Jesus taught the public through stories. “With many such parables he spoke the word to them, as they were able to hear it; he did not speak to them without a parable, but privately to his own disciples he explained everything” (Mk. 4:33-34 RSV). Through stories, we can express our hopes and fears, our thoughts and desires, and work through all kinds of speculations and ideas which we have in our minds. While stories are written and shared, in part, to entertain (and, for many of them, that is their primary purpose), this doesn’t mean that they have nothing to teach us. Indeed, stories, even those meant for entertainment, teach us much about the human condition, for they rely upon the human condition to be told. There are all kinds of concepts, all kinds of givens, used in any story to generate the tale, and those concepts, fictional or not, speculative or not, impossible or not, provide us not only entertainment, but things for us to consider once we are done with the story.

When engaging stories, contemplating what is happening in them, we end considering all kinds of notions which we might not otherwise have considered, and in doing so, learn all kinds of new ideas. Even if we know the story is fictional, and much of what is done in it is impossible, we still discern in them various aspects of the human condition, for they show us how humanity could and would react if it had to deal with such situations. And, sometimes, what was once considered impossible, becomes possible, and such stories prove to be prophetic, helping prepare us for the future. Similarly, stories often reflect metaphysical principles in ways which seem grand or fantastic, but in doing so, they only present to us traces of the transcendent reality which lies beyond the fiction of our own historical narratives. Myths, for example, present elements of the transcendent truth in ways simple empirical narratives cannot do, and in this fashion, they often appear fantastic because they deal with non-empirical truths, and because they are not simple empirical narratives, we must not try to read them as histories if we are to understand them, even if they contain elements of history in them (which is why the book of Genesis, with its creation myth, must not be understood as simple history, for it is a myth, not a historical text). Myth, therefore, is often the best kind of story to use if we want to get beyond the limitations of pure empiricism, as Bulgakov noted:

Therefore the language of empirical history cannot be used to represent meta-historical events. The language of symbols or “myths” is the appropriate one. These symbols derive from mythologemas that are stored in the memory of humankind as an echo of anamnesis of prehistoric or meta-historic events. A myth, in the positive sense of this concept, is a story, expressed in a language not proper to the empirical domain, about what lies beyond this domain, about what belongs to the meta-empirical domain and meta-history. [1]

Hopefully, this will help us understand why fantastic fiction, in all its forms, can provide us comfort, not just because they entertain us, but they act as mini-apocalypses, revealing something about the inner nature of reality, the nature of reality which the author of the tale has, in one fashion or another, experienced for themselves (however exaggerated or developed it becomes in the telling of the tale).

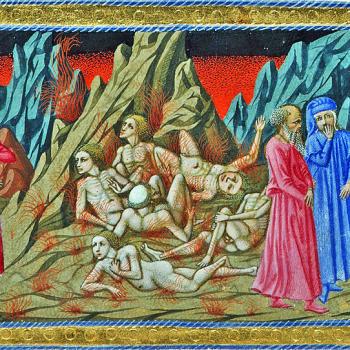

Horror stories remind us, for example, of the demons around us, especially the demons of our own creation, though they can also show us the dark spiritual principles or demons which try to consume or destroy that which is good. That is, we are warned through them of the horror which lies all around us, the horror which we must face and overcome; we see in them that we can lose our fight to them, as many killed in such stories, but usually, there are those who remain to the end and overcome the evil they face, showing us that there can be victory over evil as the goodness of creation, and the goodness within us, can often holds its own against the evil which tries to destroy it. Good, in other words, is shown to survive, in some form or another, meaning good in and of itself transcends the power of evil, though we are also warned, we often face many such horrors in our life, as those who are victorious one day might have to face another demon, another horror the next day (which, sometimes is a repetition of the one we just faced and overcame, which explains why horror stories can become horror series, where one type of horror constantly returns). However, we also see in such stories, the charm and beauty which evil can have, as evil is never purely evil, pure monstrosity, but rather, it has a beauty of its own, a goodness which it uses and abuses to engage its onslaught against nature. This is why, as S.L. Frank surmised, beauty can be said to save the world, but not all beauty will, as some beauty can be said to be an evil beauty (which, of course, many horror stories demonstrate by showing how charming and seductive even the greatest of monsters can be):

Beauty as such does not save him from the destructive forces of evil or from the tragic nature of human life. Beauty as such is neutral. In a sense it is indifferent to good and evil. Symbolizing some potential harmony of being, it peacefully co-exists with actual disharmony. Furthermore, according to Dostoevsky’s profound insight, beauty combines itself in the “divine” and the “demonic,” for wherever we are seduced by deceitful appearances, there we have dealing with the demonic. This lack of concord between beauty – esthetic harmony – and the genuine reconciling, redeeming essential harmony of being was manifested concretely with astonishing persuasive force in the tragic life-experiences of such artists as Botticelli, Gogol, and Tolstoy. We can say that beauty is a sign of the potential harmony of being, of the possibility of actual, fully realized harmony. And if the world were perfectly beautiful, it would be perfectly harmonious, in inner accord, free of tragic duality. Therefore the dream of the ultimate transfiguration of the world is a dream of the complete triumph of beauty in the world. But it is precisely only a dream, which is opposed by the bitter reality of the inner discord and duality of being. Beauty is only a reflection of “paradise,” of the ontological rootedness of all reality in divine total unity.[2]

Evil, then, must be revealed for all it is, and horror stories can and should help us with that unveiling. Through them, we can find many of our ideas about evil are mistaken, even as we can find many of them are affirmed. We can seee in them the dangers which evil present to the world, but also the way the world can and does endure all the horrors given to it. We learn that there is psychological horror, where we risk becoming a monster ourselves, even as there is a cosmic horror, where the greatness of being itself is being attacked by the chaotic abyss. Moreover, there is also religious horror, where religion can be both a force for good as it is used to confront and overcome some particular horror, but it can also be a force for evil itself, as the pretense of holiness can create its own monsters. “For immoderate abstinence breeds in an arrogant boastfulness, which has no foundation; and, besides, it produces many terrors, which appear to be holy, but are not.”[3]

Horror stories should not to be dismissed because they deal with and reflect upon evil, as if they are themselves that evil. Rather, horror as a genre should be seen as an apocalyptic genre, one which not only shows what we are facing, but also gives up hope in all the terror, as they can show ways in which the light of goodness can and will resist evil. To be sure, sometimes, the victory of the good will merely be shown in the way it endures and finds a way to prevent itself from being snuffed out by some monstrous evil. But that is still a victory, and one which allows for other, further victories. Once any particular victory has occurred, healing then can take place. Thus, horror stories, far from supporting and promoting evil, actually help us see the limit of evil, the limit of even the most dark and dangerous evil, showing that in the end, evil can be overcome, and that all such evil, even the most powerful can, has its power, not from itself, but from distortion of what is good and beautiful. That revelation can and will then help us understand, in the eschatological sense, how evil is overcome by the incarnation. The story of the incarnation is, in its way, the ultimate horror story, as the God-man is killed and suffers the pains and sorrows, indeed, the horrors of the dead only to show that such horror can and will come to an end by the revelation of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. In the story of the God-man, we are shown that all the horrors found around us, all the demons and powers of darkness, will lead to their own doing. When they were at their greatest power, they led Jesus to the cross, and had him executed, and in the process, exhausted all their power, so that their apparent victory became their defeat, death overcame death, and what came forth was a good which would no longer suffer under their nihilistic hatred.

[1] Sergius Bulgakov, Bride of the Lamb. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 170.

[2] S. L. Frank, The Unknowable: An Ontological Introduction To The Philosophy of Religion. Trans. Boris Jakim (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2020), 196.

[3] St. Hildegard of Bingen, “Letter 234” in The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen. Volume III. Trans. Joseph L Baird and Radd K Ehrman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 33.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!