Being a famous scholar or theologian, offering invaluable works that help promote and develop Christian theology, does not make someone free from error. Many great theologians have ended up being schismatic, if not outright heretical. Despite what personal failures which might leady some scholars and theologians to eventually hold erroneous if not outright dangerous views, their works often remain invaluable to the Christian faith, so that Christians can and should learn from them, though with care so as not to take on whatever error which diverted them from orthodoxy.

History can give us many examples.

Though not the first, Tertullian (160-220) is a prime instance of this. We can study and engage his many works, such as but not limited to his Apology, Against Praxeas, On the Resurrection of the Flesh, To the Martyrs, and On Prayer, knowing of course, that he became a Montanist who took on extreme positions that ended up criticizing and rejecting various pastoral aspects of the Catholic faith. St. Cyprian of Carthage could take on Tertullian as a theological mentor while abstracting from his works all the crazy errors which Tertullian accepted as a Montanist. The greatness of Tertullian’s writings, recognizable by even his critics, makes them required reading. But reading him, learning from him, does not mean we need to follow him as he strayed from orthopraxy and orthodoxy: just because he was an important writer who helped shape the Latin theological tradition and give much of its vocabulary does not make what he said in all instances correct.

Novatian (200 -258), likewise was considered a significant Latin theologian. His On the Trinity is recognized as an important contribution to Latin Trinitarian theology, even if there were elements in it which suggested an erroneous subordinationism. His legalistic attitude towards the lapsed caused his schism with the Pope of Rome. He rejected the church’s pastoral authority to show mercy to the lapsed, saying they could not have their sins forgiven; in doing so, he demonstrated that just because he was an intelligent theologian, not everything he had to say was worthy of respect.

Apollinaris of Laodicea (d. 382) was a friend of St. Athanasius, indeed, an early defender of Nicea against the Arians. He properly understood the divinity of Christ, and helped the Nicenes in their contest against the Arians. Yet, he did not properly understand the incarnation, and so he suggested a less-than-human Christ as he denied a human soul to Christ. As a result, he was condemned as a heretic. He was a prolific writer, an influencer of many major Christian theologians and saints, and yet he took to his own ideas over and above any criticism which he received, demonstrating that even those who seek to protect orthodoxy and offer significant aid to orthodox positions can, in their hubris, go beyond the bounds of orthodoxy and fall into error.

Patriarch Nestorius (386-451) was a great student of Theodore of Mopsuestia, an eloquent, indeed, influential preacher. He held a prominent position in the church as the Patriarch of Constantinople. And yet, his pride got the best of him; he went against St Pulcheria, thinking he could use his position of authority to deride her and her feminine nature, only to find St. Pulcheria respond back to him saying his disrespect to her disrespected all women including Mary the Theotokos, the Mother of God. In his anger, he rejected Mary as being the Mother of God (even if he would later accept a nuance understanding of the term, Theotokos), and so, despite a prominence which led him to a major seat of ecclesial authority, he turned away from orthodoxy and those who followed him found themselves standing against the basic teachings of the Christian faith.

Example after example from history can be lifted from history, showing great theologian after great theologian, such as Peter Abelard, Martin Luther or Ignaz von Döllinger, straying as a result of overconfidence in their private theological opinions. Great theologians, great scholars, great intellectual or ecclesiastical leaders who had been properly raised in prominence for their work and achievements, can be seen letting their own accolades get the best of them, so that they ended up ignoring and rejecting some basic element of Christian doctrine or practice. Many of them, but not all, found themselves following an extreme legalistic interpretation of Christian practice, incapable of understanding the nuance which the Christian mystery demanded of any theologian. Instead of listening to the church, they though themselves above the church, indeed, they ended up thinking they could judge of the church and its leaders. They used whatever authority they had to lead many followers astray. Great heretics did not become great heretics because they were unlearned; they became heretics because they failed to grasp how the Christian faith was to be addressed despite their learning.

