Paul spoke to the elders of Ephesus, explaining to them that their authority in the church should be exercised for the sake of the people, and not for their own personal gain:

Take heed to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God which he obtained with the blood of his own Son. I know that after my departure fierce wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock; and from among your own selves will arise men speaking perverse things, to draw away the disciples after them. Therefore be alert, remembering that for three years I did not cease night or day to admonish every one with tears. And now I commend you to God and to the word of his grace, which is able to build you up and to give you the inheritance among all those who are sanctified. I coveted no one’s silver or gold or apparel. You yourselves know that these hands ministered to my necessities, and to those who were with me. In all things I have shown you that by so toiling one must help the weak, remembering the words of the Lord Jesus, how he said, `It is more blessed to give than to receive (Acts 20:28-25 RSV).

Bishops, priests and other clergy should be good pastors, seeking to help the church, doing what they can to protect their flock from harm, that is, from various evil, including, and especially, the evil which could come from themselves. If a bishop were to exercise their authority for the sake of their own gain, they would scandalize the faithful, and instead of acting as a faithful shepherd for their flock, they would be acting like a ravaging wolf going after easy prey.

A bishop should not use false pretenses to criticize and harm one of their flock. If they were to do so, their injustice would lead to great scandal. People would be confused as to what they saw happening and would ask questions, indeed, some might end up questioning their faith, thinking that if what the bishop did represented the faith, they would want nothing to do with it. If and when this begins to happen, the bishop should see where they went wrong, and correct their mistake; if, on the other hand, they try to defend themselves using faulty logic to do so, they only increase the harm which they have caused, as their claims will certainly cause many to go astray.

Thus, a bishop should not use their power to criticize and abuse someone they do not like, accusing them of doing something which they have not done. Nor should they ignore proper distinctions, conflating what should not be conflated, such as suggesting all intrinsic evils are grave evils, because when they do this, ordinary people become confused and follow the distortions being suggested. Heresy forms out of such confusion, and if the heresy is not quickly stopped, it can cause great problems in the church. This is exactly what we saw happen during the Arian crisis.

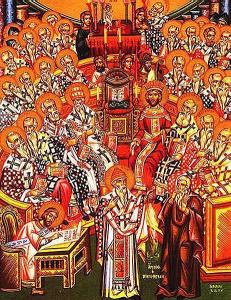

One of the problems of Arius, and those who followed his teaching (which included many bishops), was the way he interpreted the Father’s begetting of the Son as indicative of the Logos being a contingent being. Once the Son was shown to be a contingent being, Arius then said that this meant the Son was not eternal, meaning, the Son was not God. Thanks to the chaos and strife which Arius and his followers brought to the church, Christian unity was torn asunder. To deal with the problem, Constantine, and his advisors, suggested that the Christian hierarchy should come together and establish a unified presentation of the faith. And so Constantine called for the Council of Nicea in 325. At it, the council established the Nicene Creed, presenting the way they thought was best to express the relationship between God the Father and God the Son, showing how they are both divine and yet distinct from each other. They believed it was necessary to use the term homoousios, “of the same being or essence,” in the creed as a way to explain that relationship, for by its use they could indicate that the Father and the Son (and also the Holy Spirit) were equally God.

The term homoousios was deemed necessary because, when creeds were suggested which did not use it, the declarations in them turned out to be ambiguous, allowing both Arians and non-Arians to read their position into what was written. After its use was accepted, it took time for Christians to understand all the implications of its use (as well as making sure bad applications of its use, some of which were already existent before Nicea, were rejected). In the end, scripture would influence the way Christians interpreted the word homoousios even as the word would influence the way Christians read scripture. More than any other book, the Gospel of John gave Christians the means to do this. For it was John which provided the best texts to show Jesus’ underlying divinity, the truth which the inclusion of the word homoousios in the Nicene Creed was meant to reinforce. Thus, when Jesus talked about the unity and glory he shared with the Father, a glory which he had “before” the incarnation, and which he was once again to receive, the homoousios was able to be used as a way to understand the way Jesus could share the Father’s glory

I glorified thee on earth, having accomplished the work which thou gavest me to do; and now, Father, glorify thou me in thy own presence with the glory which I had with thee before the world was made. I have manifested thy name to the men whom thou gavest me out of the world; thine they were, and thou gavest them to me, and they have kept thy word. Now they know that everything that thou hast given me is from thee; for I have given them the words which thou gavest me, and they have received them and know in truth that I came from thee; and they have believed that thou didst send me. I am praying for them; I am not praying for the world but for those whom thou hast given me, for they are thine; all mine are thine, and thine are mine, and I am glorified in them (Jn. 17:4-10 RSV).

Because Jesus is said to be the “Son of God,” it is as a Son, begotten of the Father throughout eternity, he is said to have all the things given to him by the Father. Everything the Father has, including divinity, including the divine glory, is given to the Son by being begotten of the Father. The Father’s “nature” is given to the Son, making them homoousios. This is why, “before” the incarnation, the Son shared with and had the Father’s glory, the glory of the divine nature. In his kenosis, he emptied himself, so that in and through his assumption of a human nature, he possesses a nature which does not possess in itself the fullness of that glory. Nonetheless, as Jesus asks to have that glory shown to the world, that glory is presented to us in the economy of the incarnation. This is especially true in regards Jesus’ resurrection, for in and through it, the Father glorifies the Son, affirming to us the glory which the Son had before the incarnation, showing the world that indeed all that the Father has, the Son has in eternity. Once again, the word homoousios is capable of providing us the means of understanding this by showing that all that the Father has is the divine nature which then the Son also has. Thus, the relationship of the Father and the Son is manifested in the economy of the incarnation; we should not confuse the human nature of the Son as all that the Son is, for then we would end up like the Arians, thinking the Son is a mere creature. We should rather understand that that Son, the eternal Logos, reached down and revealed to us the truth of his relationship with the Father in a conventional form (his human nature), not confusing the conventional representation of the truth with the absolute truth but rather understand how it points to and manifests the absolute truth, God, to the world.

Arius, therefore, confused the kenotic form of the Logos revealed to us in the incarnation, that is the created nature the Logos assumed, as all that the Logo was. His misunderstanding of the faith led many astray. The faithful needed the shepherds of the church to provide a proper response to Arius’ claims, and the bad hermeneutic he used to interpret Scripture. This is what they did at Nicea, especially with the way they brought in the term homoousios as a way to engage the relationship between the persons of the Trinity. They knew that they best way to respond to Arius was to build up the faithful, to help them with the tools they needed to overcome Arius’ misinterpretation of the faith. This is what bishops should always be doing: building up the church, helping the faithful when they are confused. They should understand that the role they have been given is of a servant; they should not see the power they have been given is for their own benefit, but rather, for the sake of the church. Thus, if and when they need to speak, they should do so with love and compassion, and not as a triumphant demonstration of their authority, nor worse, as a way to generate wealth and donations. If they do that, they call into question their exercise of power, for it seem, more than anything, they are doing a stunt to bring attention to themselves. Acting in such a way shows they are not acting in good faith; they are not engaging people out of compassion, and that is exactly what bishops should be doing, working out of compassion, for that is exactly what Paul said should guide the actions of ecclesiastical authorities. What bishops should be doing, then, is toiling for the sake of the people, not their own ambitions, or worse, their own political ideologies. The power they have should not be abused, and if they use it to unjustly threaten or undermine others, they risk bringing the judgment which they want to give to others upon themselves.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!