St. Basil the Great tells us to glorify God as the “Master Craftsman,” for he created a wonderful, indeed, beautiful, world for us to live in. When we glorify him this way, we can be led from the beauty found in creation to the transcendent glory of God himself:

Let us glorify the Master Craftsman for all that has been done wisely and skillfully; and from the beauty of visible things let us form an idea of Him who is more than beautiful; and from the greatness of these perceptible and circumscribed bodies let us conceive of Him who is infinite and immense and who surpasses all understanding in the plentitude of His power.[1]

Goodness, truth, and beauty are the three great transcendental. All of them have God as their source. Because God establishes them, through his actions, he can be described by them, so that he can labeled as the Good, the Truth, and the Beautiful. Thus, as St. Gregory Palamas explains, even though God’s essence transcends all the categories of human thought rendering it is incomprehensible, we know God through his energies, through his actions, and we can use such actions and what they tell us about God to talk about God.

God’s beauty is made manifest in the beauty of his creation; the beauty we see around us participates in the beauty of God:

From the beauty of the limited creature, God makes known his own beauty that is in no way limited, so that the human being can return to God by these very same vestiges by which he turned away from him, in order that, because he turned himself away from the form of the Creator through love of the beautiful creature, he might return back again through the beauty of the creature to the beauty of the Creator.[2]

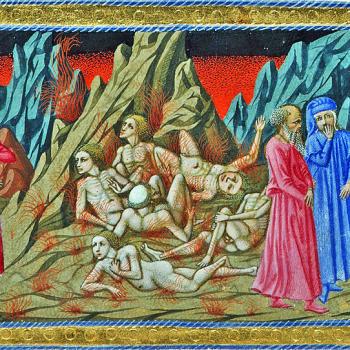

Just as limited goods participate in the Good, so that we should not undermine the Good by preferring lesser goods to it (which evil tempts us to do), so limited beauty participates in Beauty, and we should not undermine Beauty by preferring limited forms of beauty to it. Beauty, by nature, is attractive. Lesser forms of beauty have their attractions, so that someone of lesser character can use such beauty to lead people astray. That is, though beauty is something to be cherished, just like we should cherish whatever good we find, we should cherish it in proper fashion. For just as the good can be subverted as someone becomes inordinately attached to a lesser good, treating it as a greater good than it is, making the actions of those who do so “evil,” so beauty can be subverted as someone inordinately attaches themselves to its lesser form apart from its proper, holistic place in Beauty. This is not to say, when someone does this, the beauty fades away. Just as attachment to a lesser good does not remove that good, so attachment to lesser beauty does not diminish the beauty which is being embraced. But what is not embraced, what is rejected, is where ugliness or evil can be found. Evil is the absence of a good which should be there, so ugliness is the absence of the harmony which should be found in beauty.

While Beauty and the Good can be said to be one, because they are one in God, and so what is beautiful is good, we can attribute our relationship with beauty as being either good or bad based upon what we do with it. Those charmed by some beauty can be led to do all kinds of evil out of hope of taking control and possessing that beauty for themselves, while others, looking into the world, and the harmony presented by beauty, can be inspired to seek after what is good and just and indeed, work for the salvation of the world. Understanding this, S.L. Frank suggested, when considering beauty on its own, we can see it as something “neutral;” by itself, it will not save the world:

Beauty as such does not save him from the destructive forces of evil or from the tragic nature of human life. Beauty as such is neutral. In a sense it is indifferent to good and evil. Symbolizing some potential harmony of being, it peacefully co-exists with actual disharmony. Furthermore, according to Dostoevsky’s profound insight, beauty combines itself in the “divine” and the “demonic,” for wherever we are seduced by deceitful appearances, there we have dealing with the demonic. This lack of concord between beauty – esthetic harmony – and the genuine reconciling, redeeming essential harmony of being was manifested concretely with astonishing persuasive force in the tragic life-experiences of such artists as Botticelli, Gogol, and Tolstoy. We can say that beauty is a sign of the potential harmony of being, of the possibility of actual, fully realized harmony. And if the world were perfectly beautiful, it would be perfectly harmonious, in inner accord, free of tragic duality. Therefore the dream of the ultimate transfiguration of the world is a dream of the complete triumph of beauty in the world. But it is precisely only a dream, which is opposed by the bitter reality of the inner discord and duality of being. Beauty is only a reflection of “paradise,” of the ontological rootedness of all reality in divine total unity.[3]

Thus, there is the potential for demonic beauty, even as there is potential for angelic beauty. We can make a beauty which will impose fear and dread upon others as they look into it, using it to manipulate and control them. Tolkien, in the Lord of the Rings, represented this potential in the way Galadriel was tempted by the Ring – if she took its power, she would use it to lead the world with her beauty, but the world would be enslaved by it, enslaved by her and her charm:

And now at last it comes. You will give me the Ring freely! In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. And I shall not be dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night! Fair as the Sea and the Sun and the Snow upon the Mountain! Dreadful as the Storm and the Lightning! Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair.[4]

Galadriel understood the goodness of beauty, but also the dangers contained within it. We seek after paradise, but we can easily become subverted by a pale imitation of it. If we try to establish and hold onto such an illusory form of beauty, we will find ourselves lacking much of what is found in paradise, and in that lack, we will find evil. Those desperate to hold onto a form of beauty instead of to be penetrated and participate in the fullness of beauty will create a shallow illusion, one which is charming and yet without hope, without the joy which we expect from beauty itself.

This danger with beauty, however, applies only insofar as our attachment remains with a lesser beauty, whether it is some external lesser beauty, or our own internal beauty, which we enjoy because of the glory we think we already possess. The beauty that is there, insofar as it is there, is good, but it should remind us of the source and foundation of all beauty. We must not confine ourselves to that lesser beauty but seek after the source of beauty. When we do so, we will find that the beauty we had, the beauty we liked, was itself a part of the presence of that greater beauty, so that like Augustine we can end up saying:

Late have I loved Thee, O Beauty so action and so new, late have I loved Thee! And behold, Thou wert within and I was without. I was looking for Thee out there, and I threw myself, deformed as I was, upon the well-formed things which Thou hast made. Thou wert with me, yet I was not with Thee. These things held me far from Thee, things which would not have existed had they not been in Thee. Thou didst call and cry out and burst in upon my deafness; Thou didst shine forth and glow and drive away my blindness; Thou didst send forth Thy fragrance, and I drew in my breath, and now I pant for Thee; I have tasted and now I hunger and thirst; Thou didst touch me, and I was inflamed with desire for Thy peace.[5]

Beauty is good and glorious, but our use of it is not always such. We should find the goodness in beauty. We should find out how it points to the source and foundation of all beauty, God and use it to direct us to God to find and attain that beauty which we love and desire, not just in its lesser forms, but in its greatest form, one which is with God and so eternal. Therefore, let us glorify God, taking the beauty we find and use it to lift us up to the infinite beauty and goodness found with God, a beauty so sublime, so great, we will never attain its limits and so it will always give us the hope and joy which we need to truly thrive.

[1] St. Basil the Great, “Hexaemeron” in Saint Basil: Exegetic Homilies. Trans. Agnes Clare Way, CDP (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1963), 19.

[2] St. Isidore of Seville, Sententiae. Trans. Thomas L. Knoebel (New York: Newman Press, 2018),40.

[3] S. L. Frank, The Unknowable: An Ontological Introduction To The Philosophy of Religion. Trans. Boris Jakim (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2020), 196.

[4] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1966), 381.

[5] St. Augustine, Confessions. Trans. Vernon J. Bourke (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1953; repr. 1966), 297.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!