It is no different today. We can find many great scholars, many great theologians who once contributed something significant to the church’s theological tradition ending up subverting the church’s teaching in some particular manner and in doing so lead people astray. Their fame, their reputation, the value of their previous works are often used to suggest they cannot be in error, but that, of course, is a fallacious argument. It would, likewise, be a fallacious argument to suggest some particular, indeed, major error found in their writings means that all their work should therefore be ignored or rejected. One error falls under the domain of argument from authority, the other as a proper form of ad hominem; instead, what they have to offer, what they offered in the past, stands on its own merits, and when it is good, it can still be used as an invaluable resource despite whatever errors they have made elsewhere.

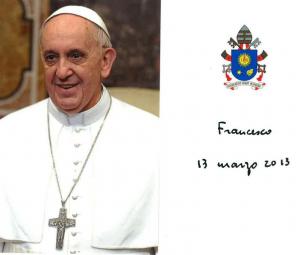

It is in this light that Catholics need to understand that no matter how prominent particular scholars or theologian are, their criticism of the Pope does not, indeed, cannot stand on the fact that they are prominent scholars. Their accusations of heresy, when examined, are risible. They demonstrate the same fundamental mistakes of Novatian, with a lack of understanding orthopraxis in connection to the pastoral needs of the people. Detraction, especially against the Pope, can be easily done by a warped, fundamentalist approach to the Christian faith. Any Pope, any theologian, any saint, any Doctor of the Church, can have text ripped apart and taken out of context to make them represent something contrary to the spirit and teaching of the faith: those who seek heresy will find something they can use to claim heresy. However, heresy is something which is judged by the church, and it is only when the church’s declarations are denied that proper heresy is found, for then it becomes a willed contention against the church’s authentic teaching authority.

Pope Francis is not in open heresy: only those who deny mercy, those who deny pastoral economy like Novatian can begin to suggest such. He promotes orthopraxis, the spirit of love and mercy and social justice, which is exactly the spirit which fundamentalists hate because it does not hold well to their simplistic, indeed, literalistic approach to theology. People who want simple answers, people who want judgment without mercy, legalism without grace, doctrine without mystery, can easily make themselves appear to follow tradition through the words they use. Nonetheless, by the spirit of their words, it can become clear how far they are from the truth. They end up limiting God, limiting the faith, thinking that their simple understanding is the extant of the truth itself: this, of course, is what is being challenged by Pope Francis, and why he finds many of them contending against him.

Yes, there are some great theologians, like Aidan Nichols, who have contributed much in the theological disciplines, who seem to now stand against Pope Francis. They can be respected for and thanked for what they have contributed in the past. But their own limits to the Christian faith do not have to be followed just because of their scholarly background. The Christian faith is not a faith reduced to scholars and their ideologies. Authority is not had by mere study, but rather, by a charism which transcends study and the people who hold it. A great theologian can easily fall for their own greatness and think apart from the faith, to choose to hold to their own private theological ideas over and above the church’s teaching and practices; in doing so, they show why they do not have to be followed, for all they offer is a private opinion, an opinion which does not bind the church because of its private nature. Demanding what they do not have the authority to demand, proclaiming someone a heretic without the authority to proclaim heresy, will only undermine whatever contributions they could otherwise offer the church. Vladimir Solovyov once indicated that the Protestant faith was primarily a faith of scholars, where everyone can come up with their own opinion and view; it is this which Catholicism overcomes, not by denouncing scholarship, but by making sure scholars recognize the limits of their opinions. When we see scholars making demands, they go beyond the domain of scholarship, and therefore, beyond the domain of whatever authority they might have. They do not need to be listened to: indeed, when what they offer is ridiculous, they should not be listened to, but only ignored.[1]

[1] N.B., I recognize I did not “respond” to the letter itself. I do not have to do so. The ideas within them are sufficiently ridiculous they do not merit that kind of response. I rather wanted to deal with the way its writers and signers are treated with respect, as if we should heed them because of their previous theological contributions. If that is all it took to be accepted, then theologians from another end of the spectrum, like Hans Kung, Bernard Häring, and ,Charles Curran should be given the same credibility and deference.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you have liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!