There is a tendency among some Catholics to suggest that Catholic teaching has not developed or changed over time. If they studied history, they would know differently; indeed, if they studied the saints and major thinkers throughout the centuries, they would see how change has been incorporated within Catholic tradition and recognized as serving an important way for the Holy Spirit to direct the church. Nicholas of Cusa, an important fifteenth century theologian, philosopher, and canon lawyer, indicated that church teaching could change in such a way that what was once presented as doctrine could even be rescinded: “I have already told you that it is possible for the entire Church to hold some doctrine now and afterwards to prohibit it, but there is no peril to the salvation of souls in this.”[1] Nicholas said that this could be seen in the authority granted to the Pope:

And this change is not like depending on the lesser authority of Christ as teacher, since the Church, which is the body of Christ and quickened by His Spirit, does nothing other than what Christ wishes. And so the change of interpretation depends on the will of Christ, who now wills it so by His inspiration, just as once this very precept was practiced otherwise, according to the needs of the time. And, therefore, this power to bind and loose is no less in the Church than in Christ.[2]

Development certainly must stand upon and come from what came before it; it is not arbitrary, but rather is guided by principles which were not always properly understood and followed but, over time, were engaged and used to develop the church’s understanding of what has been handed to it in the deposit of faith. This is exactly what we see has happened in our time concerning the death penalty: the Holy Spirit directed the church to consider the implications of its belief in human dignity and the value of human life, leading it to realize that the only logical conclusion is that capital punishment must be utterly denounced and rejected as a legitimate option in civil society. From the time of St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, to Pope Francis, we see the church finally coming to grips with the implications of the death penalty and see how its practice stands against not only the teachings of Christ, but what can be discerned through natural law as well. Initially, there was a general rejection of the practic, though the church indicated that extraordinary circumstances might justify its use; upon further reflection, even those exceptions were denied. This shows us the pattern of how such developments occur in church history; first, there is a general principle which is stated, one which nonetheless allows the possibility of some form of exception; then those exceptions are examined, especially when they are being used to deny the general principle, and excised as well. We see this in the way church worked its way to the complete and utter condemnation of slavery.

At first the church accepted slavery as a part of society, though it suggested that the humanity of slaves should be remembered and slaves should not be abused (without always being clear as to what constituted such abuse). Even saints like Salvian, who fought for various aspects of social justice, accepted that slaves would always be a part of society, though he often pointed out the moral superiority of slaves and the terrible injustices they faced at the hands of their rich masters:

Murder is rare among slave because of their dread and terror of capital punishment, but it is common among the rich because of their hope and trust in impunity. Perhaps we are wrong in putting in the category of sins what the rich men do, because, when they kill their slaves, they think that it is legal and not a crime. Not only this, they abuse the same privilege even when practicing the filth of unchastity. How few among the rich, observing the sacraments of marriage, are not dragged down headlong by the madness of lust? To how few are not home and family regarded as harlots? How few do not pursue their madness towards anybody on whom the heat of their evil desires centers? [3]

There were a few, all too few, Christians like St. Gregory of Nyssa who entirely repudiated the notion of slavery, but in general, Christians accepted the social order as it existed when Christianity entered the world and only worked to lessen the worst offense of the system instead of overturning it. This, of course, gave many who would defend the slave trade the resources they needed to do so, which is why, when the church began to take the issue seriously, we find many responding to the church by presenting what they found in history as a reason to ignore the new conclusions the church was making concerning its practice.

It is important to note how we got to the place we are today. Though we can look back to Rome, and what Christianity experienced and accepted from the culture at large, it was really since the time when Western Europeans began exploring and colonizing the world we find the rise of the modern institution of slavery, because new lands provided all kinds of peoples for colonial powers to enslave. Thus, as Shannen Dee Williams indicated, we see in the 15th century the church allowing various peoples to enslave those who did not convert and become Christian:

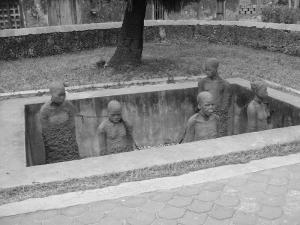

In the 15th century, the Catholic Church became the first global institution to declare that Black lives did not matter. In a series of papal bulls beginning with Pope Nicholas V’s Dum Diversas (1452) and including Pope Alexander VI’s Inter Caetera (1493), the church not only authorized the perpetual enslavement of Africans and the seizure of “non-Christian” lands, but morally sanctioned the development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. This trade forcibly transported at least 12.5 million enslaved African men, women and children to the Americas and Europe to enrich European and often Catholic coffers. It also caused the deaths of tens of millions of Africans and Native Americans over nearly four centuries.[4]

When Popes began to be more critical of slavery (especially in the early 19th century), they ended up being more critical of the slave trade, that is, the buying and selling of slaves, than they were of the practice of slavery itself. While many think this would suggest that the church rejected slavery itself, for if the slave trade were forbidden, slavery itself should end, we see in reality that many saw this as leaving behind a major loophole, similar to the kind of loophole Pope John Paul II left in relation to the death penalty. Because of this, many Catholics within the United States, including and especially bishops, priests, and religious, found a way to justify their continued use of slaves for their own interests:

It astonishes us because we don’t realize how deeply slavery was embedded in our economy. Slavery fueled the growth of many of our contemporary institutions, including the Catholic Church. Many of us view the Catholic Church as a Northern church. But the Catholic Church established its foothold in the South and relied on plantations and slave labor to help finance the livelihoods of its priests and nuns, and to support its schools and religious projects. This is history that we all should know. But we don’t. Enslaved people have largely been left out of the origin story that is traditionally told about the Catholic Church and other religious institutions.[5]

As the church was wrestling with the implications of slavery, many used all the means left to them to defend its practice. We can see this the way that John England, the first bishop of Charleston, South Carolina (September 21, 1820 – April 11, 1842), affirmed that those who had slaves could continue to keep and use them, even as those who would voluntarily become slaves could, likewise, become slaves, giving a way for slavery to continue while affirming with various Popes the condemnation of the slave trade itself, as Paul Lakeland explained:

John England’s defense of slavery is composed in what must for him have been a tricky political situation, but it is nevertheless a disturbingly shoddy argument. He bases his claim that while the slave trade is evil, slavery itself as it then existed in the United States was morally neutral, on a dubious application of natural law. God’s law gives every person the right to self-determination, and therefore an individual can, if he or she wishes, voluntarily enter a lifelong state of servitude. Many people have done this over the years, and he believes there are many benefits to being a slave. Indeed, he adds, he knows quite a number of former slaves who regret their manumission.[6]

England suggested that natural law allowed for the use of slaves, but he also said that he did not like the use of slaves and would not “establish it “where it did not exist.”[7] Worse than England, we have the example of Patrick Lynch, the bishop of Charleston from 1857 to 1882, who not only defended slavery, he defended the Confederacy, accepting a position within the Confederacy itself, as he was sent to Rome by the Confederacy to try to garnish Rome’s support for their cause (while also writing a pamphlet defending slavery).

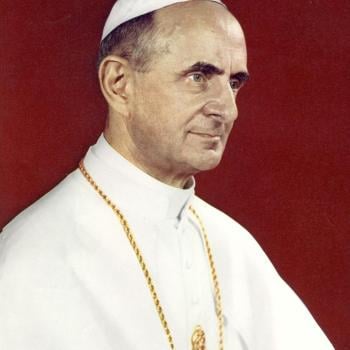

It is due, in part, with the general rejection of the slave trade, and with it, the emancipation of slaves, that Pope Leo XIII was able to go forward and proclaim the church’s rejection of slavery, doing so with no uncertain terms. While there were condemnations of various aspects of the slave trade before him, it took Pope Leo XIII to state:

In the presence of so much suffering, the condition of slavery, in which a considerable part of the great human family has been sunk in squalor and affliction now for many centuries, is deeply to be deplored; for the system is one which is wholly opposed to that which was originally ordained by God and by nature.[8]

Leo made it clear, natural law could not and should not be used to justify slavery. It was a sin against nature, and its continued use, and the system which surrounded it (which is more than merely the buying and selling of such slaves) must be rejected:

We, indeed, who are holding the place of Christ, the loving Liberator and Redeemer of all mankind, and who so rejoice in the many and glorious good deeds of the Church to all who are afflicted, can scarcely express how great is Our commiseration for those unhappy nations, with what fullness of charity We open Our arms to them, how ardently We desire to be able to afford them every alleviation and support, with the hope, that, having cast off the slavery of superstition as well as the slavery of man, they may at length serve the one true God under the gentle yoke of Christ, partakers with Us of the divine inheritance. Would that all who hold high positions in authority and power, or who desire the rights of nations and of humanity to be held sacred, or who earnestly devote themselves to the interests of the Catholic religion, would all, everywhere acting on Our exhortations and wishes, strive together to repress, forbid, and put an end to that kind of traffic, than which nothing is more base and wicked. [9]

Though there was considerable efforts to limit and end the slave trade, especially within the 19th century, earlier declarations were examined and accepted as being limited in scope by those who supported and used slaves themselves. There was needed a full and complete condemnation of the practice, one which entailed a rejection of all claims of natural law for its use, which is exactly what Pope Leo XIII provided. Since we were not alive when this change happened, we often do not realize how significant a change this entailed, for what Pope Leo did was put an end to all loopholes which were used to allow the continuation of slavery in the world. It is this kind of change which we see happening today in regards the death penalty; loopholes once accepted are being denied, and with it, natural law arguments which once were used to support the death penalty now are overturned by other natural law arguments, ones which talk about the dignity of value of life itself is so great that no one has the right to directly and intentionally take it from another:

There is yet another way to eliminate others, one aimed not at countries but at individuals. It is the death penalty. Saint John Paul II stated clearly and firmly that the death penalty is inadequate from a moral standpoint and no longer necessary from that of penal justice. There can be no stepping back from this position. Today we state clearly that “the death penalty is inadmissible” and the Church is firmly committed to calling for its abolition worldwide. [10]

The development of doctrine in the church is real. It has been used to help explore issues such as Christology, ecclesiology, and soteriology. It has also been used to promote changes in what is and is not seen as acceptable behavior in the world. Just as we cannot go backwards and once again accept slavery, so we cannot go backwards and accept the death penalty. Both changes, of course, follow principles which flow from the Gospel (and the church’s understanding of the moral law). They do not go against, but further affirm, what has been handed to it. As the church continues in history, as the church continues to develop, it is likely we will find more such principles leading to more such changes; when we do so, we must, like Nicholas of Cusa, recognize it is a sign of the times we live in and follow the church in its changes.

[1] Nicholas of Cusa, “Dialogue Against The Amedeists” in Nichola of Cusa: Writing on Church and Reform. Trans. Thomas M. Izbicki (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 317 [He gave as an example changes in the way baptism was performed].

[2] Nicholas of Cusa, “To the Bohemians” in Nichola of Cusa: Writing on Church and Reform. Trans. Thomas M. Izbicki (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 29.

[3] Salvian the Presbyter, “The Governance of God” in The Writings of Salvian the Presbyter. Trans. Jeremiah F. O’Sullivan (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1962), 98-9.

[4] Shannen Dee Williams, “The Church Must Make Reparation For Its Role In Slavery, Segregation” in National Catholic Reporter (6-15-2020).

[5] James Devitt, “’The Reckoning is Real’: On Slavery, The Church, And How Some 21st-Century Institutions Are (Finally) Starting to Talk About Reparations” in NYU (3-2-2020).

[6] Paul Lakeland, “The Complicated Legacy Of Bishop John England” in Commonweal (11-25-2020).

[7] Paul Lakeland, “The Complicated Legacy Of Bishop John England.”

[8] Pope Leo XIII, In Plurimis (5-5-1888). ¶3.

[9] Pope Leo XIII, In Plurimis, ¶19.

[10] Pope Francis, Fratelli tutti. Vatican translation. ¶263.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!