Christians have always been engaging themselves with the cultures in which they live. They have done this both transforming the culture from within, but also by allowing the culture to transform the way Christians represented themselves by addressing, and applying, the values and beliefs of the culture at large to the Christian faith. That is, Christians have let the culture they live in establish the symbols and standards in which Christians are to act and think. This is not to say Christians did this indiscriminately. Not everything they find in a given setting is acceptable, which is why Christianity is able to bring something new, something transcendent, as it “baptizes” the cultures it enters, but on the other hand, Christians have learned much of what they find is not only suitable, but capable of offering new insights which they can use as they practice their faith. Thus, by pointing out Christians engage the cultures of the world is to show that Christianity is able to express itself, indeed, demonstrate itself to others in a variety of forms. Its core teachings and values remain the same even if the way it promotes itself to others changes over time.

The earliest conflict on inculturation can be found in the conflict between the “Hellenists” and “Hebrews,” that is, between those who promoted that Christianity could and should engage and accept Greco-Roman practices and ideals, and those who thought all Christians had to transform themselves to follow a purely Jewish form of the Christian faith. Of course, those who were among the “Hebrews” failed to note that Judaism itself had a long history of inculturation and even those who were most adamant against Hellenization had been Hellenized to some extent.[1] Those who defended the Hellenists, therefore, were the most honest in regards the faith. There was no “pure” Judaism apart from Hellenism when Christianity emerged, and there was no need for there to be, because the Christian faith, coming from Judaism, incorporated and continued the most universalistic elements of Judaism. Canaanite, Egyptian, and Persian influences could be seen within the Tanakh, and with the translation of the Tanakh in Greek, and later writings being written in Greek, even by those who were hostile to Hellenization, shows the way God has always been at work within the Jewish, and then the Christian tradition, to adapt itself and take on the good which was found in the teachings and practices of others.

For Christians, the Council of Jerusalem provided the firm foundation for its ongoing Hellenistic inculturation (cf. Acts 15). It should not be surprising, then, when the church finally established itself on the side of the Hellenists (even if it was not on the side of the extreme Hellenists), its missionary activity not only increased but became so successful that more and more of the early Christian converts could be seen coming from a Gentile background.

With more Gentile converts, more Hellenization took over the church. This can be seen in the way the early Christians created images to represent their faith. The very fact that they found images permissible and were used in places such as the catacombs demonstrates an element of Hellenization (one which, to be sure, was found in Judaism and many ancient synagogues as well). They employed many simple images from Scripture, but also, they slowly adapted and used various Greco-Roman ideas, including myths, to represent Christ and the Christian faith. Thus, as Leonid Ouspensky explained, we find representations of Christ borrowing from and incorporating elements from legends surrounding Orpheus:

Another symbolic representation of Christ is borrowed from ancient mythology: the rather infrequent representation of Christ as Orpheus, with a lyre in His hand and surrounded by animals. This symbol is frequently found in the writings of Christian antiquity, starting with Clement of Alexandria. Just as Orpheus subdued the wild beasts with his lyre and charmed the mountains and trees, so did Christ attract men with His divine word and subdue the forces of nature.[2]

Early Christians could only go so far with the production of images. They could not adorn most of their dwellings with images that would attract attention, as they feared for their lives. Most of our archeological evidence of early Christian imagery comes, then, not only from the texts which we have from the ante-Nicene era, but places such as the catacombs, where they were the most free to express themselves in an artistic manner. When we see what remains, we learn how much of their art came out of Hellenistic ideals. It was what they knew, and they saw nothing wrong with such an adaptation of the faith. Thus, we find them expressing theological themes but doing so in a way in which they borrowed non-Christian mythological sources to do so. Early Christian art, early Christian adaptations to meet the needs of its Gentile converts, continued the universalization of the faith suggested by Jewish sources, but they did so in a greater fashion than their Jewish counterparts. And it was for this reason why, when Christian truly was welcome in Roman society, what was accepted as a practice in the past, became the means by which Christianity promoted itself in triumph after Constantine’s conversion.

It is important to realize the value of Constantine. He did not make Christians follow pagan ways; he did not corrupt the Christian faith by promoting Hellenization, rather, he acted as a catalyst to help promote and exponentially increase what was already being engaged by the Christian, or, as Ouspensky noted:

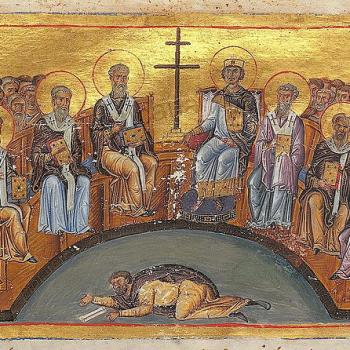

In the fourth century, under St Constantine, the church received the right to legitimate existence in the Roman Empire. This historical event, of capital importance, let to the triumph of the Church and had very important consequences for its art. Construction and adornment of the churches was developed to a point unknown until that time. [3]

But how were Christians to do this? They did so not only by following the examples of the past, they took a great interest in aesthetic theories and adapted Greco-Roman notions of portraiture in order to establish their own iconographic canon. Aesthetic theories of the third and fourth century, theories which were often Platonic in notion, were used to produce images. As the greatest representation of these come from the Greek or Byzantine side of the church, Gervase Mathew’s statement of Byzantine aesthetics is right on point: “The aesthetics of Plotinus provide the formulae which render all periods of Byzantine art intelligible.” [4] Plotinus established many ideals which were to be used for artistic representations, including and especially those which would be employed in the East with its iconography. Once Christians did not have to be in hiding, but rather, could build churches and adorn them with images to glorify God, they took what was the best representation of art from their age and used it to establish the norms used to produce images. Thus, its notions of color and light follow this basic Hellenistic (and Platonic) idea:

The characteristic Byzantine conception of the relation between colour and light, and the Byzantine delight in the colour of gold, are already explicit in the first Ennead. ‘All the loveliness of colour and the light of the sun.’ ‘And how comes told to be a beautiful thing? And lightning by night and stars, why are these so fair?’[5]

To be sure, it was not just Platonic insights which led to the way Christians portrayed themselves and the faith. They also borrowed from high society. Their painting followed examples made by funerary images,[6] as well as to the style of art established to reproduce images of the Emperor. Indeed, it is the second, which also borrowed from Hellenistic ideals, which can be seen as the foundation for Christian presentations of Christ as ruler of the universe:

The palace art of the fourth century exercised a decisive influence on the development of Christian iconography. It was the model for representations of Christ enthroned as a ruler of the universe, surrounded by angels and saints. As the emperor enthroned gave to the high officials of the empire the scroll containing their authorization, so Christ gave the new Law to Peter. [7]

Indeed, as Mathew points out, the relationship between the emperor and his image gave Christians an understanding of the way Christ and the saints can be seen to be present in Christian images:

It had long been held that there was a special relationship between the Emperor and his Image. Its presence signified his presence by proxy, any honour or insult paid to it was paid to him. By natural association such a conception could be transferred from official secular art to the art of the new and official religion. Increasingly Christ was shown in the apse to signify that He presided at the altar beneath Him. The presence of the angels and saints sharing in the liturgy was signified by their representation as they hovered above the altar or moved precessionally toward it. [8]

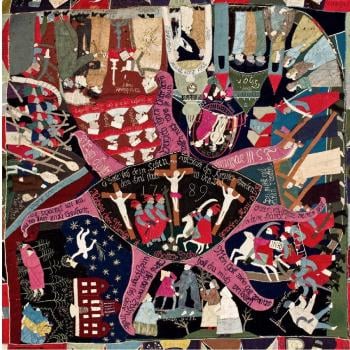

While such developments were going on in the church, there were many who were fighting against them, each and every step of the way. Tertullian is famous for his questioning of the relationship between Athens and Jerusalem, between Hellenization and the Christian faith, though his question was more rhetorical than an assertion, as he was himself Hellenized in his style and content, and in his livelihood as a lawyer. The rise of iconoclasm, which itself ignored the Hellenized tradition with the synagogue which used images in their buildings, can be seen as a major attempt to stop Christian engagement with the world, but its fight was a losing fight, as the ordinary Christian (and many of its leaders, especially women) fought for and defended the right of Christians to employ images in their worship and spiritual practices. Christians had come to accept that Christianity could and should address people in ways which they can understand the faith, adapting cultural norms in the process, indeed, learning from them if possible. Many unique elements of Irish Christianity come from its adaptation of pre-Christian Irish cultural norms. From the style of the Celtic Cross, to its more nature-based aesthetic and interest, Celtic Christianity was unique in its presentation and style. This is because Christianity was not a religion which required one form of worship, one way of being Christian, but rather, one which accepted different cultures could and would engage the faith and produce their own liturgical and iconographic heritages:

Worship can be celebrated in different languages and can take many forms. Similarly, a church can be shaped like a cross, a basilica or a rotunda. It can be built according to the tastes and the ideas of any epoch or of any civilization, but its meaning was, is, and will always be the same. Each people leaves its characteristic traits in the construction of churches. [9]

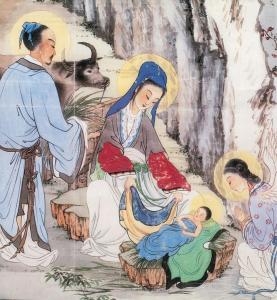

This can be seen in the way the greatest missionary activity of the early church, coming from the Syrian Church of the East, adapted itself and its presentation in China. Not only were various cultural images, such as the lotus, employed, but the way Christians presented themselves borrowed from sources the Chinese had grown to understand, such as Buddhism. It was only due to the fact that a rise of xenophobia in China that Christianity found its early missionary endeavor squashed. But even then, though it was greatly hindered, elements of that early success were preserved, showing how Christians were willing to engage China and its cultures in its earliest years so that when someone like Matteo Ricci started his own inculturation in China, it could be said he was engaging a very traditional approach to missions (even if he did not know much about the early Syrian missions).

While Christianity, from its foundation, was Hellenized, when Christians engaged missions in other parts of the world, they did not demand strict

adherence to Hellenized norms. Obviously, elements of such norms were employed, but they were adapted to meet the cultural sensibility of those whom the Christians were engaging. Modern missionaries have learned this lesson, and this is why many of them, especially the best of them, find themselves learning from and adapting themselves those they meet with, such as those missionaries working in the Amazon. Indeed, it is often seen that the first step of any modern mission is to meet people and just listen to them, hear their wants and desires, get to know their ways, and to interact with them and become one with them as friends and join in with them in their cultural ways. Then the Christian missionary, when asked about their faith, can present it in a way which meets the needs of the people they are with, addressing them on their own terms instead of first demanding they change their cultural norms before coming to and accepting the Christian faith (which was one of the many wrong things colonial missionaries did, causing much antagonism with the people they believed they had come to serve).

Christianity is an adaptable faith. The teachings remain the same. Its general moral expectations remain the same. But how those teachings and expectations are met change over time. In each new culture, in each new situation Christians find themselves in, if they want Christianity to survive, they realize it must adapt and accept new ways to imagine the faith. If and when it doesn’t, if Christians merely try to impose their own cultural legacy on others, they end up causing the resentment which leads to large-scale rejection of the faith. When Christianity cannot adapt itself to meet new situations, its spiritual well has dried up, and only when a new well is established can it continue to offer the spiritual drink people need. Those who fight against such adaptations always lose in the end, as the world continues to move on without them.

[1] See, for example, Martin Hengel’s classic work, Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in their Encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period.

[2] Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon. Volume One. Trans. Anthony Gythiel and Elizabeth Meyendorff (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1992), 69.

[3] Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon. Volume One, 20.

[4] Gervase Mathew, Byzantine Aesthetics (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1971), 19.

[5] Gervase Mathew, Byzantine Aesthetics, 19.

[6] “There is little doubt that Christians followed contemporary practice in having funerary portraits painted of distinguished church members. These portraits showed the busty of the person, facing forward, often enclosed within a medallion,” Hugh Wybrew, The Orthodox Liturgy (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003), 24.

[7] Hugh Wybrew, The Orthodox Liturgy, 31.

[8] Gervase Mathew, Byzantine Aesthetics, 96.

[9] Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon. Volume One, 21.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!