There is in the Eastern Christian spiritual tradition, especially in Russia, the notion of the passion bearer, the saint who was killed, not as a martyr for the faith, but for some other reason apart from the faith. And yet, because of their faith, they did not resist or their attacker with violence, demonstrating extraordinary virtue in their death. Because Christ willingly went to his death, decrying the use of violence when Peter tried to resist the Roman soldiers, the passion bearers are said to share with Christ a particularly holy, particularly important, glory which is rare among humanity. They renounced the evil of violence, even to the point of death. Indeed, most of them went further than this, and showed great love and compassion to those who assaulted them that they gave their forgiveness to their attackers. They chose a higher, more difficult path, and they chose it because they believed it was what Christ would have them do. For this reason, their deaths are honored, even though they were not martyrs who were killed because of the Christian faith. For in their deaths, they demonstrated their full desire to follow the precepts of Christ, to follow after him with self-emptying love; they humbly accepted their fate upon the earth. They found a way to make what could have been a worthless, terrible death, have great spiritual value.

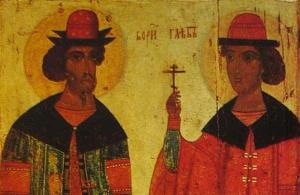

The most famous of the passion bearers are St. Boris and Gleb, two sons of St. Vladimir. They were killed because of the political ambitions of their brother, Sviatopolk (who may or may not have been Vladimir’s biological son). Sviatopolk’s pursuit for power begun while St. Vladimir was still alive. He tried to take it from his father. When Vladimir was confronted by his son, he had him imprisoned; when Vladimir died, Sviatopolk was freed, and soon seized power. Boris was away with the army when this happened, and Sviatopolk had him assassinated upon his return. Sviatopolk had his younger brother, Gleb, assassinated by his cook. Both Boris and Gleb, according to the accounts of their deaths, willingly died instead of fought back against their killers. They also knew it was their brother who orchestrated their deaths, but they had nothing but the desire that he would find mercy for his evil deeds.

St. Boris and Gleb were the first officially canonized saints of Rus. Although they died political deaths, the story of how they died established within the Rusian psyche the realization of the virtue of non-violence, a virtue which was capable of being demonstrated when someone found themselves confronted with a cruel death Thus, George Fedotov wrote:

Saints Boris and Gleb created in Russia a particular, though liturgically not well defined, order of “sufferers,’ the most paradoxical order of the Russian saints. In it are included some victims of political crimes the princes or simply victims of a violent death. Among them one finds many infants, the most famous, Prince Demetrius of Uglich in the sixteenth century, — in whom the idea of an innocent death is blinded with the idea of purity. In most cases it is difficult to speak of voluntary death; one is entitled to speak only of the nonresistance to death. Apparently, this nonresistance communicates the quality of voluntary sacrifice to death by violence and purifies the victim in those cases where, except for infants, the natural conditions of purity are lacking.[1]

While the hagiography surrounding Sts. Boris and Gleb indicates that they probably could have fought off their killers and possibly survived, not all passion bearers have such freedom. What is important is that all of them resisted the engagement of any violent forms of self-defense (no matter how successful they could have been). A passion bearer transcends human expectations. It is not that they are martyrs, but they follow the path of the martyrs because they follow the higher path which the martyrs chose: the difference is that the martyrs were specifically killed because of their faith in Christ, while the passion-bearers died for other reasons, and yet their faith in Christ shaped the way they reacted when faced with death.

There are many examples of such passion bearers throughout history. Saint Panteleimon, St. Edward the Martyr, and St. Doulas the Passion Bearer are often mentioned to be among this noble group of saints. St. Moses the Ethiopian, who likewise renounced violence and let himself be killed in his monastery when it was under attack by some Berbers, could be and should be described as a passion bearer as well. Similarly, St. Maria Goretti’s death is best be understood within this categorization of saints: that she died a holy death cannot be rejected, but if people were introduced to the category of the passion bearing saint, they would less likely misunderstand that holiness and try to impose upon others an ideology which runs contrary to the dignity of her death (the notion which is expressed in the way some think sexual assault victims are impure if they are not able to stop their attacker from sexually abusing them).

What is key for the passion bearers is the love of Christ; they share it to one and all, even to those who will them ill. Indeed, as the First Epistle of John indicates, those who take on the love of Christ to all cannot truly be killed: they have already passed on from death to life, while those who remain hateful and angry at the other remain consumed by death:

We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brethren. He who does not love abides in death. Any one who hates his brother is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life abiding in him. By this we know love, that he laid down his life for us; and we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren (1Jn. 3:14-16 RSV).

Likewise, the passion bearers can be said to live out the ramification of their baptism. Paul explains that all of us who are baptized have put on Christ, and so participate in his death and resurrection:

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. We know that our old self was crucified with him so that the sinful body might be destroyed, and we might no longer be enslaved to sin. For he who has died is freed from sin. But if we have died with Christ, we believe that we shall also live with him (Rom. 6:3-8 RSV).

The passion bearers participate in the death of Christ, not just spiritually, but physically; they can be said to be united with his death in a special way. The passion bearer lays down their earthly life while retaining what they have partaken of the kingdom of God. They do not look to violence as a response to violence: rather, they look to the example of Christ and follow him in forgiving all who would harm them. This is, to be sure, the higher path, the harder path, and many Christians are unable to attain this state of compassionate love. They know they are to love their enemy, to do good to those who would persecute them, but their earthly habits remain with them, and so they do not follow Christ’s precepts to spiritual perfection. What is extraordinary is what we see with the passion bearers. They show us, through their deaths, how they have truly have become partakers of the divine nature and experienced, at least in part, the kingdom of God in their lives, so that they could do what most of us cannot. They show us the true Christian response to others: it is not, of course, that Christians are to do nothing when facing evil in the world (they must engage social justice); rather, it shows that Christians must react with the dictates of love and justice, and when they have nothing else left they can do but love, then that is what they are called to do (but if, at other times, they have the ability to enact change, they should try do all that they can to do follow the dictates of justice).

When we understand the ramifications of the Christian life, we will note that so long as we live, we should strive for improving the world, making it a more just place, but we will also realize that we must accept that death will come to us. Not all of us will come face to face with some great evil when we die. But, it is true, some of us will, and if we do, we will be challenged. Will we embrace the opportunity and follow Christ in a death which demonstrates self-giving love to all, even to our oppressors, hoping that by such a witness we might transform their hearts and bring about a positive change in the world, or will we face them with the habits of death, taking their path and embracing it by violently resisting their violence, ratifying the path of violence and death in the process? Obviously, because of human frailty, most of us will likely follow the second path, but those who have been so touched by Christ, by the love of Christ, who do the first truly deserve our honor and respect. They have manifested the kingdom of God in and through their deaths.

[1] George P. Fedotov, The Russian Religious Mind (I): Kievan Christianity. The 10th to the 13th Centuries (Belmont, MA: Nordland Publishing Company, 1975), 104-5. [Volume Three in the Collected Works of George P. Fedotov].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!