The truth is good. This is why the knowing and willing violation of the truth is said to be “intrinsically evil.” Those who willingly seek to deceive others, that is, those who knowingly state some falsehood, or encourage others to believe it, without being forced to do so by someone else, are culpable for their lie. If someone were forced to make a statement under torture, one which they do not agree with and believe to be false, they cannot be said to desire to deceive anyone, and so they are not to be held culpable for what they say. This is not to say, objectively, no evil had been committed, for certainly, some evil had been done; the one who is culpable for it is not the one who was compelled to act contrary to their own desire, but the one who did the compulsion.[1]

Not every lie is equal. The gravity of the evil involved depends upon many factors. Many lies are slight, and so the evil done is also slight. Other lies, however, are far more grave, because they are used to promote and engage some great evil, such as if someone were to lie in order to have some innocent person unjustly harmed or killed.

We should seek to preserve the truth by speaking of it the best we can, “Not deceiving but remaining sincere to all living beings.” [2] Moreover, we should make sure how we speak the truth is such that we speak the truth in love (cf. Eph. 4:25), and not in a matter of fact way that ignores the impact our words might have upon those around us. If we ignore the role love should have in our speech, then our speech is not as good as it should, and insofar as we act contrary to such good, we act contrary to the truth itself, leading us to realize that a factually correct statement said in a cruel fashion, without love, represent some kind of falsehood. “So one who pursues this truth and that truth, separated from the highest truth, without doubt does not light upon truth but upon falsehood.” [3] When we willingly ignore love and disassociate it from our engagement of the truth, we have embraced the partial good over the fullness of the good, and so the partial truth over the fullness of the truth. This is why many who proclaim they only speak the truth, but ignore how they should speak it, are often far from the truth itself, offering only a perversion of it.

Christians have been told that they should worship God with love, showing the relationship love has with the truth. “God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth” (Jn. 4:24 RSV). They should love all that is good, which means, they should love the truth, realizing that such a love for the truth can only be had if they embrace the truth in love. They should be open to and seek after greater and greater truths, allowing themselves to be corrected when they have been mistaken. They should, likewise, desire to share with others the truth they have come to recognize while accepting the fact that they must not unjustly impose their understanding upon others. For, as Solovyov said, based upon his own pursuit of the truth, the truth is not recognized by such compulsion, but by one’s encounter with it:

And as for paths, only honest experience can show which of them is true and which is mistaken. I am always ready to reject directly and decisively any opinion of mine as soon as its falsehood is disclosed in actual fact. Prohibition is not disclosing, and force is not evidence of truth. [4]

To be sure, this does not mean we should embrace anarchy, allowing everyone to be free to do whatever they want to do based upon their own understanding of the truth. What must be embraced is the common good, and with it, a love for each other, a love which seeks the good for everyone; if someone’s “truth” would have them unjustly impose themselves and harm others, they can and should be stopped, though of course, stopping them does not prove them to be in error (although, to be sure, their lack of demonstrates that somewhere, they certainly have strayed from the fullness of the truth).

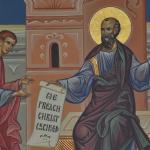

For Christians, Christ is the truth, the truth which is just, and so the truth which is love. This is why those who conform themselves to the truth of Christ will conform themselves to the truth of justice found in the realization of love; they will show forth that love in what they do, making their speech and actions radiate with the truth they have come to know through their relationship with Christ:

The Lord Jesus Christ is justice. No one who acts unjustly is subordinate to Christ, justice. The Lord Christ is truth. No one is subordinate to Christ, the truth, who lies or holds false teaching. The Lord Christ is sanctification. No one is subordinate to Christ, sanctification, when he himself is profane and defiled. The Lord Christ is peace. No one is subordinate to Christ who is hostile or bellicose, unable to say, “I was peaceful with those who hate peace.” [5]

The love for truth, must, therefore, recognize that the truth itself is one with love, for God is the ultimate truth and God is love. “The truth is that by nature every appetite chooses and pursues the good, while it shuns and drives away evil.” [6] Indeed, the truth is so grounded upon love, that love more than various facts serves as the basis of truth. This is why, those who are mistaken about facts can still embrace the truth while those who do not embrace love have already lost the truth. To willfully lie, to counter the truth, requires one to reject such love, while those who speak and act out of love, show they are embracing the truth by their embrace of love. If we want to stand for the truth, if we want to worship God in spirit and truth, we must therefore embrace love; if we don’t, we will find ourselves standing far from the truth, and if we claim to love it and embrace it, all we do is lie to ourselves.

[1] Obviously, we can recognize heroic levels of virtue which are not expected for everyone to follow. Thus, if someone, even under compulsion, did not act contrary to their will, but rather suffered or was killed for what they would not do, they might be seen as acting with heroic virtue if the reason why they didn’t act was for the sake of some greater good. Because these are exceptional cases, and are not to be expected from everyone, we marvel when we hear of such situations. Nonetheless, the point that has been made, that one is only culpable for lying if one wills to deceive, is important because it can open us up to understand difficult moral situations. Not all compulsion necessarily is of the same kind. The compulsion one can be engaging is the protection of some innocent person, so that a person might feel compelled to lie because they want to protect someone else from the one who unjustly questions them. This might be the way we should approach the question of what someone should have done if they were approached by a Nazi officer who asked them if they knew where any Jews were being hid. Knowing that Nazi officer would have the Jews killed if their hiding place was uncovered, the person can be said to be compelled to make a response when they would normally be silent, and so, being forced to speak, they are not culpable for what they say if they act in accordance to what they think the greater good entails in such a situation. The person who was put in such a situation might be said to be justified for saying something which was not factually correct, and the culpability of their words, if it is to be placed upon anyone, would be upon the officer who put them in that situation. This shows that the lie is still a problem, still an evil, but the one who is guilty of it is not necessarily the one who spoke it, but the one who put them in such a situation that they had to speak because whatever they said, some evil would come about as a result. The fact that protecting such an innocent life is the greater good of the two, and so is what is willed by the one who lies, also verifies this.

[2] Tsong-kha-pa, The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. Volume Two. Trans. Lamrin Chenmo Translation Committee. Ed. Joshua W.C. Cutler and Guy Newland (Ithaca: NY: Snow Lion Publications, 2004), 79.

[3] Marsilio Ficino, The Letters of Marsilio Ficino. Volume 4 (Liber v). trans. by members of the Language Department of the School of Economic Science, London (London: Shepheard-Walwyn, 1988), 23 [Letter 15: To Angelo Manetti].

[4] Vladimir Soloviev, The Karamazov Correspondence. Letters of Vladimir S. Soloviev. Trans. and ed. Vladimir Wozniuk (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2019), 162 [Letter to Tertii Filippov, July 30, 1889].

[5] Origen, Homilies on the Psalms: Codex Monacensis Graecus 314. Trans. Joseph W. Trigg (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2020), 90 [Homily 2 on Psalm 36].

[6] Marsilio Ficino, The Letters of Marsilio Ficino. Volume 4 (Liber V), 49 [Letter 34 to Cardinal Raffaele Riario and Francesco Salviati].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!