Several theological and philosophical paradoxes emerge as we try to deal with and contemplate the transcendental God within the limits of the human intellect and the thoughts and words it produces to theorize about God. As we reach out towards that transcendence, and realize truths which are revealed from it, we will find it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to coordinate all those truths into a consistent system. We must recognize and accept this from the onset. We can try to sort out paradoxes, suggesting ways to engage them; most often, we do this by favoring one side of the paradox over another as a hermeneutical tool, providing for substantial and helpful analysis. Nonetheless, because we have collapsed the paradox in favor of one side, we will find ourselves far away from the absolute truth itself. This should not upset us. We should humbly accept the limits of our abilities. We should always realize that what we produce will always be a human construct, and so it will be a derivative representation of the truth which falters because of the human conventions which we use to discuss the truth.

Several theological and philosophical paradoxes emerge as we try to deal with and contemplate the transcendental God within the limits of the human intellect and the thoughts and words it produces to theorize about God. As we reach out towards that transcendence, and realize truths which are revealed from it, we will find it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to coordinate all those truths into a consistent system. We must recognize and accept this from the onset. We can try to sort out paradoxes, suggesting ways to engage them; most often, we do this by favoring one side of the paradox over another as a hermeneutical tool, providing for substantial and helpful analysis. Nonetheless, because we have collapsed the paradox in favor of one side, we will find ourselves far away from the absolute truth itself. This should not upset us. We should humbly accept the limits of our abilities. We should always realize that what we produce will always be a human construct, and so it will be a derivative representation of the truth which falters because of the human conventions which we use to discuss the truth.

This is not to say we should end up nihilists, thinking there is no truth in what we have to say. We can know, for example, when our words are utterly false, such as if we claim to see a three-horned unicorn. For this reason, we can see the distinction between falsehood and the inadequacy of words to express the ultimate truth. So long as we recognize the limits of our conventions and do not absolutize them, we can discuss the truth; to do this, of course, we must let our words serve as pointers to the transcendent, absolute truth instead of trying to rely upon them to be univocal with that absolute truth. That is to say, we should recognize two types of engagement with truth: the conventional truth which we express in words, which is a relative truth, and the absolute truth which generates and establishes the veracity of the conventional truths so long as those conventional truths engage and participate in that greater transcendent truth. When what we suggest does not participate in the ultimate truth, then what we say can be dismissed as false.

This can be seen in many ways we talk about God, for example, in the way we relate God with creation.

We recognize that God, as God, is absolutely free in his will: he is free to do as he wills, and there is no necessity involved with his will. With that will, he established creation. Creation is a contingent, not a necessary, reality: it does not exist in itself. Its existence is a gift from God. This contingency reinforces the notion of God’s freedom. By showing it is contingent, we know it does not have to exist. It exists only because God wills it to exist. Only if the existence of creation were necessary and not contingent could it be shown that it was necessary for God to establish it. But then, for it to be necessary, it would have no beginning, nor no potential end; it would exist without any possibility of not-existing.

On the other hand, God is himself eternal. Indeed, in a way, God kataphatically can be declared to be a “necessary being.” If he is necessary, does that not make his actions, which could be shown to be eternal and unchanging as well, necessary? How, then, can God be said to create freely when he is himself a necessary being who acts in one eternal, unchanging act?

Possibly what lies behind this paradox is the fact that we do not truly know what it means to be eternal and to will in that eternity. We think about the will in relation to our own temporal context. We understand freedom, likewise, in a limited fashion, for while we have some level of freedom in our actions, we find our choices limited by temporal-spatial accidents. We are abstracting from our own particular context, and in that abstraction, we create our problem. We do not understand how freedom is observed in eternity because we do not yet live in and experience eternity (it is possible some mystics have experienced it in part, and so will have a better way of grasping how freedom is experienced in eternity and can help us out if we study them; nonetheless, what they say on this will only give us a limited, though better, grasp of the problem). Thus, when we think about willing, we include with it the possibility of changing our will due to ever-changing conditions, while for something eternal, there is a sense in which nothing changes, that is, no conditions change, and so there is no reason for that will to change. It is free, however, because there is no external imposition on it. There is no external force imposing upon God the necessity to create; likewise, the contingent nature of creation means God did not have to will creation to exist as there is no necessary reason for creation to exist. This is why it is said to be gratuitous. God, of course, has his reason for his choice, and we can say, through the aid of revelation, that love lies at the foundation of that choice, but we must in the end accept that even with such love, God could have chosen to act otherwise and did not. Creation is established by God in his eternal unchanging will, and in that creation, he established a different mode of being (temporality) which for God is with him in all eternity because of his free unchanging choice to establish creation but which for creation itself has a beginning and an end, being bound in and with time.

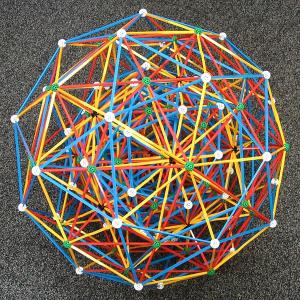

God transcends us. God transcends our ability to comprehend him. We are able to grasp after him, giving us in return some revelation from him about himself which we can engage in our minds. Each such revelation is like a piece of a puzzle. We can take them together and try to discern the full picture. This is what systematic theology tries to do. But there is a problem. It is not a simple puzzle. Rather, it is as if we are trying to reconstruct an eight-dimensional puzzle which has been down into two-dimensional pieces. We are trying to establish that picture in two dimensions because that alone is what we can comprehend. With an eight-dimensional puzzle being put down into two dimensions, we will find pieces which do not seem to fit; we will find pieces which all seem to belong at the same spot, overlapping and conflicting with each other as no two piece should hold the exact same physical space; and we will find the picture which emerges highly confusing as it truncates a reality which cannot be properly represented in only two dimensions. Our positive theological discussions about God are our attempts to take an infinite transcendence and express it in a limited form, indeed, in a form infinitely more confining to that transcendence than an eight-dimensional puzzle being squashed down into two dimensions. We will find and express truths which will not seem to fit together, which will seem to pound each other and contradict each other as they “fit” in the “same” mental space. This might not satisfy those who want succinct, logical solutions to theological dilemmas, but all they need to do is employ logic to see the limits of the human mind and understand what transcends human logic will always have this problem. This is not to deny the value of positive theology and attempts to do systematic theology: it is important, and it is important for logical arguments to be made to justify various theological truths, but it is also important we do so without then overextending what such logic is capable of doing and trying to construct an image of God through reason alone because if we do so, we will create an idol which halts our progression to God himself.

.

[IMG=This is a Zome model of the E(8) root system by Davidarichter [Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0] via Wikipedia]

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook