“It is self-evident that there is no comparative relation of the infinite to the finite,” Nicholas of Cusa wrote.[1] “Therefore, it is most clear that where we find comparative degrees of greatness, we do not arrive at the unqualifiedly Maximum; for things which are comparatively greater and lesser are finite; but, necessarily, such a Maximum is infinite.”[2] For this reason, though we remain ignorant of the absolute as it is in itself, we nonetheless have an infinite possibility in regards to our progression towards the absolute. The more we know, the more we can compare what we know to what we did not know, and see we have attained a greater grasp of the truth, but in doing so, we find ourselves only at a relatively greater position while still infinitely distant from the absolute itself. This, then, shows we can talk about knowledge and learning, agreeing that some people know more than others, having apprehend greater truths than others because there is an absolute truth from which all relative truth flows. On the other hand, all such learning and knowledge remains on the level of “ignorance” in comparison to the absolute truth as it is in itself, because the absolute truth remains incomprehensible. We are, in a relative sense, apprehending the truth: we are not nihilists. What we receive as we apprehend the truth comes to us in many possible forms, many possible symbols which participate in the truth even as they point to the absolute truth which lies beyond them.

“It is self-evident that there is no comparative relation of the infinite to the finite,” Nicholas of Cusa wrote.[1] “Therefore, it is most clear that where we find comparative degrees of greatness, we do not arrive at the unqualifiedly Maximum; for things which are comparatively greater and lesser are finite; but, necessarily, such a Maximum is infinite.”[2] For this reason, though we remain ignorant of the absolute as it is in itself, we nonetheless have an infinite possibility in regards to our progression towards the absolute. The more we know, the more we can compare what we know to what we did not know, and see we have attained a greater grasp of the truth, but in doing so, we find ourselves only at a relatively greater position while still infinitely distant from the absolute itself. This, then, shows we can talk about knowledge and learning, agreeing that some people know more than others, having apprehend greater truths than others because there is an absolute truth from which all relative truth flows. On the other hand, all such learning and knowledge remains on the level of “ignorance” in comparison to the absolute truth as it is in itself, because the absolute truth remains incomprehensible. We are, in a relative sense, apprehending the truth: we are not nihilists. What we receive as we apprehend the truth comes to us in many possible forms, many possible symbols which participate in the truth even as they point to the absolute truth which lies beyond them.

Whatever is positive, good, and beautiful, represents in its own way, the truth of God. They can and do serve as symbols for God. They are works of God which cry out concerning the truth of God: if we listen, they will serve us well as they point to God as the foundation and source of all being. God shares himself with creation by establishing creation itself, allowing creation therefore to represent him. All things reveal the glory of God, and all things can serve as revelation pointing to the truth of God, allowing us to discuss God in and through them. The greater the glory, the greater the nature being discussed, the more it opens itself up to and allows itself to be used to represent God. Scripture invokes many images for God in this manner. As St. Edith Stein explained, such images can be confusing, indeed, confounding to those who do not read them properly.[3]

Images of God being angry or drunk or asleep all represent something about God which God wants us to understand, but we must come to them, not seeking them to represent the absolute truth as it is in itself but as a relative convention helping us to become aware of that truth. As we wrestle with images revealed to us as representations of the absolute truth, we will find many of them disconcerting, thinking they take us away from the truth, because we want to read them either literally or as absolutes in and of themselves. Only when we look for the spirit behind the words, to see what is intended by them, do we begin to appreciate how they properly point to and represent something concerning the absolute truth in a way which we can conceive it.

Nonetheless, we find Scripture not only using concrete images and things in the world to represent God, but also abstract qualities of being to represent the absolute. When engaging them, we must remember that they, too, are conventions. Kataphatic theology often goes through such abstract representations of God, seeing how they free us from cruder conceptions of God, as a way to move us away from a simplistic understanding of God which tries to tie him to our understanding to a greater appreciation of God’s transcendence. God is able to be said to be being, eternity, truth, glory, beauty, and goodness, not because God is comprehended by such names, but because they (among others) represent the greatness of God better than their opposites. Yet, as Dionysius understood, as there is nothing which can stand in opposition to God, these terms are also relative and limited in representing God: the fact that they can be opposed demonstrates their relative nature and why the absolute is not contained in them. Even the title, God, represents a concept of being which can be opposed (through atheism), and so is far less than what the absolute is in itself, though God is the proper title insofar is we understand its relative use to represent the one transcendent cause of all things. This is why we can be called to become gods without confusing us with the absolute in itself: godhood represents all kinds of conditions in the realm of being (great power, great intellectual insight, immortality) which is less than what we find in the absolute itself. The absolute established these qualities of being, and so transcends them. In this way, the absolute is above Godhood, even as it transcends the Good, as Dionysius explained in his second letter:

How is He, Who is beyond all, both above source of Divinity and above source of Good? Provided you understand Deity and Goodness, as the very Actuality of the Good-making and God-making gift, and the inimitable imitation of the super-divine and super-good (gift), by aid of which we are deified and made good. For, moreover, if this becomes source of the deification and making good of those who are being deified and made good, He,—-Who is super-source of every source, even of the so-called Deity and Goodness, seeing He is beyond source of Divinity and source of Goodness, in so far as He is inimitable, and not to be retained—-excels the imitations and retentions, and the things which are imitated and those participating.[4]

When kataphatic theology discusses that there can be only “one God,” it is using the term God to point to the transcendent absolute. No one will become the absolute, and so no one will become God in the way the term is used to represent that absolute. But that absolute lifts us up, and makes us great, so that in and through grace, we partake of the absolute and are transformed by it, partaking of eternal life. This participation allows us to be called “gods,” realizing that it is not something which makes us the absolute; rather, we remain relative creatures who participate and experience the absolute constantly making us greater, drawing us further in to its greatness. Just as there is “one Good” in which all goods come from and participate in, so that those multiple goods do not negate that one “Good,” so there is “one God” and yet multiple ways of participating in that Godhood which makes those who participate in it capable of being said to be gods. The Absolute, being beyond all being, grants goodness to us, and in that goodness, we find ourselves transformed and participating in Godhood, allowing us to become gods by participation while remaining far from “the One God.” Likewise, insofar as the absolute transcends all relative affirmations, therefore all who are made good and holy, all who are said to be deified by God, remains infinitely less than what the absolute is as it is in itself: God, when used as a term to represent the absolute, is not to be confused with those who have been made gods by grace. The absolute transcends goodness and divinity, and is incapable of being imitated by anything in the realm of being, even goodness and divinity itself can be said to be things which it has made, which is why they can be imitated by creatures. Yet, because we know how to use symbols to point to objects beyond the letter being expressed (as those who have learned algebra can do with ease), so we can still use the term God as a pointer to represent the absolute, in our discussions of the absolute, though we must always caution those who read us not to confuse the term with some relative being when we do so (which is always a temptation, no matter how great a being we end up granting to the divine nature).

One key distinction between those who are “made gods” by the absolute’s deifying ways, and the absolute, is that only the absolute is without cause, without anything which makes it as it is. The absolute is capable of being said to be God, not in the way which those which are made gods are called god. The term is the same, and comes from kataphatic theology with its relative truths, but nonetheless hinted behind it, is the fact that all things which exist, all things which are deified, cannot be deified by themselves: they need the absolute to be the source and foundation for their theosis, even as it is the source and foundation for their goodness. We are to be holy as God is holy, because we are to be made good through grace. We are by nature called to be good, and said to be good in a relative sense due the goodness of being itself being granted to us by the absolute cause of all things, but we must recognize even that this relative goodness is not something we established for ourselves but have been given by the absolute. This, Andrew Louth, understood was an important theme in the works of Dionysius: the goodness, the grace, the light, the being, godhood itself, is all something that is “received and passed on.”[5] This shows us the relative quality of goodness as it exists in us: it is not absolute, and so we can’t be called” the good,” but only good as we participate in the good. The more we participate in the good, the more we find it granted to us and infused in us as a gift of the absolute.

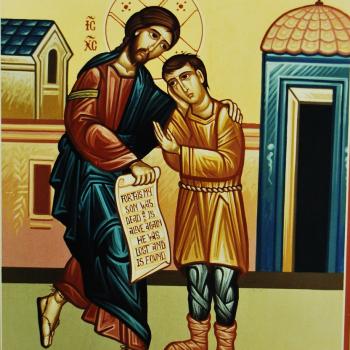

[IMG=Deytera parousia_decaniarousia by Unknown author [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Nicholas of Cusa, On Learned Ignorance. Trans. Jasper Hopkins (Minneapolis: Arthur J Banning Press, 1985; 2nd corrected edition 1990), 52.

[2] Ibid., 52.

[3] “Holy Scripture is full of such bold images that may offed those who fail to understand them. But the person who can see the beauty hidden beneath the image will find them full of God-revealing light,” St. Edith Stein, “Ways to Know God” in Knowledge and Faith. Trans. Walter Redmond (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 2000), 90.

[4] Dionysius, “Letter Two” in The Works of Dionysius the Areopigate. Trans. James Parker (London: James Parker and Co,, 1897), 141-2.

[5] Andrew Louth, Denys the Areopagite (Wilton, CT: Morehouse-Barlow, 1989), 40.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook