While God has revealed various elements of the eschaton to us, and we can and do participate in it in part now because the eschaton has been immanentized, we must be careful and not claim to know more about it than we really do. We can, and will, develop theological opinions, using revelation as the foundation for our ideas. However, we must always be humble and recognize how limited we are in establishing our eschatological theories, accepting the fact that what will be will likely be far different from anything which we can guess. So long as we are bound by various limitations, such as those imposed upon us by temporality, the eschaton will transcend us. We can and should believe what has been revealed is true, but we must also recognize what has been revealed is often paradoxical in nature; though there are many ways we could try to resolve the paradox handed to us, none of them truly satisfy us, because we know that such resolutions tend to undermine elements of revelation to do so (and, of course, much of our lived experience also calls such resolutions to question). We must accept that the resolution of the paradox will reveal itself to us in due time, that is, in and with the eschaton itself, and so the fullness of the truth will apprehended by us only in our own complete integration with the eschaton itself.

Again, it cannot be stated enough, we should therefore engage eschatological questions with due humility, understanding and recognizing our limitations, so that we do not make more out of our suggested solutions than we should. This does not mean we are left without any understanding. For, thanks to revelation, we can deny various suggestions, such as the notion that God plans to annihilate everything. We can and use revelation to deny all those who would threaten to undermine the hope given to us by Christ. For we must remember, the revelation of God in Christ is a revelation meant to give us hope, to be good news, and so we can and should engage eschatological questions with such hope serving as the foundation for all our theological reflections. That is, we must take into consideration God’s desire for us, for the world, the desire that all will be saved:

Verily, God can never deny to the human race a knowledge of the way of salvation, since he wishes that all men should be saved, according to the Apostle. And his goodness is infinite, wherefore he has always left men the means by which they might be enlightened to gain a knowledge of the ways of truth. [1]

It is Satan, not God, who desires the damnation of humanity (and the destruction of the rest of creation):

But God, in the ancient plan that He had in Himself before the ages, considered how He could so work out His ordering of things that nobody could stand out against Him with respect to it, and He hid the knowledge of that plan from all creatures. Thus the devil did not know it, and still does not, and will forever, until the last day, be ignorant of it. But then, then on the last day, in his great confusion, he will sense some parts of that plan and will know how he will be utterly confounded through it. For the devil thought that mankind was absolutely damned, just as he wished. [2]

This is why so many say we can hope all will be saved, because it is God’s desire that all will be saved. While Satan does everything possible to undermine God’s desire, Jesus, in the incarnation, had done what could be done to overturn all the harm Satan did to creation.

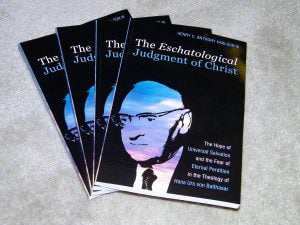

We are no longer bound to sin and so no longer bound to the corruption and annihilation which sin brings to those contaminated by it. This hope, the hope that God’s desire will be fulfilled, is, of course, the hope of Hans Urs von Balthasar,

Some think revelation denies that God’s desire will be fulfilled. They suggest that some will end up among those who are eternally damned. Does not Jesus himself talk about the judgment and those who will be sent to the everlasting fire? However, we must recognize, as the final eschatological judgment has not taken place, the condemnation has not taken place, and might not take place. The story of Jonah, which Jesus took as a sign to represent himself and all that he has done, shows how those once judged and condemned could find that condemnation overturned. Thus, if we use the story of Jonah as a hermeneutic to understand all the warnings of perdition in Scripture, we will be shown such warnings indicate only a possibility, and so not what must happen. Just as in the story of Jonah, so in the eschaton, it is possible to find that God’s condemnation will be overturned by God’s mercy and grace. This is not to say we know that this will happen, only that we do not know what will happen. We have reasons to believe that warnings about hell do not mean anyone will actually suffer eternal perdition. Since we know that God desire all should be saved, we should also recognize, as the apologist Macarius did, that God will not harden people’s hearts so as to make sure they never repent:

But in stating this, the Apostle was not of the opinion that some are granted mercy by God while others are not granted mercy but have their hearts hardened, but rather he hold that all are granted mercy by God and saved, saying: ‘He who wants all men to be saved.” [3]

St. Jerome, despite his conflict with Origen, did not deny the possibility that God has a plan which transcends our imagination and comprehension, one which allows those who suffer in and through their sins to eventually transcend all their sufferings and be saved. While making it clear he was not stating his opinion, he acknowledged that many Christians do think this, that the sufferings or consequences of sin are limited in nature, and so will eventually come to an end:

They reflect upon all these things and long to affirm that after the tortures and torments, there shall be relief in the future. Now, they say, this has to be concealed from those for whom fear is advantageous, so that while they are fearful of punishments, they may stop sinning. [4]

Jerome then acknowledged that various elements of revelation could be used to promote this notion:

On the other hand, those who want the punishments to be ended at some point, even though they grant that this will be after long ages, nevertheless they want the torments to have a limit, and make use of the following testimonies: When the fullness of the Gentiles shall have entered in, then all Israel shall be saved” [Rom 11:25-26]. And again: “God has enclosed all things under sin, that he may have mercy on all” [Rom 11:32; cf Gal 3:22]. [5]

Instead of saying they were wrong, instead of saying that there must be some who will ultimately be lost forever, Jerome indicated that they might be right, that in reality, we do not know what will happen, only God does:

We ought to leave this to the knowledge of God alone. Not only are his mercies in equilibrium, but so are his torments, and he knows whom he ought to judge, how, and for how long. And let us say only what befits human frailty: “O Lord do not rebuke me in your fury, nor chastise me in your wrath” [Ps 6:1]. [6]

Certainly, when one reads through Jerome’s writings, it seems he is far less hopeful that this will be the case than many of his peers. Some of this came out of his fight against Origenism, and the way he understood Origen’s universalism. Nonetheless, he also understood the problem with Origen was the system he created to explain his conclusions. He did not think other arguments which suggested that all could end up being saved had to be condemned. Jerome understood the difference between theological opinion and dogma, and understood that as long as the dogmas of the church were upheld, people could hold a variety of theological opinions. While he certainly would differ with Balthasar and Balthasar’s hope, he would not necessarily see Balthasar as going against church teachings, and indeed, he would welcome Balthasar’s own caveats which, like him, end up reminding us that we do not know what will be in the eschaton until it is revealed to us through our experience of it.

Theological reflection can be and is important. People have questions. They want answers, even if the answers end up only giving us potential solutions to the problems at hand. People want to make sense of all that has been revealed to them. There are many ways this can be done. What is important is that we find something which can sustain us in our faith while recognizing the transcendent mystery of the faith itself, a mystery which cannot be so easily held down and constrained by theological opinions. We must, that is, recognize our limited understanding, our limited awareness of the transcendent truth, and so not try to hold onto and seize it as something which we can control through our reasonings and proofs.

[1] Roger Bacon, Opus Majus. Part II. trans. Robert Belle Burke (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1928), 787..

[2] St. Hildegard of Bingen, “Letter 113r” in The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen. Volume II. Trans. Joseph L Baird and Radd K Ehrman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 56.

[3] Macarius, Apocriticus. Trans. Jeremy M. Schott and Mark J. Edwards (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015), 196.

[4] St. Jerome, Commentary on Isaiah in St Jerome: Commentary on Isaiah; Origen Homilies 1-9 on Isaiah. Trans. Thomas P. Scheck (New York: Paulist Press, 2015), 880.

[5] St. Jerome, Commentary on Isaiah, 880.

[6] St. Jerome, Commentary on Isaiah, 880.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!