The Sayings of the Desert Fathers often provides monastic wisdom which can and should be adapted and applied universally. Obviously, the foundation of that wisdom came from the developing monastic communities which had to learn how to live together. As those communities had needs which differed from secular communities, not all they taught needs to be followed by all. Nonetheless, the basic lessons they learned were universal and the insight the spiritual masters attained can be and should be heard by all. This is because they sought various practical applications to the Christian faith.

It’s easy to get caught into sophisticated theological disputes. It’s even easier to get caught in a faith which is reduced to an external show. The desert mothers and monks learned that the Christian faith was more than all of that. It had to be real. And to make it real, it had to be humble. When we start focusing on ourselves, trying to put our own wants and desires above all others, we lose humility, and so we lose our way. To overcome such an error, we should learn from Abba Motius that we must not make ourselves appear different from others so as to suggest some sort of superiority about ourselves; rather, we should learn how to live with and be like those around us:

A brother questioned Abba Motius, saying, ‘If I go to dwell somewhere, how do you want me to live?’ The old man said to him, ‘If you live somewhere, do not seek to be known for anything special; do not say, for example, I do not go to the synaxis; or perhaps, I do not eat at the agape. For these things make an empty reputation and later you will be troubled because of this. For men rush there where they find these practices.’ The brother said to him, ‘What shall I do, then?’ The old man said, ‘Wherever you live, follow the same manner of life as everyone else and if you see devout men, whom you trust doing something, do the same and you shall be at peace. For this is humility: to see yourself to be the same as the rest. When men see you do not go beyond the limits, they will consider you to be the same as everyone else and no-one will trouble you.’[1]

Pride gets us in trouble. We will never be what we appear to be when we try to glorify ourselves. We should not think we know better than everyone else. We should not force others to conform to our desires. Rather, we should find a way to be at peace with others, and that way is through humility. Such humility allows us to be aware of others, to learn from them, to make our peace with them and their ways by joining in with them and being like them.

This is a lesson the church has had to learn many times throughout the centuries. The best missionaries are not those who go around the world acting like colonizers, trying to make the world conform to their own particular ways. The best missionaries are those like St. Cyril and Methodius, those who try to enculturate the Gospel to the various cultures of the world. Trying to reduce the practice of the faith to one cultural form, to one liturgical form, to one way of Christian worship, will only hinder the full, effective spread of the Gospel. Christians must be willing to learn from those they encounter; to conform, insofar as they can, to the culture they find themselves living, and to see what within that culture is worthy of elevation and has something to share with the rest of the Christian faith. Or, as Motius suggests, we should follow the manner of life of those around us, learning from the best of the people in the culture at large.

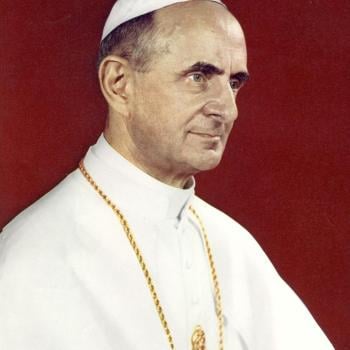

This wisdom is evident in Querida Amazonia. Pope Francis, coming from Latin America, has seen the results of colonization in the past, the harm it has done to the indigenous people, and the need for Christians to do better:

The important thing is to promote the Amazon region, but this does not imply colonizing it culturally but instead helping it to bring out the best of itself. That is in fact what education is meant to do: to cultivate without uprooting, to foster growth without weakening identity, to be supportive without being invasive. Just as there are potentialities in nature that could be lost forever, something similar could happen with cultures that have a message yet to be heard, but are now more than ever under threat.[2]

It might surprise some that the wisdom of the desert, the wisdom of an ancient monastic community, is the wisdom which is needed for evangelization. For it might seem the two are worlds apart. But the reality of monasticism is that it is about evangelization, of forming a particular community in which the Gospel can live and thrive, and in doing so, helping reshape a small corner of the world. Its lessons are universal. The community and the needs of the community might differ from place to place, from religious community to secular community, but the principles behind such community formation remains the same. The desert fathers and mothers passed on to subsequent generations what works best for living out the Christian faith. They had to learn how to make peace with each other. They found out, as Motius indicates, that they had to listen to each other, avoiding any attempts by any one person to take control of the community and form it under their own image.

“Do nothing from selfishness or conceit, but in humility count others better than yourselves” (Philip. 2:3 RSV). We must not think ourselves better than others. Likewise, we must not think our own culture is so superior to all others than all others should conform to it and its standards. We must practice cultural humility. We must accept that all cultures their own ways to approach the truth of the Gospel. Pride has caused all kinds of harm in the Amazon region, as it filled the land with the seeds of hate and destruction. Now, the church, passing on the faith in the Amazon, must not send people who trust in themselves and think themselves and their plans as betters than those they want to engage; rather, the church must have those who want to build peace in the region through inculturation if the church wants its work to be fruitful. For, if we try to encase the Gospel in one historical-cultural form, we strangle the Gospel itself, turning it into a museum piece instead of a living faith:

As she perseveres in the preaching of the kerygma, the Church also needs to grow in the Amazon region. In doing so, she constantly reshapes her identity through listening and dialogue with the people, the realities and the history of the lands in which she finds herself. In this way, she is able to engage increasingly in a necessary process of inculturation that rejects nothing of the goodness that already exists in Amazonian cultures, but brings it to fulfilment in the light of the Gospel. Nor does she scorn the richness of Christian wisdom handed down through the centuries, presuming to ignore the history in which God has worked in many ways. For the Church has a varied face, “not only in terms of space… but also of time”. Here we see the authentic Tradition of the Church, which is not a static deposit or a museum piece, but the root of a constantly growing tree. This millennial Tradition bears witness to God’s work in the midst of his people and “is called to keep the flame alive rather than to guard its ashes” [3]

St. John Paul II understood good communication is necessary for the preaching of the faith. It requires more than the rote memorization of theological doctrine. “Where the preaching of the Gospel is concerned, care must not only be shown for the orthodoxy of its presentation but also for its incisiveness and its ability to be heard and accepted.” [4] Pride gets in the way of such communication. Only those who learn how to listen to others, to get to know them, to be at peace with them and their ways, will be able to properly communicate with others and share with them the peace of Christ. Oratory skills are nice, but rhetoric alone does not suffice. One needs to know one’s audience, and that requires learning to listen to them, to become like them, indeed to become one with them, so that the response is a communal instead of an individual response, showing everyone has a role.

The difficulties those in the Amazon have had in relation to the faith have often been the result of prideful people who, thinking themselves orthodox, have not lived authentic Christian lives. Orthodoxy is not orthodox without orthopraxy. In the Amazon, the bond of love has not been formed. The indigenous people find themselves separated from, and looked down upon, by those who brought the Christian faith into the region. The wisdom of the desert shows why such evangelization has gone astray and explains part of the reason why there is a great crisis of faith emerging in the Amazon. Colonizers tried to level down the area and create communities in their own image, using the faith as a tool for colonization, while the proper way of the church is inculturation, finding the way to lift up and complement the cultures it engages:

Inculturation elevates and fulfills. Certainly, we should esteem the indigenous mysticism that sees the interconnection and interdependence of the whole of creation, the mysticism of gratuitousness that loves life as a gift, the mysticism of a sacred wonder before nature and all its forms of life. [5]

When Christians live their faith properly, they are able to share the grace of Christ with the communities in which they live. Christians will work for both the physical and spiritual needs of those around them, just like Jesus, who was known to heal the sick and feed the poor while offering his saving grace to sinners. And they will not do it through some schema which judges other cultures as being inferior, but rather, they will integrate themselves to the community and change their own ways instead. They will not avoid their community, the feasts and celebrations of the culture at large, thinking it makes them superior to do so. Rather, they will integrate themselves into society and be its leaven, recognizing that the dough of the community is beyond themselves and not something which they need to make, as Pope Benedict XVI states:

The Church is firmly convinced that the word of God is inherently capable of speaking to all human persons in the context of their own culture: “this conviction springs from the Bible itself, which, right from the Book of Genesis, adopts a universalist stance (cf. Gen 1:27-28), maintains it subsequently in the blessing promised to all peoples through Abraham and his offspring (cf. Gen 12:3; 18:18), and confirms it definitively in extending to ‘all nations’ the proclamation of the Gospel”. For this reason, inculturation is not to be confused with processes of superficial adaptation, much less with a confused syncretism which would dilute the uniqueness of the Gospel in an attempt to make it more easily accepted. The authentic paradigm of inculturation is the incarnation itself of the Word: “‘Acculturation’ or ‘inculturation’ will truly be a reflection of the incarnation of the Word when a culture, transformed and regenerated by the Gospel, brings forth from its own living tradition original expressions of Christian life, celebration and thought”, serving as a leaven within the local culture, enhancing the semina Verbi and all those positive elements present within that culture, thus opening it to the values of the Gospel.[6]

The wisdom of the desert, the wisdom of Abba Motius, is the wisdom the church needs as it engages the world. It is the wisdom which recognizes that proper relationship between humility and praxis, which Jane Foulcher indicates was a part of the lesson Motius’s saying should give to us all:

There is, then, a delicate, even paradoxical, relationship between humility and practice. The efficacy of one’s practice is dependent on the prior presence of humility, yet, paradoxically, one’s receptivity to humility can be deepened through the practice of the monastic disciplines. Humility is not the direct product of external practices.[7]

Although it might seem like a celibate monk stuck in a desert cell would have little to nothing to teach us about evangelization and missionary work, in reality, the entry of the monks into the desert itself was a missionary activity which helped create and establish one kind of community based upon the Gospel. Its failures, and there were many, should remind us that there will be no utopia on other, but its successes demonstrate to us the way the Gospel spreads. The wisdom of Motius is one with the wisdom of the church it is embrace of inculturation, and it is the wisdom which lies behind Pope Francis’ exploration of inculturation in the Amazon. It is the wisdom of humility. Once we embrace it, we will find we can get through the snares which threaten to squash the authentic work of Christ.

[1] The Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Trans. Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984), 148.

[2] Pope Francis, Querida Amazonia. Vatican translation. ¶28.

[3] Pope Francis, Querida Amazonia, ¶66.

[4] St. John Paul II, Pastores gregis. Vatican translation. ¶30.

[5] Pope Francis, Querida Amazonia, ¶73.

[6] Pope Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini. Vatican translation. ¶114.

[7] Jane Foulcher, Reclaiming Humility: Four Studies in the Monastic Tradition (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2015), 75.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!