The reality of the eucharist is Christ; no matter what accidents are associated with the reception of the eucharist, be it bread or wine, it is always Christ, always fully Christ, and not a part of Christ which is received. While we might understand and believe the truth, in the “age to come,” we will continue to receive the reality of the eucharist, and we do so without the need of physical accidents symbolizing the truth which is being received:

The body of Christ is received presently under an appearance, that is, sacramentally, in order to signify that union by which we will be conformed to God. This will happen when we will see Him as He is. Nevertheless, those who receive [the Eucharist] worthily do not receive less than the reality itself. And it is not surprising that this receiving [of the body of Christ] is a sign of some union, considering that all things whatsoever that are in the Church on earth are signs of future realities. For in the future there will be no things that are signs of other things. And this is what it means to receive by the truth of the reality, that is, not figuratively. [1]

As the accidents of the eucharist are those of bread and wine, they take on physical qualities of bread and wine. We must not confuse the physical size and weight of what we receive as representing how much of Christ we received. We always receive the same thing, the fullness of Christ, no matter how much of the accidents we receive. A small piece of bread or a large piece of bread contains the same Christ: size does not matter. Likewise, as every piece of the bread is fully Christ, as the bread together is the same Christ. There is no substantial or essential difference between the two. We can talk about the accidents and so talk about there being many pieces of bread, but there remains one Christ, and it is the same Christ with one piece or multiple pieces of bread. The accidents can be quantified, allowing us to describe them as a plurality, but the essence is one. We must not confuse talk about a plurality in the accidents as affecting the essence of the eucharist. Similarly, the church is one, though it contains a plurality of persons; no matter how many people are involved, there is one church, and behind that one church there is one body of Christ. “For as in one body we have many members, and all the members do not have the same function, so we, though many, are one body in Christ, and individually members one of another”(Rom 12:4-5 RSV).

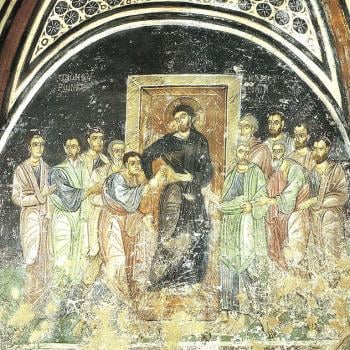

There is but one Christ at work in and through Christians no matter how many Christians are acting as agents for Christ. Christ is at the center of the church, the communion of saints, acting as the high priest who sacrifices himself as the sacrificial victim. “In the place of Solomon’s temple, Christ has built a temple of living stones, the communion of saints. At its center, he stands as the eternal high priest; on its altar he is himself the perpetual sacrifice.” [2] Thus, where two or more members of the church come together, Christ is with them in their midst, acting as the high priest on their behalf, giving them the graces which they need. “Again I say to you, if two of you agree on earth about anything they ask, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven. For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matt. 18:19-20 RSV). It is the same Christ when it is two people, three people, a whole ecclesial community, or the whole church coming together. Their unity together as the body of Christ, bringing the reality of Christ in the midst of them, is what allows the church to be catholic. All divisions in the body of Christ are overcome by Christ. Just as when we consider the quantity involved in the accidents of the eucharist does not change the quantity or quality of Christ, even if the accidents are moved around and separated from each other, so divisions within the community do not overcome the unity which is established in and through Christ himself. “The way of the catholicity of the Church is revealed in the eucharistic community shows that the ultimate essence of catholicity lies in the transcendence of all divisions in Christ. This should be understood absolutely and without any reservations.” [3]

While we can speak of many hosts or pieces of bread when talking about communion, realizing that there is but one Christ no matter the accidents involved, so there is but one church, one body of Christ, indeed one Christ connecting all Christians together. We can talk about a plurality of members of the body of Christ, but this does not change the oneness of the body of Christ itself. “For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body — Jews or Greeks, slaves or free — and all were made to drink of one Spirit” (1 Cor. 12:12-13 RSV).

The prayer of the people, the prayer of the church, is the prayer of the body of Christ, or, as St. Edith Stein said, “The prayer of the church is the prayer of the ever-living Christ.” [4] Whatever the people of the church do together, they do as the one body of Christ, and it is one Christ at work within them. We can speak of the plurality of the persons involved, the plurality of the instruments or agents of Christ, and if we are speaking of ourselves as those agents, we can do so by saying “we,” without rejecting the way it is one Christ, one church, which is at work (similar to the way speaking of the plurality of the accidents of bread and wine does not negate the one Christ being received in communion). Indeed, the church often speaks communally as a we which is why Origen says the church does so in her confession of faith:

For the Church when it says, “We shall confess to you, God, we shall confess to you,” is persisting in confession; it will not confess just once, but often, which is evident through the confession, because a second time, “we shall confess,” and next, “we shall call upon your name.” [5]

When the church is at work, it is Christ at work; no matter how many people are involved, they work together as one thanks to Christ who is at work in them. This is especially true in regards the sacraments: Christ works through human agents for their actualization:

The explanation of this as follows: Our restorative principle, namely, the incarnate word, in so far as He is God and man, instituted the sacraments for the welfare of men and ordained, as was fitting, that they may be performed for men through the agency of men to preserve the conformity of the dispenser to the Savior Christ and for the salvation of man himself. Because Christ the Savior saved the human race in conformity with justice, the dignity of order and the certainty of salvation – for He devoted Himself to our salvation in a right, orderly, and certain manner – it follows that for these three reasons He has commissioned the administering of the sacraments to man. [6]

The plurality of the agents involved in human history does not negate the one Christ who is at work in and through them. Christ is always the high priest, and it his work as the high priest which allows the sacraments to be effective. But we must also keep in mind, this is also true in the establishment of the church, which is itself a sacrament, and it is as a sacrament the church has its part in the execution of other sacraments:

The Church is the mystery of the world, which is manifested as sacraments. Therefore, sacrament can be most generally defined as the manifested action of the Church in man. Man is the temple, the sanctuary, the priest, the bringer of sacrifice, and the receiver of sacrifice. The Church herself, the sacrament of sacraments, is not a particular institution, as each of the specific sacraments are. Rather, she is, on the one hand, a sacred fulfillment, the fulfillment of God’s original design, of “the dispensation of the mystery, which from the beginning of the world had been hid in God” (Eph. 3:9). On the other hand, she is the unique and supreme reality of Divine-humanity, revealed by Christ expressly at the Last Supper. The is the sacramental attestation to the Incarnation; the institution of the sacrament of the Eucharist is a manifestation of or attestation to the Incarnation. The mystery of the Church, this sacrament of sacraments, precedes and grounds the sacraments. [7]

The sacraments are not only administered by the church, they are also received by the church, and it is through both that the church is able to realize who she is: “The sacraments are not only something which is administered by the church, but they are also and really the self-actualization of the church, and indeed both in the one who administers the sacrament and in the one who receives it.” [8]

The church is one and many; the people within the church are many but they are united as one in Christ, even as the persons of the Trinity are one. “The glory which thou hast given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, I in them and thou in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that thou hast sent me and hast loved them even as thou hast loved me” (Jn. 17:22- 23 RSV). The people of the church are one, not only with each other, but with Christ, so that in their unity, there is always one Christ at work in, through, and with them. This is true especially in relation to the church and her execution of the sacraments. There is always one Christ at work in their execution, and yet, there is a plurality of people involved in their execution. This means that all sacraments have a communal aspect to them. “Another fundamental implication is that no ministry in the Church can be understood as outside the context of the community.” [9] There is no priesthood, no orders without the community, nor is there a community without some sort of unity in Christ manifested through the priesthood:

The principle that the “one” is inconceivable without the “many.” In practical canonical terms this is expressed in various ways: (a) there is no ordination to the episcopate without the community. Since ordination is an act which is ontologically constitutive of episcopacy, to condition the ordination of the bishop by the presence of the community is to make the community constitutive of the Church. There is no Church without the community, as there is no Christ without the Body, or the “one” without the “many.” (b) There is no episcopacy without a community attached to it. [10]

Thus, the unity of the church as the one body of Christ, where Christ is always found wherever the people come together, does not undermine the plurality of the people, just like the oneness of God does not do away with the persons of the Trinity:

God thus leads all created beings, all the “particular relations” of the distinct natures, to an unconfused union without abolishing their natural differences. This demonstrates the reference of each one to the wholeness of being, the totality of common, created and caused nature in relation to its one, single, uncreated, and supernatural Cause. God demonstrates, I would say, the consubstantiality of created beings, not by negating the differences of natures, but by joining them without confusion in a harmonious and undivided integrating “identity,” which is ontological because he is “cause, principle, and end of all, the creation and beginning of all things and eternal ground of the circuit of things.” [11]

Just as the persons of the Trinity can reveal their plurality-in-unity through the use of the plural pronoun “us” (cf. Gen. 1:26), so the plurality of the persons in the church, if they were to engage that plurality-in-unity with the pronoun “we,” would not undermine the oneness or unity of the church itself. This is why using “we” when talking about the way Christ works through the church, through the people of the church as ministers of the sacraments, should not be seen as necessarily undermining Christ’s central role in the execution of the sacraments.[12] “Christ is the one who distributes the charisms through the sacraments, and each such charism is Christ himself in a special and distinctive (idiotropon) incarnation of him.” [13] Christ, therefore, fulfills the incarnation in and through the church which is one with him, not apart from her.

“The Incarnation of Christ accomplishes the unification of divine and creaturely life, of man’s deification, which is precisely the power of the heavenly Church manifested in the earthly Church.”[14] The church in history is meant to call people to salvation and present to the world the sign of that salvation, offering hope and grace to all. “The sacramentality of the church’s basic activity is implied by the very essence of the church as the irreversible presence of God’s salvific offer in Christ.” [15] The church must not forget this, which is why the church must always be at work in the world presenting that offer to all, realizing that many can and will receive it in ways which will only be revealed in the eschaton. Indeed, in the eschaton, many of those who might have appeared not to have been joined with Christ, joined with the church, will be revealed as mysteriously having been one with Christ and so a part of the church (cf. Matt. 25:31-40). For we must accept that God is at work in the world in such a way that God is not bound to the sacraments and the institutional church for providing sacramental graces to those in need. This is why St Thomas Aquinas, for example, suggested angels could be involved in giving out such graces:

But it must be observed that as God did not bind His power to the sacraments, so as to be unable to bestow the sacramental effect without conferring the sacrament; so neither did He bind His power to the ministers of the Church so as to be unable to give angels power to administer the sacraments. And since good angels are messengers of truth; if any sacramental rite were performed by good angels, it should be considered valid, because it ought to be evident that this is being done by the will of God: for instance, certain churches are said to have been consecrated by the ministry of the angels [See Acta S.S., September 29]. But if demons, who are “lying spirits,” were to perform a sacramental rite, it should be pronounced as invalid. [16]

The church is one, it is the body of Christ, and in it there is a plurality of persons, a plurality which does not undermine its unity and oneness. Christ is found in and with each person of the church as well as in the church as a whole. The church’s mission is the mission of Christ, to spread grace to the world, helping the world come together as one and partake of the kingdom of God. “The Church is the fulfillment of God’s eternal plan concerning creation and the salvation, sanctification, glorification, deification, and sophianization of creation. In this sense, the Church is the very foundation of creation, its inner entelechy. The Church is Sophia in both of her aspects.”[17] We must not confuse the inner nature of the church with the institution and the defects of the institutional church in history; while the church subsists in the institutional church, the church transcends its institutional form. This recognition is important so that we do not get lost in clericalism nor suggest that those who do not seem to be within the institutional church cannot be a part of the church and saved in and through her.

[1] Robert of Melun, “Questions on the Divine Page,” in Interpretation of Scripture: Practice. Trans. Franklin T. Harkins. Ed. Frans van Leiere and Franklin T. Harkins (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2015), 302.

[2] St. Edith Stein, “The Prayer of the Church” in The Hidden Life. Trans. Waltraut Stein, PhD (Washington, DC: ICs Press, 1992), 9.

[3] John D. Zizioulas, Being As Communion (Crestwood, NY:. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1997), 162.

[4] St. Edith Stein, “The Prayer of the Church,” 7.

[5] Origen, Homilies on the Psalms: Codex Monacensis Graecus 314. Trans. Joseph W. Trigg (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2020), 221[Homily Psalm 74].

[6] St. Bonvaventure, Breviloquium. Trans. Erwin Esser Nemers (St Lois: B. Herder Book Co.., 1946), 186.

[7] Sergius Bulgakov, Bride of the Lamb. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 273.

[8] Karl Rahner, Foundations of Christian Faith. trans. William V. Dych (New York: Seabury Press, 1978), 427-8.

[9] John D. Zizioulas, Being As Communion, 163.

[10] John D. Zizioulas, Being As Communion, 137.

[11] Nikolaos Loudovikos, Church In the Making: An Apophatic Ecclesiology of Consubstantiality. Trans. Normal Russell (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2016), 45 [Quoting Maximos Mystagogy 665BC].

[12]“ I answer that, As stated above (Article 5), since the minister works instrumentally in the sacraments, he acts not by his own but by Christ’s power. Now just as charity belongs to a man’s own power so also does faith. Wherefore, just as the validity of a sacrament does not require that the minister should have charity, and even sinners can confer sacraments, as stated above (Article 5); so neither is it necessary that he should have faith, and even an unbeliever can confer a true sacrament, provided that the other essentials be there,” St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica. trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1948), III-64.9.

[13] Nikolaos Loudovikos, Church In the Making: An Apophatic Ecclesiology of Consubstantiality, 105.

[14] Sergius Bulgakov, Bride of the Lamb, 257.

[15] Karl Rahner, Foundations of Christian Faith, 413..

[16] St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, III-64.7.

[17] Sergius Bulgakov, Bride of the Lamb, 253.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!