Catholic Social Teaching cannot be dismissed as an optional part of the Catholic faith. It is not only a part of the deposit of faith, it represents a major part of it. Scripture presents social justice as an inherent part of the Gospel, even as it was a major part of the preparation of the Gospel with the people of Israel. Social justice is not some secondary extra to the faith: it is a part of the faith itself. There are some who would like to reduce the faith to various ideological concept, but Scripture is clear, faith without works is dead, for faith is not about the pursuit of knowledge but a life of holiness lived in and through the teachings of Christ.

There are many people who either ignore or reject Catholic Social Teaching. There are many reasons for why they do this. Many have not been taught its central role in the Christian faith, and so they do not take time to pursue it. Others, however, have ideological reasons. Catholic Social Teaching challenges worldly ideologies. Thus, for example, a common response against Catholic Social Teaching in regards its criticism of economic materialism, especially the forms currently holding power, such as capitalism, try to denounce Catholic Social Teaching as being unrealistic. That is, they claim that how things work in the world stands contrary to the demands of social justice. They think that how things work within the capitalistic system is how things work by nature. For this reason, Catholics who criticize the results of capitalism are said to be ignorant of economics, while in reality, those who reduce economics to one ideological system ignore the value and limitations of economics. Economic systems, like all systems, are constructs which can and do impose various results upon the world, but because they are ideological constructions, there are other systems which can be made, other systems which can lead to and produce different results. Those who want a system to engage in social justice can therefore establish such a system, and if it were put in place, it would then produce different results than the system which is currently in place.

It is clear that the so-called reality which many defenders of the grossest excesses of capitalism want to defend is “Social Darwinism.” They want a system in which the strong survive as the weak perish. This, they think, is the nature of things. It is a “dog eat dog world.” While there is truth that this is how things are, especially if there are no regulations put in place, the fact that there can be regulations which would change the system demonstrates that this is not how things must be. Justice will be concerned about the poor, the needy, the weak and powerless, to make sure that they can survive. Regulations can be made (and have been made) to help balance things out instead of letting power and wealth become slowly concentrated in those who already have them at the expense of those who do not.

Catholic Social Teaching, in its reliance on the commutative nature of justice, makes it clear, economics must be put to work for the common good. Society does not have to let things be so that the strong takes out the weak, letting only those who are seen as strong and powerful thrive. Society should work together for the common good: this is exactly what the good expects, to bring people together so that they can be stronger, better together. Sin, and the structures which develop around sin, goes against the common good as it promotes the private, individual good, no matter what happens to everyone else: sin divides, establishing a fragmentation of society, turning it into a group of individuals in conflict with each other. Capitalistic systems often rely upon this fragmentation, and therefore works against justice. It sees no reason to defend the poor and weak when it does nothing for the production and accumulation of capital.

Justice is social. Those who try to establish a system in which solidarity is neglected for the sake of individuals and their wants and desires irrespective of the needs and others undermine justice. Those who write for and promote capitalism by defending it against all criticism show why their responses will lead to the rejection of justice. When justice is undermined, capitalism will find itself short-lived. For the principles which capitalists use to justify its ideology, such as notions of possession, rely upon an application of justice upon a social sphere. Only so long as society as a whole agrees with the claims made by capitalists as to who possesses the goods of the earth can the system remain, but that requires a social idea, a social construct. Then, capitalism is bound to perish under its own weight: capitalism borrows from notions of social justice while denying them. Eventually, that denial will be accepted, and capitalists will have no justification they can give for the distribution of the goods of the earth. To complain about theft is to promote a system of justice; but when justice is undermined, how long will it be until theft is no longer seen to be immoral? Until the system implodes, capitalists will employ notions of justice because they are useful, not because they actually believe in them: capitalists will say it is just to defend their own earnings, but they will find every reason and excuse to take unjustly the earnings of others (such as when employers do not give living wages to their employees). The common complaint promoters of capitalism use against socialism plays against this self-contradiction, for capitalists want to suggest socialism is unjust while undermining the universal destination of the goods and the justice which the universal destination of goods demands. It is a rhetorical response which cannot and will not last: in the end, the self-contradiction employed to defend capitalism will collapse, just as all capitalist systems by themselves will collapse once wealth distribution becomes grossly unbalanced.

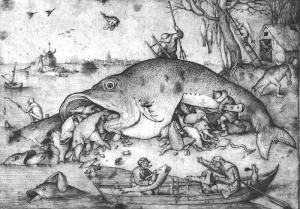

Indeed, though they think they have caught on to the truth as to how things work, and through it, can counter Catholic Social Teaching, critics of Catholic Social Teaching should be shown how their ideology had been noted by and criticized long before the advent of capitalism itself (capitalism, after all, is a modern system and must not be confused with free enterprise). Greed has long been a problem long; capitalism has found a way by which those who are greedy can better and more systematically generate wealth for themselves. The more someone who is avaricious cares less about the ramifications of their actions on others, the more they take in for themselves. But this is how greed has always worked. St. Basil the Great saw the way fish eat each other served as a fit analogy to the injustice which arises in a system which is based upon justifying the way the wealthy take from and destroy their inferiors: though it is true the bigger fish will eat the little fish, the biggest fish is no match for a fisherman and their hook:

The majority of fish eat one another, and the smaller among them are food for the larger. If it ever happens that the victor over the smaller becomes the prey of another, they are both carried into the stomach of the last. Now, what else do we men do in the oppression of our inferiors? How does he differ from the last fish, who with a greedy love of riches swallows up the weak in the folds of his insatiable avarice? That man held the possessions of the poor man; you, seizing him, made him a part of your abundance. You have clearly shown yourself more unjust than the unjust man and more grasping than the greedy man. Beware, lest the same end as that of the fish awaits you — somewhere a fishhook, or a snare, or a net. Surely, if we have committed many unjust deeds, we shall not scape the final retribution.[1]

A system based upon greed is a system based upon exploitation. When material wealth is the focus, instead of justice, obviously those who do not follow the system will suffer at the hands of those who do. This might seem to justify selfishness, indeed, to make selfishness appear as a virtue, because it appears to be what leads to security and happiness, but as St. Basil warned, there is no true security established in such a system. Someone will likely come who is stronger, craftier, who will take and consume what others have made for themselves. Money can be a useful tool when it is used to help distribute goods justly to all, but it becomes a tool for injustice as it is slowly taken out of circulation and becomes more and more the possession of a few.

What good, then, is there in the defense of a system which works in favor for the greedy? None! Moreover, though it might appear to be how things are, because it is based upon vice instead of virtue, it is far from natural. It might be the way things work under structures established by and dominated by sin, but as all sin is based upon delusion, so the system established in and through sin will be delusional, giving the appearance of the good while being anything but good. This is why it often appears to be natural, as all sin appears in some way, to be natural, as it borrows from what is natural but corrupts it, using an element of the to justify its own perversion of the good.

While what is demanded by justice can be difficult to discern, and to establish a system in which such justice is truly promoted will take time to put into effect, we must not allow arguments which suggest “that is the way things are” to promote that sloth which leads to perdition. St. Basil, once again, explained how this is what establishes evil in the world: “That evil is not a living and animated substance, but a condition of the soul which is opposed to virtue and which springs up in the slothful because of their falling away from the good.”[2] We might not, of course, produce utopia, but this does not mean we cannot and should not try to make things better and use prudence to promote what justice demands. This is what Catholic Social Teaching promotes. It is what Catholic Social Teaching expects of us.

[1] St. Basil the Great, “Hexaemeron” in Saint Basil: Exegetic Homilies. Trans. Agnes Clare Way, CDP (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1963), 109.

[2] St. Basil the Great, “Hexaemeron,” 28.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you have liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!