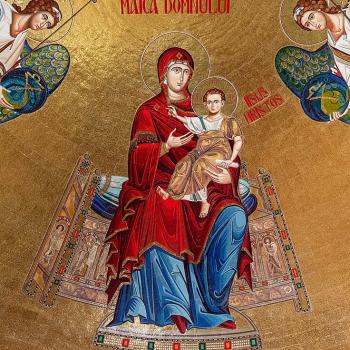

The Dormition of Mary, the “going to sleep” or death of Mary, and her subsequent assumption into heaven, is an important event in human history. It demonstrates to us what can be accomplished in and for us if we, like Mary, are open to Christ’s deifying grace in our lives.

The teaching of the Dormition in the Christian East is the teaching that Mary died, and it is only in and through that death she joined in with the death and resurrection of her Son, Jesus (through her assumption). Those who say she did not die do not follow ecclesiastical tradition, and try to separate Mary, not only from her Son, who died and rose from the dead, but form us, from the rest of humanity. She is human like the rest of us. She is the human source and foundation for the incarnation: she offered herself, and through her all humanity, to God. God accepted the gift, and made her human nature, her humanity, his own, so that all humanity, indeed, all creation, can partake of the deifying love of God.

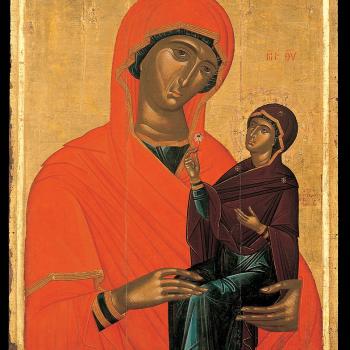

What is key is that Mary is human – perfectly human. It is important for her to be such so that she can offer that humanity to her Son, to grant him a real human existence, a real, undiluted humanity, uncontaminated by sin. Through it, be embraced humanity and truly lived as a human. She is his mother, and as his mother, she serves as his point of contact with the rest of human existence. Her humanity, her life, her death, all point to her embrace of God, her engagement with her Son; it is important to recognize this. She points to her Son. Any and all our understanding of her significance to salvation history, all the significance of the key events in her life, all point to and demonstrate some truth about her Son, and through her Son, about God (and also the human condition, as it is seen realized in him without any contamination of sin).

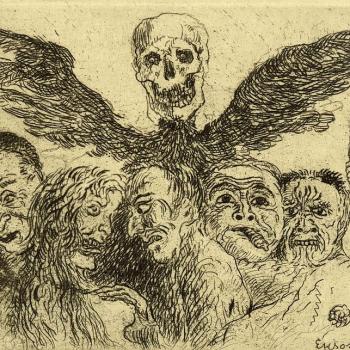

Thus, St. Andrew of Crete, contemplating upon Mary’s death and subsequent assumption into heaven, noted that in reflecting upon them, we must also consider her connection to her Son. He noted that everyone, including Jesus himself, has died, so it is not surprising that Mary should also die. It is a part of the human condition. But now, through the death and resurrection of Christ, death has been transformed; it is no longer filled with the sting of spiritual death and desolation; if we are no longer tied to sin, if we have been cut free from the slavery of sin, death now is able to transport us into heaven:

Simply this: if we are to touch on the mysteries of [Mary’s] supernatural departure, we must, at least briefly, turn our attention in the direction of our Lord and God Jesus Christ, and then, in proper order, link what we say about him to our subject today. For since it is the necessary lot of all human beings to die once (cf. Heb 9:27), since this is simply the inescapable fate of our nature – indeed, at the start of our history we received this sentence from our creator, because of our disobedience – for this reason the Lord died once and for all, becoming the ransom for the one death that faces us all, in order to free us all, in a single act, from death’s bitter tyranny: to free “those,” as the sacred writer says, “who all their lives were held fast in slavery by fear of death” (Heb 2:15). “What?”, some might ask; “shall we, then, not die that death?” Indeed, we shall die; but we shall not remain enslaved by death, as once we did when we were bound by it through the legal bond of sin.[1]

This, of course, is the key to understanding Mary’s death, and why it is important for us to not only remember it, but to reflect upon it and its meaning for us. Mary is human; she died, like everyone else. But her death is not the death of a sinner enslaved by sin; her death is the death of the beloved Mother of God, the perfect human, who, filled with grace, was all-holy and free from sin. Her death was able to lead her to her eschatological glory, dwelling with her Son in the kingdom of God. She who had become the home of the Son of God, found the Son of God became her home in her repose:

In this way, when you had suffered the death of your passing nature, your home was changed to the imperishable dwelling of eternity, where God dwells; and becoming yourself his permanent guest, Mother of God, you will not be separated from his company. For you became, in your body, the home where he came to rest, O Mother of God; and by your migration, O woman worthy of all praise, he is himself now the place of your repose.[2]

Mary, therefore, shows us what can happen in death; we can be transported into our eternal homeland. She, who carried the Son of God in her, finds herself carried by Him in eternity. But she is not the only one. She represents us all. She is, in this instance, represents every-man, every-woman, every-one, in their fulfilled state, in the natural purity of humanity, as it is embraced in eternity. The path from time to eternity is the path of death; it starts in time, indeed, in history, but finds its completion in eternity. Time, history, is not abandoned. We are not to accept any Gnostic rejection of the world. Rather, all that took place in time finds its place in the eschaton. The assumption of Mary’s body after her historical death demonstrates this to us. Her body is connected to the world at large, to time and space itself; the assumption of her body into heaven is the fulfillment of her earthly existence, but to have it fulfilled, it must also be affirmed and included in that fulfillment. Through her humanity, through her earthly history, we find ourselves connected to her, and so we already share, through her, the glory of the eschaton insofar as all those connections are assumed into heaven with her. This is why we remain connected with her, why we are able to express ourselves to her and feel her loving embrace over us. But now, we are called to follow her, to open ourselves up to the eschaton and realize the fullness of our own humanity, so that, with the grace of God, we too can be received into glory at the end of our earthly lives.

[1] St. Andrew of Crete, “Homily II on the Dormition” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 118.

[2] St. Germanus of Constantinople, “On the Most Venerable Dormition of the Holy Mother of God,” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 159.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!