Étienne Tempier, in his famous condemnations of 1277, denounced the notion that God could not have made many different worlds other than our own. According to the logic of some, it made sense that there was one God, and that one God would make only one world. And yet, those like Tempier believed such assertion said too much, that it ended up limiting God, making him follow what seems as logically necessary from a limited human perspective. One great theological error, found throughout history, comes from the attempt to impose the human intellect upon God, to make God himself subject to the necessities that the human mind imputes about him.. Often, what existed, or what appeared to exist, seemed to become more than fitting, but said to be necessary, so that what did not exist, or what did not seem to exist, seemed to be impossible. Tempier, seeing such a reductionist epistemology coming from many in the scholastic movement wrote, therefore, to overcome their limited imagination, reminding them that God transcends their thoughts and ideas and he could do many things which we do not know he did, or many things which he decided not to do.

Étienne Tempier was not the first to discern such an imposition upon God. Several centuries earlier. St. Basil the Great also saw and heard many philosophers and Christians asserting there could be only one world. Basil thought the arguments which were made could be shown to be patently absurd through the example of how bubbles could be made:

For, there are among them men who say that there are infinite heavens and world; and, when those who employ more weighty proofs will have exposed their absurdity and will prove by the laws of geometry that nature does not support the fact that another heaven besides the one has been made, then we shall only laugh the more at their geometrical and artificial nonsense. For, although they see bubbles, not only one but many, produced by the same cause, yet they doubt as to whether the creative power is capable of bringing a greater number of heavens into existence. Whenever we look at the transcending power of God, we consider from that of the curved spray which spurts up in the fountains. And so, their explanation of the impossibility is laughable. [1]

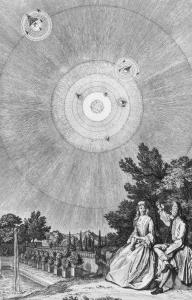

To be sure, not all of the debate concerning the plurality of worlds came out of a lack of imagination and an inability to conceive of a universe different from what existed. Rather, much of the debate was based upon equivocation. That is, people were arguing for different things when they wrote on the question of whether or not God could have made, or actually made, multiple worlds. For some, the whole of everything that exists can be said to be one, and therefore there could be no plurality of worlds, for whatever existed in that plurality would still be united together and seen as one, that is, one world. But what exists within that single unity could be and would be what others consider to be involved when discussing the plurality of worlds: that is, some of those saying there is but one world could still believe in a vast creation, with many localities far away from the earth they lived on. Others would think of the meaning in a way which we are now more familiar with, and so would say there could be a plurality of worlds, or actually is, along the lines of there being multiple planets in which life, including intelligent life, could be found. Of course, not all the disputes on the question of the plurality of worlds could be and would be based upon differing notions of what it means to say “world,” and some truly disputed any notion of God creating, or being able to create, planets other than our own. And it is to these that we can apply the criticism of Tempier and Basil and show that such answers must be rejected as limiting God. Whether or not such worlds exist, they could exist, and if they exist, that existence would come from God like all other things, for God is the one who brings to potentialities into actuality by granting them participation in existence itself. After Tempier, the question of plurality of worlds continued, with many, like Nicholas of Cusa, having no problem believing such worlds were not only possible but actually existed.

The debate over the plurality of worlds, a debate which goes back to pre-Christian times, and a debate which finds Christians on both sides of the debate, is but one example among many where Christians have had to learn how to think new thoughts and to use their imagination to consider what is possible without actually asserting what is actual. Time and time again, humans have had to question what they thought was impossible in order to let go of their false view of the world and to emerge with a greater insight into what was possible. Many modern inventions exist because ideological necessities were questioned and were proven false (cars, television, computers, and space craft can all serve examples of this). We become too accustomed to what is, and what we experience as things are, we begin to try to reason it so that our experience is necessarily how things are, and this true not just in religious discussions and debates, but in the history of empirical science as well. We try to normalize our experiences in this fashion.

It is for this reason I am hesitant in denying the possibility of artificial intelligence. It can be seen as an alternative take to the question of the plurality of worlds, for now it is the question of a plurality of forms of intelligent consciousness or life being generated, and generated in and through a variety of means. And, if we were to apply Tempier’s line of thought, we must at least say that just as God has the power and ability to produce a plurality of worlds, God could have made creation in such a way that intelligent consciousnesses can be generated by and made through the influence of other intelligent creatures of his. This should not be a problem with Christian theology, because historically, Christians thought life was generated in a variety of ways, including abiogenesis or spontaneous generation, and so it would actually fulfil the expectations of ancient metaphysics, though in a way the ancients could not have understood possible. Moreover, there could be an intuitive grasp of this notion seen in many works of natural philosophy used by so-called occult sources, where humans, imitating the creator, could be seen as sub-creators, generating life of their own (however troubling and dangerous such an activity would be); is this not one of the ideas seen associated with the production of the Golem in Jewish lore (or the legends of St. Albert the Great producing an automaton which St. Thomas Aquinas destroyed)?

It might seem that artificial intelligence is impossible because we have yet to produce it, or know how it could be produced; and yet there is much theory which suggests it is possible, theory which also thinks the way it will be produced will be similar to the way human consciousness evolved, but instead of evolving through the DNA which codes biological life, it would evolve in and through evolution of computer code. Metaphysically, there are many ways in which this possibility could even be examined as there are many metaphysical theories which exist to explain the relationship between the rational soul and body. What is known, however, is that something in the physical world, with a physical body, can somehow become conscious. Whether or not one argues the consciousness is spiritual, as I would, or merely an aspect of the way physical matter works, the reality would still be the same. There is some relationship between physical being and consciousness, and the physical being of the human mind, slowly being mapped out and imitated in and through computers, has the potential of producing a consciousness of its own. Obviously, we might not know if we have produced an artificial consciousness, because many could say all we experience is an imitation of consciousness instead of actual consciousness, but the way such questions would be raised could and should lead us to doubt the consciousness of others as well.

What Tempier tells us, and what is important for us today, is that we must not try to establish a closed system which tries to dictate what is possible based upon our limited understanding of the world; what we need is an open-ended system which encourages human imagination to consider what is possible. We need thinkers like Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov, Teilhard de Chardin, and others like them, who offer creative philosophical and theological ideas, who, even if they get things wrong, push us forward, outside of the ideological constraints which limits our ability to appreciate God and his creation. We need science fiction writers to speculate and think, not only what is possible, but the ramifications of those possibilities, so that if and when we realize them, we are prepared for them. We need people ready to consider many potential scenarios, so that even if they are not realized, by keeping ourselves open to what is possible, we really begin to see and grasp the greatness of being and all its true potentiality. And when we do that, then we can at last begin to approach God, no longer trying to limit him to the necessities we would impose upon him, and so truly marvel in his greatness as we recognize the potentialities which he established in the creation of being itself. Through his work, through his creative action, through what he has established not just in actuality but in potentiality, we truly get closer to God and apprehend better the great mystery which lies before us when we encounter him “face to face.”

[1] St. Basil the Great, “Hexaemeron” in Saint Basil: Exegetic Homilies. Trans. Agnes Clare Way, CDP (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1963), 40.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you have liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!