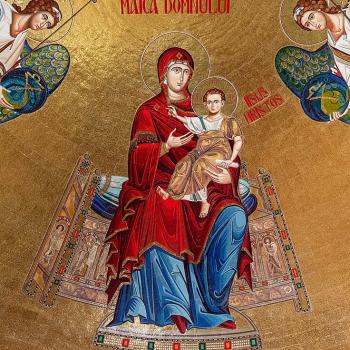

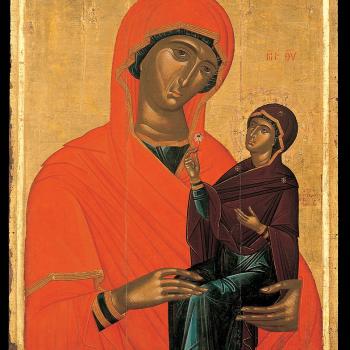

The dormition and assumption of Mary are two parts of one special event in salvation history. The first part, the dormition, refers to her death (as the word, dormition, employs the euphemism Paul used to represent death, that is, sleep, cf. 1. Thes. 4:13-15). Her death led directly to the second part of the event, that is, her entry into eternity, done in a special way, as she was fully assumed into heaven, body and soul, so that she could partake of the glory of the resurrection in anticipation of the rest of us. “She was earth by her mortality and she went into the earth by her death.” [1] She died, not because she was a sinner, but because she was human, one who lived in the world and possessed, through her humanity, a temporal life. She died, and was buried, but, like her son, it is said that her body did not remain in the tomb, which is how Christians came to realize that her body had been assumed into heaven. And yet, though she was glorified, she remained connected with the rest of creation, for her body, even though it was spiritualized thanks to the glorification she received in her assumption, was still connected to the creation from which it came, for it still was a part of that creation, which meant, she still possessed within herself a connection to the world from which she came. Her assumption did not make her abandon the world, but rather, gave her a new way to engage it:

There is no one closer to man, more kindred to the human being than the Mother of God in the heavens. She covers the world [with her mantle], intercedes for it. She is with all creation, over all nature, She is over the waters and the dray lands, the fields and the forests, over humans and creation. She embraces all things in Herself, unites all things – She is a merciful heart to all. After praying to the Lord and while praying to the Lord, pray also to His Mother, the Bearer of the Holy Spirit. Believe that the Mother of God will have mercy and will send you the gift of the Holy Spirit, and you will behold the Son of God living within you.[2]

We shall all die. It is a part of the human condition, a condition which Mary, the Theotokos, shared with us. But it is important to remember, Christ confirmed to us that death is not the end. This is exemplified through Mary. Her assumption, her glorification in heaven, shows us that the resurrection was not just something which belonged to Christ alone. Likewise, as death is not the end, our connection with the rest of creation does not end with our death. Indeed, we must remember, eternity transcends time in a way in which it also contains time within itself, so that what takes place in eternity, eternal life, can and should have an effect on what happens in time. The assumption of Mary, which had her go from temporal to eternal existence, therefore allows her to continue to have influence over what happens in time, even as she continues to experience world history, and all that happens within it, within her new, eternal perspective; she experiences sorrow for the pain and suffering in the world even as she rejoices for all the good, all the grace, shared throughout creation.

The assumption of Mary, of course, connects with the incarnation; for it was in and through her, in and through her flesh, that the Word became flesh. That is because the Word assumed human nature through her, taking from her, from her flesh and blood, transforming what he took so that it became his own. In this way the assumption of Mary, after her death, can be seen as the final act, and indeed, the consequence of the way the Word incarnated through her. “The assumption of our nature was to be also its liberation. And that no one should perchance suppose that the creator of sex despised sex, he became a man born of a woman.”[3] As the assumption of our flesh was through Mary, so the assumption of her flesh was first for her own liberation, and then in and through her, it served for the liberation of the whole of humanity, indeed, the whole of creation. The assumption or glorification of Mary after her death vouchsafes this, showing us that indeed, though Jesus is the first born of the dead, the first to experience the full transformation of the resurrection, he is not the only one. Now, we must not confuse the resurrection as mere resuscitation; rather, it is brings Jesus not only back from the dead, but into a new made of existence, one where the restriction of material creation no longer applies, as his body became spiritualized. Thus, when we are resurrected, we will see how Jesus has liberated us, for we will find ourselves likewise no longer limited to the constraints of pure materiality.

Mary died, not because of any sin she did, but because of her humanity; she was a temporal being. For her to be assumed into heaven, she would have to have her temporal life come to an end. We are told she willingly embraced that death, recognizing that if her son, Jesus, could face death, then she could too. She had experienced the pains and sorrows of death already, as she experienced them through the death of Jesus; and though she was glorified in her death, she still felt the pains and sorrows of death by the way she was connected with the rest of humanity, and with it, human history:

She is in heaven, the glorified Queen of Heaven, but She is also a creature, undivided from the world: She lives its life and is wounded by it and grieves for it and will heal the world in the fullness of time. [4]

Mary truly died, but that was not the end of the story. We, too, shall die, but it shall not be the end of our story either. The resurrection of Jesus has liberated us, making sure that death is truly not the end; rather, it will be when our story truly begins.

[1] Richard of St Victor, “On Emmanuel,” in Interpretation of Scripture: Practice. Trans. Frans van Liere. Ed. Frans van Leiere and Franklin T. Harkins (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2015), 431. [About the Theotokos].

[2] Sergius Bulgakov. Spiritual Biography. Trans. Mark Roosien and Roberto J. De La Noval (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2022), 68-9. [16/29. VIII.1924].

[3] St. Augustine, “Of True Religion,” in Augustine: Earlier Writings. trans. John H.S. Burleigh (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1953), 239.

[4] Sergius Bulgakov. Spiritual Biography, 72 [6/19.IX.1924].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!