In one of the most important revelations concerning the nature of God in Scripture, God revealed to Moses the name which Moses should use to represent him to the people of Israel:

In one of the most important revelations concerning the nature of God in Scripture, God revealed to Moses the name which Moses should use to represent him to the people of Israel:

Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, `The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, `What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I AM WHO I AM.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel, `I AM has sent me to you.'” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel, `The LORD, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you’: this is my name for ever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations (Ex. 3:13-15 RSV).

While there is no name, no word, no title, no thought which can absolutely represent God as he is in himself, there are many names and titles which God gives to us which fittingly reveal something of his transcendent greatness. The tetragrammaton, יהוה, the name often transliterated as YHWH, is most fitting for God because of how it represents because of the mysterious ambiguity contained in the meaning of the name itself. For, often seen as indicating “I am who I am”,” it really fits not only the present, but also the past and future tenses for the word to be (indeed, the present tense of it has to be extrapolated as part of the intended meaning as the Hebrew). What is said, therefore, could “I will be what I will be” as well as “I was as I was” even as it can be read to indicate “I am that I am.”

Implied in all this is that the name of YHVH is somehow related to being; the ambiguity in relation to the word related to being can be seen to indicate the way God transcends time and only has himself for his being. There is nothing which constrains him; all that he is, he was, is, and ever shall be. If we want, we could read God as also saying “I am what I will be,” “I am as I was,” “I will be as I am,” and “I will be as I was.” While these readings are not normal can be seen as a stretch, they follow with the implied meaning given out with the name, that is, God is the great I am in a way which is unrelated to time or dependency upon others. He is and ever shall be: time does not touch him; whatever he is, he is.

This revelation is what gave authenticity to Moses; but it is not just the name itself, but the significance in the name, the implied secrets to the name, which makes the name authentic, as Elijah Benamozegh explained:

The true believer is the one who possesses the inner meaning of the divine names; for it is clear that if comprehension of their authentic sense is lacking, it is not the true God but a false approximation which is being worshiped. Moreover, the expression “to know the name of God” means in the Bible to possess true religion, and the rabbis used analogously the expression “handing down of names” to denote the teaching of religious doctrine. Among the ancients, theological speculation was not isolated from the practical application of words. This assumption of the sages that the divine names contain Israel’s theological knowledge explains why Moses, in God’s presence, insists upon knowing His name so that he might be able to provide evidence of the authenticity of his mission.[1]

It is not the letters but the mystery represented by the letters which makes the tetragrammaton so significant. The mystery is why this name given for God would traditionally not be said: the name is an authentic revelation of God, but it is easily converted into an absolute, limiting God by the name, and turning God into a thing trapped which could be comprehend by mere human letters. To know the name is important: but to know the name includes recognizing the mystery behind the name, and not just the literal letters used for the name itself. The ambiguity behind the meaning of the name represents the mystery of God; we can find many meanings and apply them in our theological reflections (many of which surround the notion of being and God’s relationship with being), but what seems to be overlooked are the ways the name indicates something about God’s relationship with time. God’s being is timeless, and this is best represented in the ambiguity in relation to the sense of time associated with being in the text. His being is not just a thing of the past, nor of the past and present, but is can be said to be there already existing in the future: his activity encompasses all time. It is easy to think of God’s action as being over: God “rested” on the seventh day, but in doing so, we put him out to pasture, to the past which only indirectly affects us. We can think of him active in the present, though what we should also be attuned to is that he is not just active in the past or present, but he is also coming to us from the future, so to speak. His eternity brings us to him in the future even as we encounter him in the present and see him in the past. Abraham Isaac Kook saw in this a revelation of the transcendence of God: by being active in the future and coming to us from there, he is not trapped in the present with all its limitations:

However, the Jewish religion is rooted in the Infinite, which transcends every particular content of religion, and for this reason the Jewish religion may truly be considered as the ideal of religion, the religion of the future, the “I shall be what I shall be” (Exod. 3:14), what is immeasurably higher than the content of religion in the present. [2]

Christianity, likewise, understands this aspect of religion, this future sense which must be included, through its eschatological understanding of the second coming of Christ. Christ is with us even unto the end of the world, even as he comes to us from that end and meets us in the present from that end. The eschaton has become immanent even as we find ourselves moving towards the eschaton in time. In the tetragrammaton, we receive, therefore the sense of the infinite transcendence of God, not only in his relationship with being, but with time, making it a fit representation of God, authenticating the power and authority of Moses and his prophetic ministry. [3] St. Gregory of Nyssa, realizing this, saw the greatness of Moses’ encounter with God as it moved him out of himself, out of his normal ways of knowing and seeing thigs, so that he could see and understand the greatness of God by seeing he is the one in whom, from whom, of whom, everything outside of him depends:

It seems to me that at the time the great Moses was instructed in the theophany he came to know that none of those things which are apprehended by sense perception and contemplated by the understanding really subsists, but that the transcendent essence and cause of the universe, on which everything depends, alone subsists. [4]

In relation to God, nothing else is; he is alone the one who can be said to be because he alone is what he is, outside of all limitations, including time. God revealed himself to Moses, who, transformed in the meeting with God, was able to portray that through the name God revealed which represented this truth to the people of Israel (and all others who would listen and learn from Moses). God is – YHWH. There is no other.

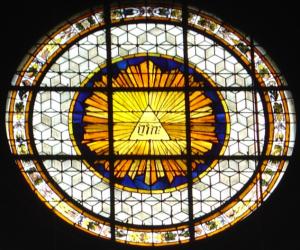

[Image=Tetragrammaton at the Roman Catholic Church Saint-Germain-des-Prés, at Paris, France By Pvasiliadis (Pvasiliadis’ foto) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Elijah Benamozegh, Israel and Humanity. Trans. Maxwell Luria (New York: Paulist Press, 1995), 115.

[2] Abraham Isaac Kook, “The Pangs of Cleaning,” in Abraham Isaac Kook: The Lights of Penitence, Lights of Holiness, The Moral Principles, Essays, Letters and Poems. Trans. Ben Zion Bokser (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 267.

[3] Prophecy by its nature is not limited to time, which is why it is often hard to read and understand what is being portrayed by a prophet, especially when they write in an apocalyptic style. The past can be seen confused with the future, which his exactly what is to be expected with an encounter with that which transcends time.

[4] St. Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses. Trans. Everett Ferguson and Abraham J. Malherbe (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 60.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook