In the Mystical Theology, Dionysius taught us about our apprehension of the truth, reminding us not only of our limitations in regards to the declaration of the truth, but also that proper engagement of the truth will be had in and through our union with it. Central to his discussion is that the absolute truth, which we name as God (and many other, similar names, related to our notion of divinity), transcends us and so will never be comprehended by us. For our goal, we hope to be lifted up outside of ourselves as we find ourselves dwelling within and communing with the truth itself. Whatever we posit of the truth in our words, whatever we think about it in our thoughts, can never be what the truth is in and of itself.

In the Mystical Theology, Dionysius taught us about our apprehension of the truth, reminding us not only of our limitations in regards to the declaration of the truth, but also that proper engagement of the truth will be had in and through our union with it. Central to his discussion is that the absolute truth, which we name as God (and many other, similar names, related to our notion of divinity), transcends us and so will never be comprehended by us. For our goal, we hope to be lifted up outside of ourselves as we find ourselves dwelling within and communing with the truth itself. Whatever we posit of the truth in our words, whatever we think about it in our thoughts, can never be what the truth is in and of itself.

Yet, it is important for us to realize that we can and will apprehend the truth, allowing us to speak of it, so long as we realize the relative value of the convention we use in order to talk about it. Our relative presentation of the truth is capable of being said to be true so long as it comes out of and is tied to the absolute truth. We must find ourselves connected with and penetrated by the absolute truth if we want to confirm the value of our conversations about God. We can properly talk about the truth when we experience it for ourselves.

What is it that prevents us from finding ourselves to be united with the truth? By holding onto and accepting a relative truth in a way which transcends its application and value. When we hold onto some relative notion as an absolute, we turn a relative truth into a falsehood because we detach it from its integral unity with the truth itself. For this reason, after accepting that we can speak of God and speak truthfully so long as we recognize we do so in a relative fashion, Dionysius wrote the Mystical Theology to make sure we do not apprehend the relative truth as absolute truth and cut ourselves from the absolute truth itself. We are called to clear our minds of all such relative presentations of the truth, silencing our thoughts, indeed, silencing ourselves, so that we can encounter the truth itself in the midst of that silence. The Mystical Theology trains us to do this in two ways. First, it explains how and why we must deny our thoughts, our relative truths, through apophatic denials, thereby clearing our mind of all preconceived notions which we would otherwise hold onto and use as a lens for our engagement with the truth. Then it teaches us to transcend such apophaticism by telling us to no longer try to think and conceive of expressions of the truth: we are called to transcend mere apophatic denials so as to encounter the truth in the silence beyond all word and thought, not allowing anything in ourselves to interfere with the truth which is revealed to us when we encounter it.

Apophaticism is important, but it can be problematic. We must realize that our denials do not assert the truth, but only open up the way for the truth to be revealed. By denying what we consider to be false, we do not establish what is true: if we think so, we begin to assert something as the absolute truth which is not. We must free our minds, free ourselves from trying to assert the truth. This will make sure that our assertions do not become something which prevents us from achieving our aim of union with the truth itself. For, as Dionysius argued in his sixth letter, we can be right in denying the errors of others without being right in our own presentation of the truth:

Do not imagine this a victory, holy Sopatros, to have denounced a devotion, or an opinion, which apparently is not good. For neither—-even if you should have convicted it accurately—-are the (teachings) of Sopatros consequently good. For it is possible, both that you and others, whilst occupied in many things that are false and apparent, should overlook the true, which is One and hidden. For neither, if anything is not red, is it therefore white, nor if something is not a horse, is it necessarily a man. But thus will you do, if you follow my advice, you will cease indeed to speak against others, but will so speak on behalf of truth, that every thing said is altogether unquestionable.[1]

Often, our denials of what others say about the truth do not properly represent what apophatic theology is about, because our denials come not from some attempt to engage the absolute truth but rather out of comparison from our own views and opinions and how they differ from those of someone else. We deny what we do not agree with, thinking we have presented an apophatic denial, using it to claim that our opinion, which has not been denied, must be the truth. But, as Dionysius indicated to Sopatros, the truth transcends such a framework, and so is not found by making denials of this kind. We can be occupied in false categorizations, thinking something is either black or white, when it is neither (it could be red, blue, purple, green, yellow, orange, pink, or some other odd color). When we try to debate others, we come at them with a similar false apprehension of the truth, and so, likewise, we end up positing an equally false vision of the truth. We might be right in our denial of what someone else suggested, but this does not make our opinion, our speculation or assumption about the truth, to be true. We overlook the truth due to our conceptual and ideological attachments: the key to attaining the truth is to realize it is not going to be found in debating others, but in overcoming our own false assumptions and denying what we use to hinder our reception of the truth. For, as Dionysius explained in the second chapter of the Mystical Theology: God, because he is is above every abstraction and definition, is above the privationsm, that is, above all the categories which we would use to make affirmations or denials about him. The absolute truth is above human thought, and therefore, above all the categories and definitions which we use to describe it. This is why we deny relative presentations of the truth as being the absolute truth; but it must also be clear, such denial must not be a nihilistic denial. Such denial is about denying our mind and the concepts it uses to clothe the absolute truth for us to apprehend it. We must move beyond thought; while denials helps us transcend simple, erroneous conceptions of God, so long as we think along the lines of denials, we are still thinking about God, still attached to the realm of thought, and so we must deny the denials by silence all thought so that we can lifted up into a mystical state whereupon the truth can reveal itself to us, as Dionysius indicated at the end of the first chapter of the Mystical Theology: For by the resistless and absolute ecstasy in all purity, from thyself and all, thou wilt be carried on high, to the superessential ray of the Divine darkness, when thou hast cast away all, and become free from all.

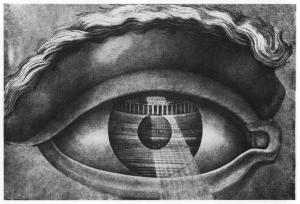

[IMG= Interior of the municipal theatre of Besançon (built by Ledoux in 1784), seen in the mirror of an eye by Claude Nicolas Ledoux [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Dionysius, “Letter Six” in The Works of Dionysius the Areopigate. Trans. James Parker (London: James Parker and Co,, 1897), 145.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook