Paul, in the letter to the Philippians, tells Christians that they are not to be lazy, that they are not to be sluggish, but rather, they must work out their salvation:

Therefore, my beloved, as you have always obeyed, so now, not only as in my presence but much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling; for God is at work in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure (Philip. 2:12-13 RSV).

God is at work in us, with us, and through us. We are expected to work in the world, to be workers not of iniquity but justice. “What man is there who desires life, and covets many days, that he may enjoy good? Keep your tongue from evil, and your lips from speaking deceit. Depart from evil, and do good; seek peace, and pursue it” (Ps. 34:12-14 RSV). We do this, of course, through grace: God works in our soul, molding us, shaping us, but we are expected to work with God, to cooperate with that grace by what we do. He does not force us to act, but he expects us to act. We, who have been given grace, we who have found our injustices healed by God’s charitable grace, are expected to act on that grace, to be doers of justice in the world. We are to be holy (cf. Matt. 5:4), lest we suffer a greater harm by ignoring God’s grace in us by acting unjustly.

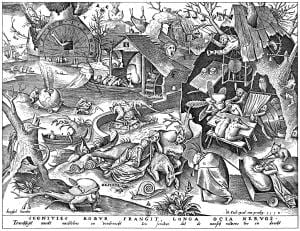

It is important for us to remember that if we are to be saved, we are to be just and good: we cannot ignore God’s justice, God’s expectations for us, and think we will continue to receive his blessings. “He who is steadfast in righteousness will live, but he who pursues evil will die” (Prov. 11:19 RSV). Salvation is through God’s grace, but it is also something which we engage in ourselves as we allow ourselves to be transformed from mere hearers of the word to doers of the word. We are to follow the example of Christ, bringing salvation to the world. That means, we are to work for what is just and true, fighting against and overturning all that is unjust. The temptation to leave it all to God, to think we should do nothing, is what the sin of sloth is all about: it is not mere laziness, it is about spiritual laziness, where we think we have nothing to do but sit around to receive God’s blessings and be all he wants us to be. Such selfishness ignores God: if we are hearers of the word, and we believe what he tells us, how can we sit about and do nothing when he has told us otherwise? If we follow the God of love, we will love. Love is not selfish. It is rather self-giving, seeking out the well-being of the beloved. One who cooperates with grace will cooperate with love, indeed, they will put off all objections to doing what is good and just and will do it with as much enthusiasm and zeal as they can muster: “Let love be genuine; hate what is evil, hold fast to what is good; love one another with brotherly affection; outdo one another in showing honor. Never flag in zeal, be aglow with the Spirit, serve the Lord” (Rom. 12:9-11 RSV).

Sloth, because it tells us that we do not have to do anything for our salvation, is a great and deadly sin; it turns us away from what is good and just, telling us that we do not need to do anything to achieve perfect justice. Salvation is tied to justice. We will not be among the saved so long as we remain in injustice. Sloth, in its lies, threatens our salvation. It will destroy us from within. “Through sloth the roof sinks in, and through indolence the house leaks” (Eccles. 10:18 RSV).’

The sin of sloth must not be confused with mere laziness, but rather, the unwillingness to do what is good and just: it is about the lack of cooperation with God and his grace. We are to continue Jesus’ work in the world. Sloth, on the other hand, tells us to abandon that work, to do whatever we want for ourselves, thinking we do not need to do anything for our salvation because it is all in God’s hands. The slothful often think they are wise, as they think they have one over God: God will save them without them having to do anything, but such wisdom is false, and so long as they are wise in their own eyes, they will not heed the word of God.

Connected to sloth, and sometimes seen as the same defect, is the problem of accidie, the listlessness which comes upon us, threatens to stop us in our tracks. It is often called the “noon-day demon,” that state or passion which comes upon us during the day when we begin to feel fatigued: will we fight against it, or will we let it drag us under and turn us away from the good which we should be doing? Often, when we feel fatigued, if we move about and act, we find it goes away; the same is with spiritual fatigue, accidie: when we ignore it and push on, we will find our strength returns, and we then we will be able to do what is expected of us for our salvation.[1]

It is important to keep in mind what Amma Theodora said: once we begin to pursue spiritual work, seeking out those acts of justice which are ours to engage, we will find ourselves being tempted by accidie: all kinds of thoughts will come to us, suggesting we have reached our limit. If we struggle against it, we will find those thoughts will go away as our vitality shows itself once again:

However, you should realize that as soon as you intend to live in peace, at once evil comes and weighs down your soul through accidie, faintheartedness, and evil thoughts. It also attacks your body through sickness, debility, weakening of the knees, and all the members. It dissipates the strength of soul and body, so that one believes one is ill and no longer able to pray. But if we are vigilant, all these temptations fall away.[2]

Nonetheless, we must also remember, not everyone has the same ability, the same strength and endurance; sloth is a problem of the will. If we are truly tired, if we are sick and with little strength, we should not berate ourselves, thinking we are worthless and so turn away from the grace which God offers us. Grace perfects nature, and so when we are weak, we can and should lean on God’s strength, not turning ourselves away from him by feelings on inadequateness, as Tauler wisely explained:

Sometimes good, pure-hearted people may be sluggish and apathetic without wanting to be. Their nature demands more sleep than they like to admit, but this is no reason for abstaining from Holy Communion. It is different with those seeking nothing but their own gratification: If they do not experience emotional comfort, a sense of security, and a warm glow, they stay away from the sacrament entirely. [3]

Zeal for salvation must be tied with a zeal for righteousness. Likewise, we must learn to encounter the goodness and beauty of the world in a way which does not make us spiritually lazy. It is easy to enjoy the goodness of God’s creation, ignoring the horrors and injustices around us, and if we do so, we will find those treasures will be taken away by the evils which take over due to our sloth. On the other hand, when we begin to see such injustices, when we begin to act, we must allow ourselves enjoy the beauty of the world, to be refreshed by it, to see the good in it, so that we see God made it of value and it is something worthy to fight for. One of the ways sloth takes root in the soul of someone seeking what is good and true is by making them denigrate the goodness of creation, so that, as St. Diadochos of Photiki said, we become listless, taking no pleasure in anything which is good:

When our soul begins to lose its appetite for earthly beauties, a spirit of listlessness is apt to steal into it. This prevents us from taking pleasure in study and teaching, and from feeling any strong desire for the blessings prepared for us in the life to come; it also leads us to disparage this transient life excessively, as not possessing anything of value. [4]

Thus, it is often a gnostic rejection of the earth, the goodness of creation itself, which turns us into slothful Christians. We lose care for the world, and so we lose care for justice. We know no peace or joy because we turn away from it. This is not what God intended for us or for the world. It was created good, and it is good, and it is full of goodness which can and should help find us relief when we need it, but it is also a good which we are meant to work with and preserve as stewards of the earth. To neglect the earth and its good is to reject the goodness of God and to fight against him and his justice, and so is itself a form of sloth.

“Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God” (Heb. 13:16 RSV). Our grace is given to us to transform us, to turn us into workers of God’s justice in the world. We share what we have been given when we work for others. The more we give of ourselves, the more we will grow in grace; if we take what we have been given, and try to hold it as for ourselves alone, we will find it will be lost to us (cf. Matt. 25:14-30). Sloth tells us to keep our gift hidden, to do nothing and enjoy the little that we have, but in doing so, we will lose it; so long as we work with it and share it with others, as long as we love others and seek justice in that love, we will find ourselves growing in justice and grace ourselves, until at last we have worked out our salvation and find that in the work we have already experienced the kingdom of God. “And let us not grow weary in well-doing, for in due season we shall reap, if we do not lose heart. So then, as we have opportunity, let us do good to all men, and especially to those who are of the household of faith” (Gal. 6:9 -10 RSV).

[1] This is not to say there will be no times of rest. We certainly need rest so as to regain our strength. The problem with accidie and spiritual fatigue is that it tempts us to stop short, to rest more than we truly need, to bring us into a spiritual stupor.

[2] Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Trans. Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984), 83 [from saying 3 of Theodora].

[3] Johannes Tauler, “Sermon 33” in Johannes Tauler: Sermons. Trans. Maria Shrady (New York: Paulist Press, 1985), 113.

[4] St. Diadochos of Photiki, “On Spiritual Knowledge,” The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume One. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al. (London: Faber and Faber, 1983), 270.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook