for they give us life and allow us to become one with him. We are called to become the body of Christ, to be incorporated into Christ, and we do this through our communion, where we become one with him and with everyone else who so joins with him. We partake of the gifts he gives us; we share in his life, a life of love. All the graces which flow from communion raise us up and deify us so that through them we become partakers of the divine nature. Through communion, heaven and earth are united: all things become shared by all for all and through all. For, as St. Albert the Great explained, communion brings us into contact with all that is in heaven, such as the angels and saints, and all that is on the earth, so that all of us share the glory of God in common:

Therefore, it is placed in this genus on account of seven [aspects of] communion that it brings about in us: for it causes communion in the fount of all graces, it causes communion in the glory of the angels, it causes communion with the saints, it causes communion in the sufferings of the mystical body, it causes material assistance in works of mercy, it makes all that is ours common, it causes the truest communion of the divine and human, and therefore it is called “communion.”[3]

Communion, the eucharist, brings all together into a universal love. The graces are shared in common. Those who realize communion in their lives do so in a way where they no longer look at the world as “mine” and “thine.” They do not selfishly seek glory for themselves at the exclusion of others. Rather, they seek to share what they have with others, for that is what life in Christ entails. We become one with him and so we share in his universal love for others. By giving we grow and gain even more graces, while trying to hold it all onto ourselves will cut it off and we will lose it. “One man gives freely, yet grows all the richer; another withholds what he should give, and only suffers want” (Prov. 11:24 RSV). We have a new relationship with others. We no longer look at them as divided from us, but rather, we see them united with us, and their benefit is our benefit.

Thus, it can be said that communion teaches us no longer to look at the world with a dualistic vision of division, seeking to make things exclusively mine or thine, but rather, it sees beyond all such division, to see our relational existence with others unites us with them without losing ourselves in the process. This is why Alexander Schmemann could say, “There can be no doubt that in the ‘spirituality’ of early Christianity the ‘communal’ reinforced the ‘personal,’ and the ‘personal’ was impossible without the ‘communal.’” [4] We die to the self to be raised up and resurrected in communion, to truly become who we are meant to be as persons related to and united to each other. Likewise, this is why St. Albert the Great was able to say that communion led us to engage corporate works of mercy. What is earthly has been transformed for us and so we no longer look at the world with greedy eyes, but rather with such a thankful heart, we want others to share in our bounty:

For this communion causes material assistance in the works of mercy, since he who has resources freely supplies them so that he may receive an abundance of spiritual [goods] from the whole body in return for temporal [goods]. So [Rom 15.27], “If the Gentiles have been made partakers in their spiritual goods,” that is, of the saints, “they ought in carnal things to minister to them.” For this is the communion in the one body of Christ.[5]

Even if we have no material goods, we still want to help others, and so in that thankful spirit, we do so:

For this communion causes various helping works. [Rom 15.1-2] “Now we who are stronger ought to bear the infirmities of the weak, and not please ourselves. Let every one please his neighbor for good, for edification.” [Gal. 6.2] “Bear one another’s burdens; and so you shall fulfill the law of Christ.” [6]

Communion joins us with Christ. Through it, we become the body of Christ, and continue the work of Christ in the world. When we act out of selfishness, we cut ourselves off from that communion. Avarice, hatred, inordinate desires all seek to have us lift ourselves up above others, caring not for their suffering and burdens, and as we embrace such root evils, so we find ourselves falling out of communion and the life of thanksgiving and praise which is the life of the Christian. We are called to share the great banquet of Christ, his eucharist. We must open ourselves up to him so that he can then incorporate ourselves to him. We are to share his life. We are to share his glory. We are to share his joy. We are to share his love. We are to share his thanksgiving. And so we seek to bring others into this great universal thanksgiving feast, to have them united with us in a love so great, nothing can stand in its way. For through it God is rendered all in all:

For this communion causes the truest communion of the divine and the human. For in it, God with all his goods is in man, and man in God, and God and man have this relation in all of us, so that what is said is true [1 Cor 15.28], “that God may be all in all.” For God stoops down to us in this communion, and lifts up our humanity into himself, and this was frequently desired and prayed for by the ancient fathers.[7]

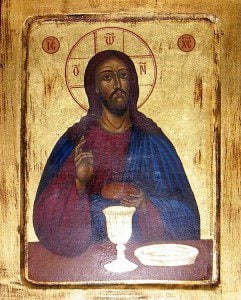

[IMG=Jesus’s Mystical Supper. Icon owned and photographed by Henry Karlson]

[1] Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2002), 37-8.

[2] Alexander Schmemann, The Eucharist. Trans. Paul Kachur (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1987), 241.

[3] St. Albert the Great, On the Body of the Lord. Trans. Sr. Albert Marie Surmanski, OP (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2017), 263.

[4] Alexander Schmemann, The Eucharist. Trans. Paul Kachur (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1987), 241.

[5] St. Albert the Great, On the Body of the Lord. 272.

[6] St. Albert the Great, On the Body of the Lord, 272.

[7] St. Albert the Great, On the Body of the Lord., 276.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook